How Brexit hit the pound in your pocket

- Published

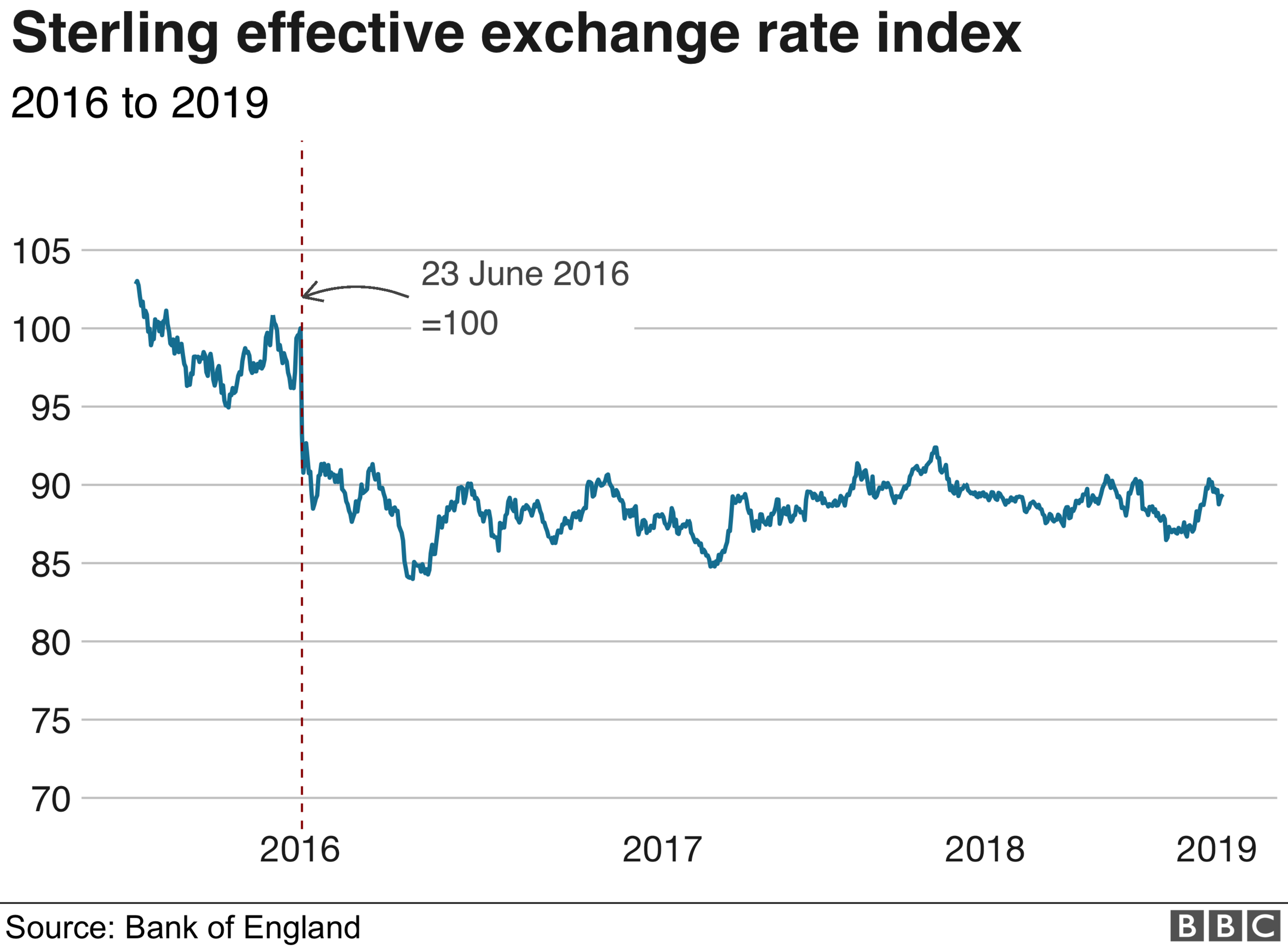

The value of the pound has changed a lot over the past three years - making us all a little poorer.

Back in December 2015, £1 would buy you about €1.40.

Today it will get you nearer €1.14. It has suffered a similar fate against most major currencies, losing about 15% of its value over that time.

A big part of the fall occurred literally overnight, once the result of the EU referendum became apparent in the early hours of 24 June 2016.

That's a big change, but what does it mean for all of us?

It hits home immediately if you go on holiday. A €100 meal in a Spanish restaurant would have set you back about £70 three years ago, but would now cost almost £90.

And that ignores the cost of changing your money. You can easily get less than €1 for your pound if you exchange at the wrong place.

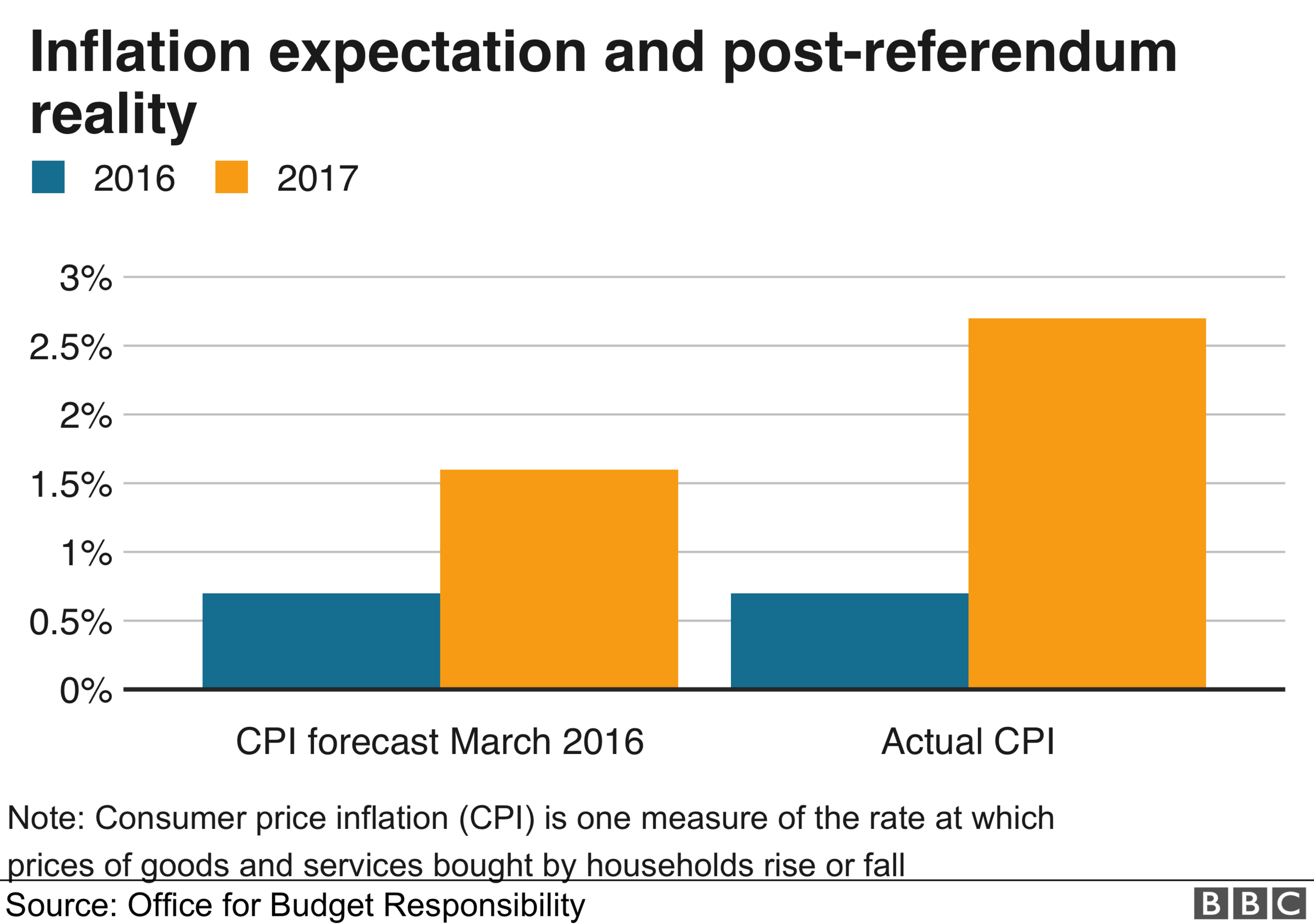

More importantly, the fall in the pound has also increased the price of things in the shops at home.

That is because a lot of what we buy is imported and is especially true of food and fuel, but much else besides.

And because the pound is worth less, we need more of them to pay for Spanish oranges, German cars or French wine.

Most analysis suggests that prices are now at least 2% higher than they would have been if the pound had not fallen in 2016. That leaves most of us worse off.

It is probably not right to say, though, that we are worse off because the pound fell in value.

It fell for a reason. It fell because people and companies deciding where to keep their money took the view that the UK had become less attractive.

That is because political uncertainty increased and many believed trade with the EU, our biggest, richest and closest trading partner, would be made more expensive.

So the falling pound reflects our diminished state rather than causing it.

In a sense, a falling pound acts as something of a safety valve. It makes our exports cheaper abroad, helping to cushion the impact of leaving the EU.

Some people have suggested that a weaker pound is actually a good thing. They say this will help our economy in the long run as it could make our goods more competitive abroad.

So far they have been disappointed. There has not been an export boom.

Nor is there evidence of a reduced dependence on foreign imports.

Rather, both exports and imports have continued to potter along much as they did before the referendum.

That is not to say it won't help our exports in the long run.

It can take a long time for firms to adjust, to find new markets and to increase exports. But there has been no big effect so far.

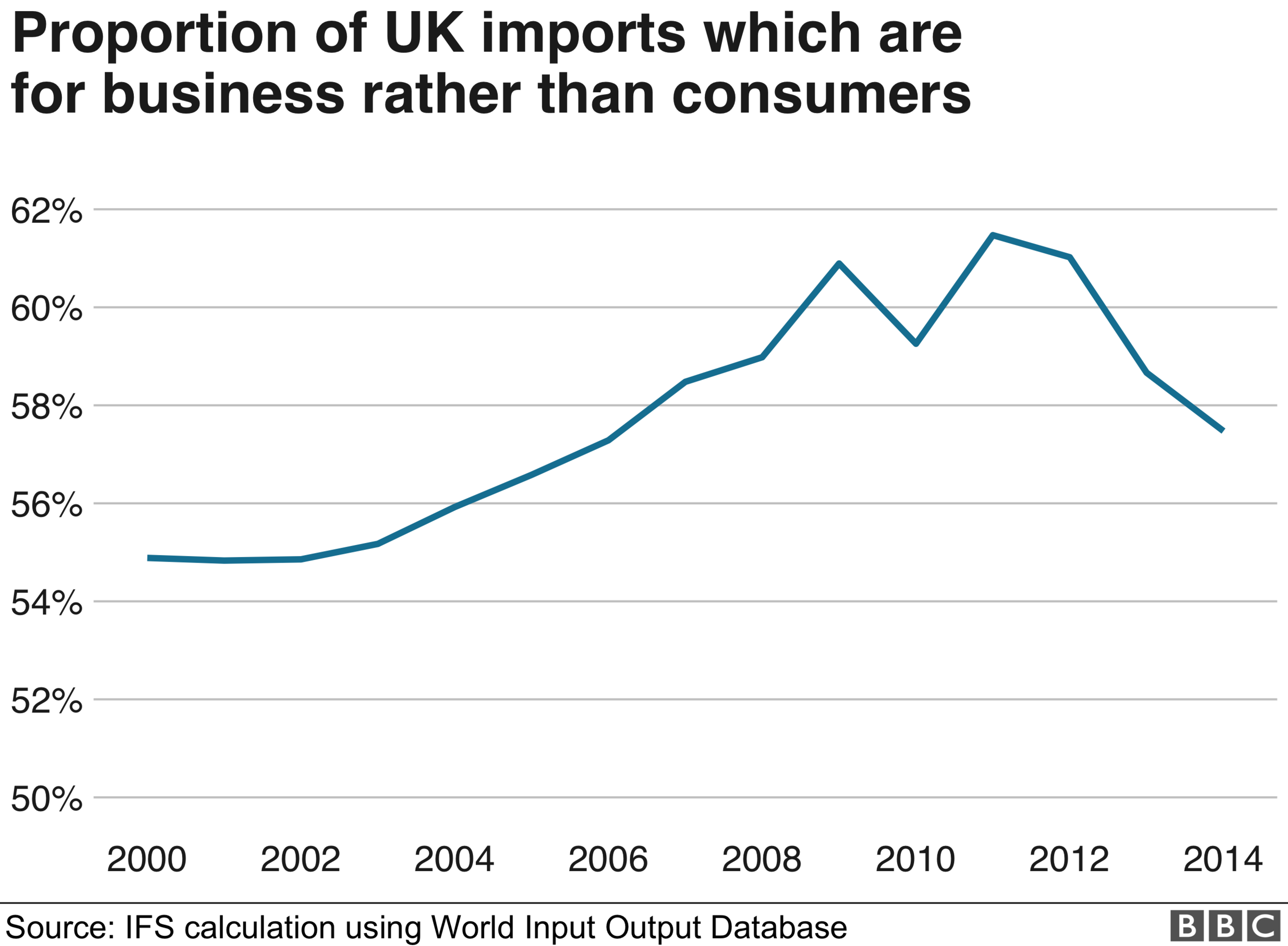

It is not just consumers who can lose from a falling pound. It can be bad for businesses too.

An important fact about international trade is that most of it is between businesses, rather than straight from business to consumers.

This affects UK businesses dependent on importing raw materials, components (like engines for cars) or services to make their own products. They face higher costs when the pound depreciates.

This globalisation of firms' supply chains is one reason why the weaker pound has done less to make UK exports competitive than in the past.

Find out more

Paul Johnson's Analysis programme, Fair Exchange, will be broadcast on BBC Radio 4 at 21:30 GMT on Sunday 24 February and can be listened to here.

However, one group of businesses that may have benefitted are those dependent on foreign tourists. While it is more expensive for Britons to go on holiday abroad, it is cheaper for foreigners to come here - a benefit which is passed on to the shops and restaurants where they spend their money.

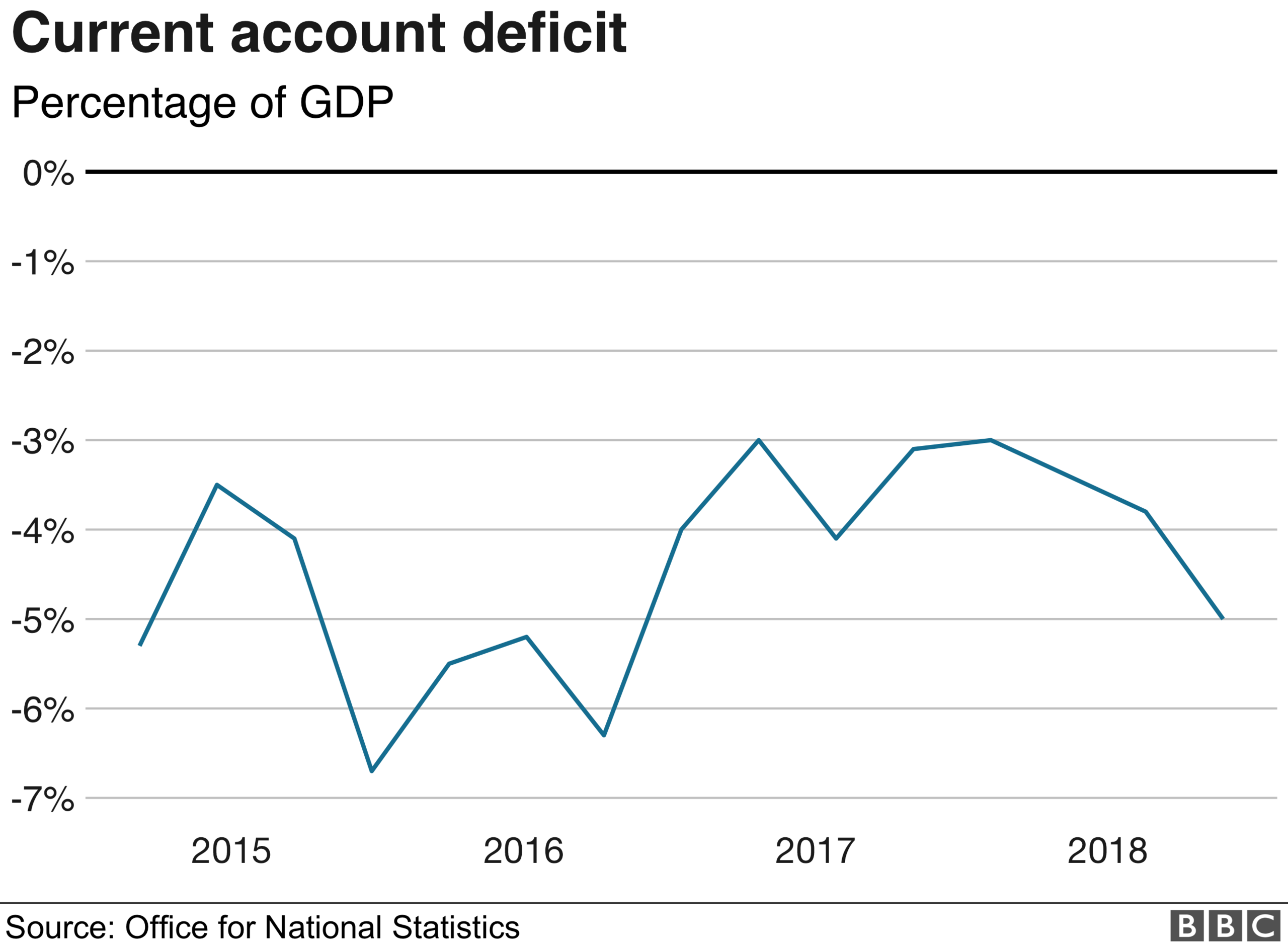

Finally, one thing that often puzzles people is the fact that for decades we have bought more from other countries than they buy from us. How can that be?

The answer is that this trade deficit is matched by a surplus elsewhere.

Essentially foreigners are willing to lend us money - or buy our assets - because they believe the UK is a pretty safe, stable and open economy.

As a result, we are able to consume more than we produce.

In fact some have argued that we have been too attractive for foreign money - too stable, open and trustworthy. The result, they say, is that this foreign cash has pushed up the exchange rate, making UK businesses less competitive.

We will see where this all takes us.

The fall in the pound has made the UK less attractive to foreign investment. This has made not just our holidays, but our weekly shop more expensive.

If there are any benefits to this, we have not seen them yet.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Paul Johnson is director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, external and Peter Levell, external is one of its senior research economists.

More details about the work of the IFS can be found here., external

Edited by Duncan Walker

- Published4 December 2018

- Published2 February 2017