Would a 'digital you' make buying clothes online easier?

- Published

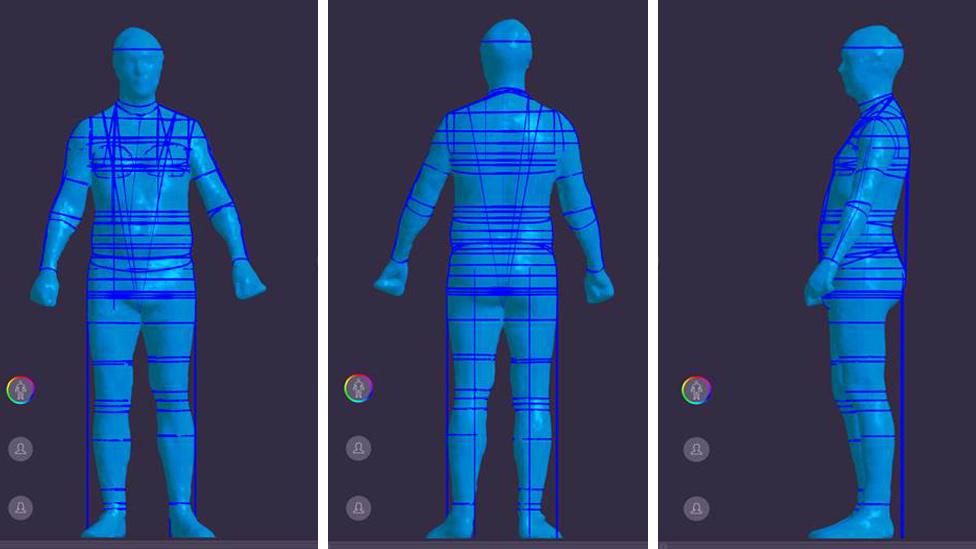

Metail's body scanner takes your detailed measurements to create a digital avatar

It was with some trepidation that I stripped down to my underwear and stepped into the booth.

The Size-Stream Scanner, as it's known, is currently just a prototype and is merely a space with a curtain pulled around it, fitted with 10 sensors, all trained on different parts of me. The music starts up, I place my feet on the marked spot, and grab a pair of handles.

Within seconds the machine has my precise dimensions after taking three scans of my body. On a screen outside I get to see myself modelled in 3D.

"We get to construct a body model of you, with all the lumps and bumps, so it's very personalised," explains Jim Downing, the chief technical officer of Metail, the Cambridge company that's developing this new tech.

You can say that again.

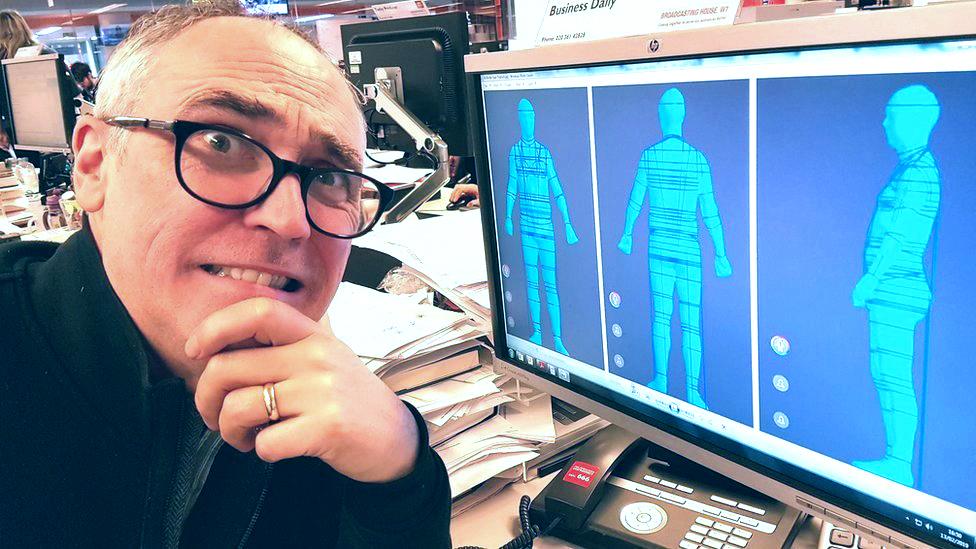

I look at myself aghast, silently concluding that my slightly fitful New Year diet regime clearly needs stepping up.

Ed Butler is less than impressed with his unflattering body scan

The idea is that you can then dress the virtual model of yourself in various outfits online and see how they look from all angles. The retailer can also send you fashion ideas as new designs come in, as modelled by your digital avatar.

"Everybody has the ability to look great," says Metail founder Tom Adeyoola. "There's no reason why we won't move to a future where the idea of size disappears. It's about dressing the best for your shape to make you feel good."

But I'm told the slow take-up of this kind of tech in Western clothing outlets is partly because retailers are concerned that customers - like me - may be put off by what they see.

"If people want the most accurate way of capturing their body shape this is a great way of doing it," says Mr Adeyoola.

"But we want the easiest way, so we also built a statistical model. For a woman, if you enter height, weight and bra size, plus your general shape - hour-glass or pear-shaped - you can get a sense of what your fit will be that's 92% to 96% accurate."

But he reckons that in time both of these methods will be overtaken by the mobile phone, which will become "an exceptionally good and accurate tape measure".

One company with similar ideas is Japanese online fashion retailer Zozo.

WATCH: How well does Zozosuit measure up?

It sends customers a figure-hugging body stocking featuring unique positioning spots all over it. You squeeze into the bodysuit, stand in front of your mobile phone and turn 360 degrees while the phone takes snaps of you to create a 3D model of your shape.

You can then order "custom fit" clothes from a currently limited range.

It's an interesting idea, but when my colleagues on our Technology desk tried out the Zozosuit, they found that it didn't work so well.

And this is the big challenge for online fashion retailers. Shoppers love the convenience but they can't try the clothes on first, so returns are high, and this adds a layer of cost which is often passed on to customers.

Achim Berg, co-author of the McKinsey consultancy's annual State of Fashion report, says: "Women don't like to buy jeans in stores and it's not any better at home." They are likely to return them 70% to 80% of the time, he says.

In Germany, where there is a long history of mail order shopping, return rates are about 50%, says Mr Berg, whereas the figure is somewhat lower in the UK.

Amazon's "try before you buy" service is available to its Prime members

"Try before you buy" services offered by the likes of Amazon, Asos, Topshop and JD Sports merely exacerbate the returns issue, although the retailers hope higher sales will offset this cost.

So more online retailers are trying to offer bespoke clothing and personalisation services.

That's borne out by recent moves by Amazon to patent a "virtual fitting room" app. Yet to be developed, the app would scour a customer's social media photographs to predict their fashion style before identifying possible suggestions.

"The number one trend in fashion right now is personalisation," says Julia Bösch from Outfittery in Berlin, one of Europe's largest online retail firms. "We've found that most customers are really overwhelmed with the choice they're provided with, particularly online."

Outfittery founders Julia Bösch (left) and Anna Alex are on a mission to personalise fashion

Outfittery uses algorithms and human stylists to come up with a selection of clothes tailored to your stated style preferences, size, personality and aspirations.

Ms Bösch says the company has 20 algorithms making the selections and eventually it plans to develop its own exclusive brands using the insights it has gleaned from its 600,000 customers.

But if online fashion makes itself even more attractive, does that spell further trouble for physical shops?

"The High Street is struggling to differentiate itself from what's online," says Mr Adeyoola. "We need fewer shops, but these need to become more interesting brand retail experiences."

Nike recently launched a new store in New York where customers can try on sports shoes and immerse themselves in a digital game while running on a treadmill. Alibaba has launched similar "experience-led" stores in China.

McKinsey's Achim Berg concludes: "We believe stores will become smaller. They will become much more a blend of picking up stuff you've ordered online and returning products you didn't like.

"They will be much more service orientated, with less display, and then you're going to have flagship [stores] where brands can really showcase what they can offer."

The virtual fitting room may be too much for some, but it's clear the boundaries between online and offline will continue to blur as we continue our search for the perfect fit.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external