Could hackers 'brainjack' your memories in future?

- Published

Could technologies of the future allow hackers into precious corners of our minds?

Imagine being able to scroll through your memories like an Instagram feed, reliving with vivid details your favourite life moments and backing up the dearest ones.

Now imagine a dystopian version of the same future in which hackers hijack these memories and threaten to erase them if you don't pay a ransom.

It might sound far-fetched, but this scenario could be closer than you think.

Opening up the brain

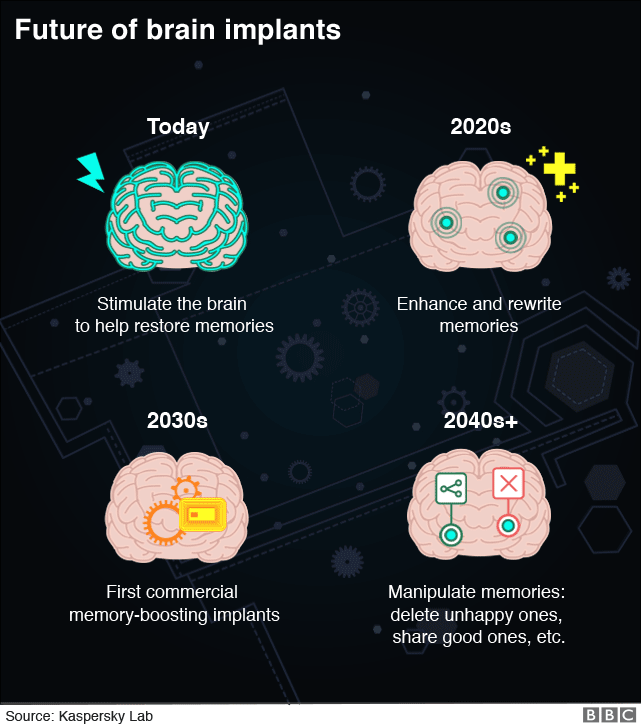

Advances in the field of neurotechnology have brought us closer to boosting and enhancing our memories, and in a few decades we could also be able to manipulate, decode and re-write them.

The technologies likely to underpin these developments are brain implants which are quickly becoming a common tool for neurosurgeons.

They deliver deep brain stimulation (DBS) to treat a wide array of conditions, such as tremors, Parkinson's, and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), in around 150,000 people worldwide. They even show the potential to control diabetes and tackle obesity.

Advances in the field of neurotechnology promise to bring better understanding of our brains

The technology is also increasingly being investigated for treating depression, dementia, Tourette's syndrome and other psychiatric conditions.

And, though still in its early stages, researchers are exploring how to treat memory disorders such as those caused by traumatic events.

The US Defense Advance Research Projects Agency (DARPA) has a programme to develop and test a "wireless, fully implantable neural interface" to help restore memory loss in soldiers affected by traumatic brain injury.

Mental superpowers

"I wouldn't be at all surprised if there is a commercially available memory implant within the next 10 years or so - we are talking about this kind of timeframe," says Laurie Pycroft, a researcher with the Nuffield Department of Surgical Sciences at the University of Oxford.

In 20 years' time, the technology may evolve enough to allow us to capture the signals that build our memories, boost them, and return them to the brain.

By the middle of the century, we may have even more extensive control, with the ability to manipulate memories.

'Brainjacking'

But the consequences of control falling into the wrong hands could be "very grave", says Mr Pycroft.

Imagine a hacker has broken into the neurostimulator of a patient with Parkinson's disease and is tampering with the settings. They could influence his or her thoughts and behaviour, or even cause temporary paralysis.

A hacker could also threaten to erase or overwrite someone's memories if money is not paid to them - perhaps via the dark web.

Hackers could either target high-profile individuals or mass target groups of individuals

If scientists successfully decode the neural signals of our memories, then the scenarios are infinite. Think of the valuable intelligence foreign hackers could collect by breaking into the servers of the Washington DC veterans' hospital, for example.

In a 2012 experiment, researchers from the University of Oxford and University of California, Berkeley managed to figure out information such as bank cards and PIN numbers just by observing the brainwaves of people wearing a popular gaming headset.

Controlling your past

"Brainjacking and malicious memory alteration pose a variety of challenges to security - some quite novel or unique," says Dmitry Galov, a researcher at the cyber-security company Kaspersky Lab.

Kaspersky and University of Oxford researchers have collaborated on a project to map the potential threats and means of attack concerning these emerging technologies.

"Even at today's level of development - which is more advanced than many people realise - there is a clear tension between patient safety and patient security," says their report, The Memory Market: Preparing for a future where cyberthreats target your past.

It is not impossible to imagine future authoritarian governments trying to rewrite history by interfering with people's memories, and even uploading new memories, the report says.

Carson Martinez from the Future of Privacy Forum is sceptical about memory manipulation

"If we accept that this technology will exist, we could be able to change people's behaviour. If they are behaving in a way that we don't want them to, we can stop them by stimulating the part of the brain that sparks bad emotions," Mr Galov tells the BBC.

Carson Martinez, health policy fellow at the Future of Privacy Forum, says: "It is not unimaginable to think that memory-enhancing brain implants may become a reality in the future. Memory modification? That sounds more like speculation than fact."

But she admits: "While the threats of brainjacking may not be imminent, it is important that we consider them and work to prevent their materialisation."

Even the idea of brainjacking "could chill patient trust in medical devices that are connected to a network", she warns.

Unauthorised access

Hacking into connected medical devices is not a new threat. In 2017, US authorities recalled 465,000 pacemakers after considering them vulnerable to cyber-security attacks.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) said ill-intentioned people could tamper with the devices, changing the pace of someone's heartbeat or draining the batteries, with the risk of death in either scenario.

Doctors and IT manufacturers will need to collaborate to stay up-to-date with cyber-security issues, according to Galov and Pycroft

No harm was done, but the FDA said: "As medical devices become increasingly interconnected via the internet, hospital networks, other medical devices, and smartphones, there is an increased risk of exploitation of cyber-security vulnerabilities, some of which could affect how a medical device operates."

This is a problem for many medical areas and Kaspersky believes that, in the future, more devices will be connected and remotely monitored by machine. Doctors will only be called in to take over in situations of emergency.

Cyber defences

Fortunately, reinforcing cyber-security early in the design and planning of the devices can mitigate most of the risks.

"Encryption, identity and access management, patching and updating the security of these devices, will all be vital to keeping these devices secure and maintaining patient trust in them," says Ms Martinez.

Clinicians and patients need to be educated on how to take precautions, thinks Mr Galov - setting strong passwords will be key.

Humans represent "one of the greatest vulnerabilities" because we can't ask doctors to become cyber-security experts, and "any system is only as secure as its weakest part".

Mr Pycroft says that in the future, brain implants will be more complex and more widely used to treat a broader range of conditions.

But he gives a stark warning.

"The confluence of these factors is likely to make it easier and more attractive for attackers to try to interfere with people's implants," he says.

"If we don't develop solutions for that first generation of implants, then the second and third generations will still be insecure - but the implants will be so much more powerful that the attackers will have the advantage."

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external