How does a museum remember a defeat?

- Published

How should the French show their celebrated defeat at Agincourt?

The battle of Agincourt in 1415 was immortalised in Shakespeare's Henry V as a miraculous underdog English victory over the French.

So why is France investing millions of euros to upgrade the museum near the battlefield in the village of Azincourt in northern France?

The new centre will tell the story of the battle, the weaponry deployed and life in medieval France - and the museum's director, Christophe Gilliot, says it will be a big improvement on the existing exhibition.

Perhaps the most striking change is to the statistics used by the centre about the number of troops at the battle.

The site of the battle is near the village now known as Azincourt, in the Pas-de-Calais region

When the old museum opened on the site in 2001, its exhibition boards said 9,000 English soldiers fought 30,000 French at Agincourt.

The new centre, expected to open in the autumn, will reduce these figures to 8,500 English and 12,500 French.

It's still an upset, but a long way from Shakespeare's underdog story of Englishmen outnumbered five to one.

Professional armies

Before diehard fans of Henry V cry foul, Mr Gilliot says the numbers were agreed in consultation with historians from England and France.

They are based on research by Professor Anne Curry of the University of Southampton, who studied financial records at the National Archives in London.

A monument with flags marking the site of the battle fought between French and English armies in 1415

"Both armies were essentially professional, paid troops so we have a lot of financial records on them - we can find out the size of the armies and even the names of a lot of the soldiers," said Prof Curry.

Records show that Henry V took 12,000 men with him when he set out from Southampton and left many of them behind to man the garrison after an earlier victory at the port of Harfleur.

Prof Curry says her findings are respected by medieval historians, but unpopular with some English fans of the Agincourt story.

Chain mail to hate mail

"I've had hate mail and trolling and I've been astonished how seriously people take these things," she said.

Prof Curry thinks this can partly be explained by how Agincourt is seen in England in patriotic terms.

When she attended the 600th anniversary of the battle in 2015, people came draped in St George's flags.

There is a sense of "how we have fended off France in the past", she said.

An illustration of the museum which from the autumn will tell the story of Agincourt

Prof Curry believes Agincourt's myths persist in part because so many people claim to be descended from soldiers who fought there.

Unsurprisingly, her research on the size of the armies has not faced resistance in France.

But regardless of the troop tallies, it still seems surprising that the French national and regional governments are investing so heavily in a lost battle.

'Just history'

But Mr Gilliot says patriotism in France is "different".

"We had the revolution in 1789, and since this period we don't really care whether a battle was lost or won by what we call the 'ancien regime'," he said.

"It is just history."

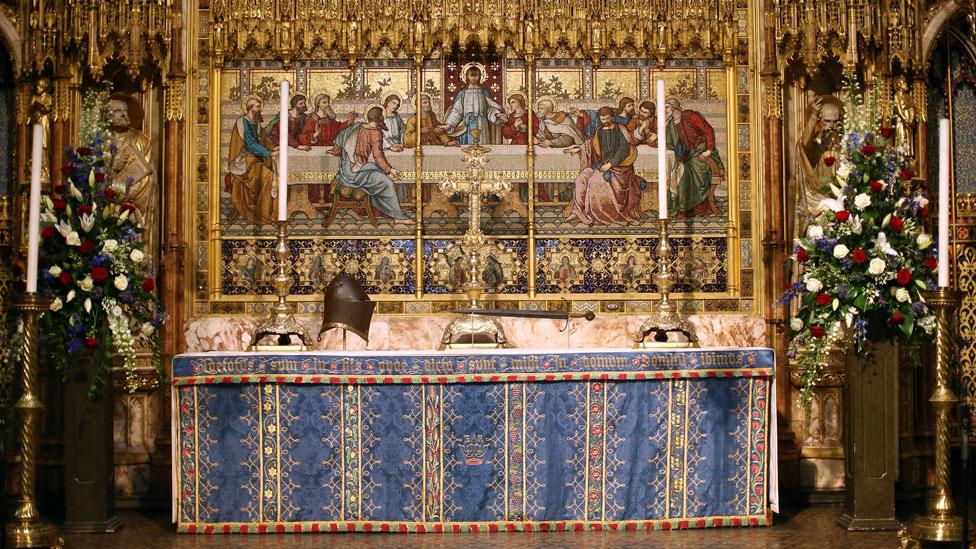

Henry V's helmet was on display at Westminster Abbey in events marking the 600th anniversary of Agincourt

Prof Curry says the French have done a "clever thing" by focusing on the fact that the first member of France's Gendarmerie - which still exists today as a branch of the French armed forces - died at Agincourt.

"At the 600th anniversary, the Gendarmerie were there and people talked about the battle being the origin of their story," she said.

Prof Curry says the revamp of the museum, the "Centre Historique Medieval", is also an attempt to improve the struggling economy of the region of Pas-de-Calais.

"It's very economically deprived, most people just drive through this area on the way to somewhere warmer," she said.

Prof Curry said it was an area where there had been support for the right-wing National Front party, with disquiet about immigration.

Tourist economy

Mr Gilliot says the museum has produced a "parallel economy" for local bed and breakfasts and restaurants, becoming a destination in an area with few tourist attractions.

It seems to be paying off - the English make up the majority of the museum's visitors.

School groups go to the current museum marking the medieval battle

Mr Gilliot says the level of knowledge of this historical period differs between French and English visitors.

"We are very surprised that a lot of English people know their national history very well and sometimes we have visitors who are descended from a nobleman who participated in the battle," he said.

"English people want to know where the castle was that Shakespeare describes in his play, or to visit the battlefield."

"For the French visitors, the questions are very different, they often ask who won the Hundred Years War.

"We are seeing that the Medieval period is not really covered in schools in France."

'No boasting'

But he has never met English visitors boasting about the result.

"Our English visitors are very respectful, interested and well-educated, and they sometimes help us by pointing out problems in our translations," he said.

Henry V became an icon of victory against the odds: Sam Marks of the Royal Shakespeare Company portrays the king

With Brexit looming, Mr Gilliot says the new centre could play a positive role in future Anglo-French relations when it opens in the autumn.

"In this period of Brexit, the museum in Azincourt is very important to understand why our two countries are friends," he said.

"There is a link between the Agincourt and Somme battlefields, because it helps us understand how we came from enemies to friends," said the museum director.

"The centre will be a good place to understand where national identities come from and to understand that it is important to have an identity.

"But it also reminds us that sometimes, when the feeling of identity is too strong in different countries, it leads to war."

More from Global education

The editor of Global education is Sean Coughlan (sean.coughlan@bbc.co.uk).