Why is the white hot Chinese tech sector cooling down?

- Published

Food for thought: tech entrepreneur Lin Liu believes "winter is coming" for tech firms

China's once scorching tech sector is cooling off.

"Winter is coming," laughs Lin Liu, a 29-year-old Shanghai tech worker.

Electric vehicles, industrial robots, and microchip production all slowed recently.

Big firms like Alibaba, Tencent, and search engine Baidu have slashed jobs.

Overall, one in five Chinese tech companies plans to cut recruitment, says jobs site Liepin.com.

"And I think this slowing down will continue," says Ms Liu, who's run a tech start-up and the Slush start-up conferences in Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Nanjing.

China's rate of economic growth is slowing as markets become saturated

The US-China trade war is partly why - both nations imposed tariffs on each other's goods in 2018.

But China's economy, which has enjoyed double-digit growth in six of the last 15 years, will slow to 6.3% growth in 2019, predicts the International Monetary Fund.

This is still double the world's average, but China's slowest growth since 1990.

And China's start-up scene, boasting a third of the world's "unicorns" - start-ups worth more than $1bn (£769m) - is plotting a "strategic restructuring" as the economy and tech sector cool, Ms Liu says.

"What drove things completely insane was too much money," argues William Bao Bean, managing director of Chinaccelerator, a Shanghai-based start-up accelerator.

Chinaccelerator's William Bao Bean says too much money was sloshing around the tech sector

There was a "real push for economic growth from the government" and big funding from state coffers, he says.

This has levelled off.

"Before, you could get $3m with two people knocking and a smile. Now you can get $3m with two people knocking and a smile and six weeks of meetings," he says.

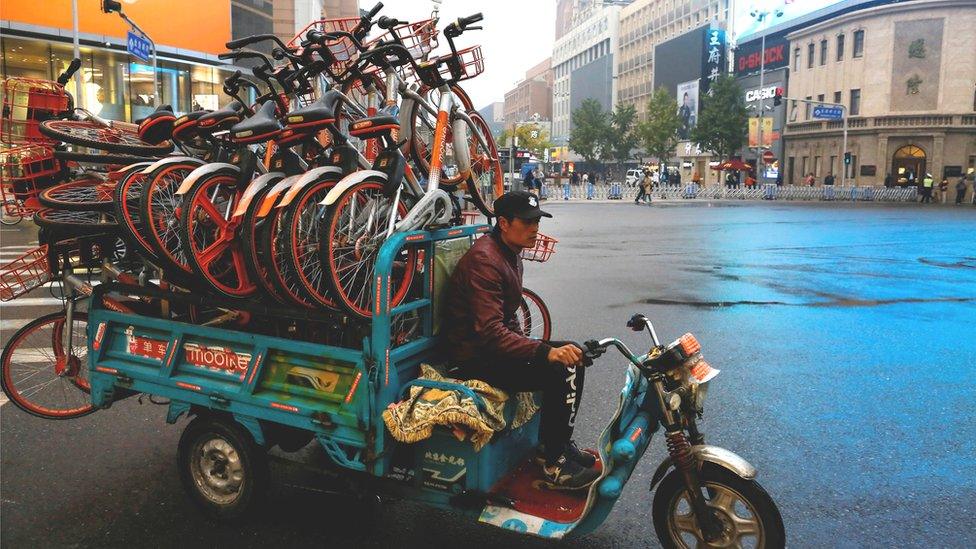

Dockless bike sharing rivals Mobike and Ofo were pedalling off with investors' money last year in a bitter duel for market share.

That sector's now hit the brakes.

"You definitely have a lot more people walking around those bikes than riding those bikes," says Gregory Prudhommeaux, who has worked with Shanghai start-ups since moving from France in 2005.

Mobike's bicycle-sharing scheme lost hundreds of millions of dollars last year

Ofo owes one billion yuan ($148m; £114m) in unpaid debts.

In December, a Beijing court placed it and chief executive Dai Wei on a blacklist after Ofo defaulted on suppliers' payments.

And Mobike lost 4.6 billion yuan in 2018 and won't make a profit until 2021, says China Tonghai Securities, a Hong Kong broker.

It quietly doubled its Beijing fees last month, with one yuan now buying you a 15-minute ride instead of half an hour.

China's 6,200 online peer-to-peer lending platforms, like Weida and Yirendai, were a thriving bubble two years ago.

But 80% have closed or hit major difficulties since, says the Yingcan Group, a Shanghai consultancy.

Amid a government crackdown, this number might dip below 300 by the year's end.

China start-up adviser Gregory Prudhommeaux says tech firms are reining in their spending

Belt tightening has been one result, as companies shed "the coffee machine in the office and the subsidised taxi ride home after 9pm", says Michael Norris, a Shanghai-based Australian who researches China's tech scene.

"The bar and restaurant scene is slowing down, people are eating out less on expenses," agrees Mr Prudhommeaux.

Tech companies are also pushing employees harder, resulting in rising complaints about the common "996" working week - 9am to 9 pm, six days a week.

For companies, "the feeling at the top end of town is that the easy growth is gone," says Mr Norris.

One reason is that China's market is more saturated.

While only 56% of the population is on the internet, Tencent, Shenzhen's internet giant that last year became Asia's first $500bn-plus company, says this percentage includes most of the people who buy online.

"When you account for those who are too young or old to own a smartphone, and people who have a little bit of money, we're basically at saturation," Mr Norris says.

So it's pricier to get customers.

This means start-ups are having to link up with China's online giants.

"The cost of user acquisition is really high; start-ups cannot afford it any more," complains Ms Liu.

It could cost 300 yuan to acquire a new user, but that user may only ever spend 200 yuan, she says.

In the last year or so, "over half the unicorns" aligned with either Tencent or Alibaba, making "a bifurcation of the market into clans", says Mr Bean.

For start-ups wanting to train artificial intelligence models on big amounts of data, linking with Tencent, Alibaba, or Baidu creates huge advantages.

Unimaker founder Yang Yang says start-ups needs the access to tech giants' huge data stores

China has "a huge amount of data already", says Shenzhen resident Yang Yang, founder of Unimaker, a 3D printing start-up.

And big data helps Chinese start-ups localise and improve to beat overseas companies trying for a foothold.

This is how Meituan-Dianping, a Beijing group-buying site, beat off rivals Groupon, Didi Chuxing, Uber, and iQiyi, says Mr Yang.

Also, start-ups are selling more to businesses instead of consumers.

One or two years ago, "you'd see virtual reality start-ups targeting customers, like in the gaming industry", says Ms Liu.

"Now they're targeting businesses, like real estate and medical companies."

Could a period of belt-tightening be beneficial for China's start-up tech sector?

But there are advantages to China's tech bubble deflating.

For investors, things are "actually much better in a downturn than a hot period, so good companies have a chance to shine," says Mr Bean.

When everybody can get money, "it makes it difficult for the best to stand out", he says.

And increasing protests at the "996" working week give start-ups a chance to offer something different.

If you "don't want to be following 996 at big companies, maybe come work for my company," says Mr Prudhommeaux.

The slowdown may also force companies to focus more, believes Mr Norris. Chinese tech and internet firms are "rather infamous" for rambling across very different lines of business, he says.

Meituan, for example, is an online food platform that also acquired a bike share scheme.

But these non-core businesses drag down the companies' margins, argues Mr Norris.

"There's going to be a refocus on good, competent strategy - the art of choosing what not to do," he predicts.

So China's sunny gold rush days may be ending, but the coming winter may deliver a cold blast of efficiency that many tech firms need.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external