Does pornography still drive the internet?

- Published

Is Avenue Q's Trekkie Monster puppet right about porn and the internet?

Consider the opening lines of The Internet is for Porn, a song from the Broadway musical Avenue Q.

Kate Monster: "The internet is really, really great."

Trekkie Monster: "For porn!"

Kate Monster: "I got a fast connection so I didn't have to wait."

Trekkie Monster: "For porn!"

Innocent kindergarten teacher Kate Monster is trying to celebrate the usefulness of the internet for shopping and sending birthday greetings.

Meanwhile, her surly neighbour Trekkie Monster insists that people really value it more for more intimate activities.

Is he right? Sort of... but not really.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

Credible-seeming statistics suggest that about one in seven web searches is for pornography. This is not trivial - but of course it means that six in seven web searches are not.

The most-visited pornography website - Pornhub - is roughly as popular as the likes of Netflix and LinkedIn. That's pretty popular but still only enough to rank 28th in the world when I checked.

But Avenue Q was first performed in 2003, an age ago in internet terms, and Trekkie Monster might have been more correct back then.

New technologies often tend to be expensive and unreliable. They need to find a niche market of early adopters, whose custom helps the technology to develop.

Once it is cheaper and more reliable, it finds a bigger market, and a much broader range of uses.

There is a theory that pornography played this role in the development of the internet, and a whole range of other technologies. Does it stack up?

More things that made the modern economy

Since the very dawn of art, sex has always been a subject. Prehistoric cave-painters record buttocks, breasts, vulvas and comically large penises.

Carvings of copulating couples date back at least 11,000 years, to goat herders in Judea.

About 4,000 years ago, a Mesopotamian artist lovingly crafted a terracotta plaque of a man and woman having sex as she sips beer through a straw.

A couple of millennia later, the Moche in northern Peru depicted intercourse through the medium of ceramics. India's Kama Sutra dates from about the same time.

The Kama Sutra is perhaps the most celebrated work on love and sex

But just because people used the arts and crafts to depict erotica does not mean it was the driving force behind these techniques. There's no reason to think it was.

Consider Gutenberg's printing press. Although titillating books were certainly printed, the main market for reading material was religious.

A more plausible candidate, leaping ahead to the 19th Century, is photography.

Pioneering studios in Paris did a roaring trade in so-called "art studies", a euphemism the authorities didn't always accept.

Customers were willing to pay enough to fund the technology: for a time, it cost more to buy an erotic photograph than to hire a prostitute.

The word "pornography" derives from the Greek for "writing" and "prostitutes".

By the time of the next big technological breakthrough in artistic expression - the moving picture - the word had taken on its modern meaning.

But pornography didn't really drive the film industry, for obvious reasons.

Films were expensive. You needed a big audience to recoup your costs. That meant public viewings.

And while many people paid to look at pornographic pictures in the privacy of their home, far fewer people were comfortable watching an adult film in a public cinema.

Actor Debbie Rae poses in front of a series of "penny peepshow" machines showing short pornographic films

One solution came in the 1960s with the peepshow booth - an enclosed space where you'd put coins in a slot to keep a film playing.

One booth could bring in several thousand dollars a week.

But the real privacy breakthrough came thanks to the video cassette recorder (VCR).

In his book The Erotic Engine, writer Patchen Barss argues the VCR meant pornography "came into its own as an economic and technological powerhouse".

At first, VCRs were a hard sell: they were pricey, and they came in two incompatible formats - VHS and Betamax.

Who would risk plunging a significant chunk of cash into a device that might soon be obsolete? People who really wanted to watch adult films at home, that's who.

Linda Lovelace starred in the very successful X-rated video release Deep Throat, although later complained she had been forced to take part, and became an anti-porn campaigner

In the late 1970s, most videotape sales were pornographic.

Within a few years, the technology was more affordable for people who wanted to watch family films - and as the market expanded, pornography's share of it shrank, external.

A similar story can be told about cable television - and, yes, the internet.

Older readers might remember when getting online meant coaxing a dial-up modem into establishing a connection, then fretting about phone charges as it slowly chugged through a file that would nowadays download in the snap of a finger.

What would motivate an ordinary person to persevere? You've guessed it.

A few years later, research into internet chat rooms indicated a similar proportion of activity devoted to sex.

So in those days, Trekkie Monster's analysis wouldn't have been far wrong.

And, as he suggests to Kate, appetite for pornography helped to drive demand for faster connections: better modems and higher bandwidth.

It spurred innovation in other areas, too. Online pornography providers were pioneers in web technologies, such as video file compression and user-friendly payment systems, and in business models, such as affiliate marketing programmes.

All these ideas went on to find much wider uses. And as the internet expanded, it gradually became less for pornography and more for all that other stuff.

Nowadays, the internet is making life hard for professional pornographers.

Just as it's hard to sell a newspaper subscription or a music video when so much is available free online, it's hard to sell pornography when sites such as Pornhub are giving it away.

Much of this free pornography is pirated and it's an uphill struggle to get the illegally uploaded content removed, external, as Jon Ronson chronicles in his podcast series The Butterfly Effect, external.

Casey Calvert has shot hundreds of "custom" pornography films in recent years

One emerging niche is to produce "custom" pornography, for clients such as the man who paid adult star Casey Calvert - and others - to contemptuously destroy his stamp collection on film, external.

But, of course, what's bad for the content creators is good for the aggregator platforms, which make their money through advertising and premium subscriptions.

The big player in pornography at the moment is a company called Mindgeek, which owns Pornhub and several other top adult websites, external.

Its absolute dominance of the market is a problem, according to Prof Marina Adshade, of the Vancouver School of Economics, author of Dollars and Sex: How economics influences sex and love.

"Having a single buyer has put pressure on producers to lower the price of their films," she says.

"This hasn't just cut into pornographers' profits, it has radically changed the work of porn actors, who are now under greater pressure to perform acts that they would have been able to refuse in the past - and at a lower price."

In Avenue Q, Trekkie Monster appears to do nothing all day but surf for pornography, so the other characters are surprised when he reveals he's a multi-millionaire.

His explanation? "In volatile market, only stable investment is… porn!"

And, once again, Trekkie Monster is nearly right, but not quite.

For sure, there's money in pornography.

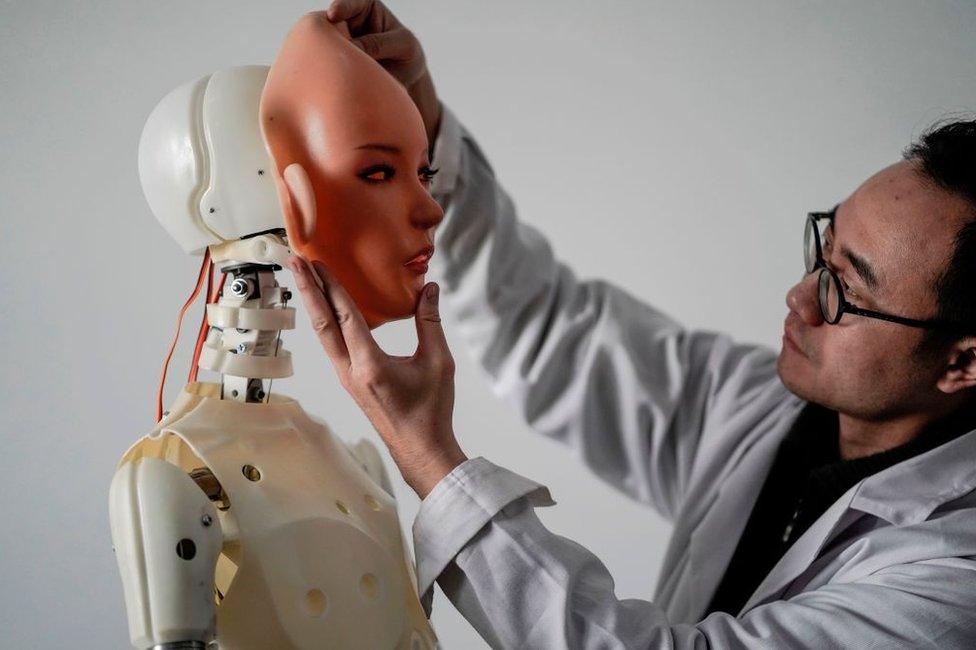

Will sex robots become an increasing presence in pornography?

But the best way to make it may be to invest in the technologies that enable it and which it enables.

In the past, that meant Parisian photo studios or companies making VCRs or high-speed modems; today, Mindgeek's algorithms that suggest content and keep eyeballs on screens.

And what will Trekkie Monster be singing in the future? "Robots are for porn", perhaps?

The role of sex in accelerating technology is unlikely to be finished yet.

The author writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published17 April 2019

- Published4 December 2018

- Published29 November 2018

- Published10 August 2017

- Published22 December 2016

- Published9 May 2014

- Published15 August 2013