Killed for spying: The story of the first factory

- Published

Piedmont was renowned for its innovative mechanised silk production

Piedmont, in north-west Italy, is celebrated for its fine wine. But when a young Englishman, John Lombe, travelled there in the early 18th Century, he was not going to savour a glass of Barolo. His purpose was industrial espionage.

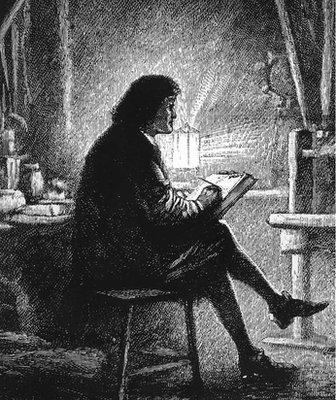

Lombe wished to figure out how the Piedmontese spun strong yarn from silkworm silk. Divulging such secrets was illegal, so Lombe sneaked into a workshop after dark, sketching the spinning machines by candlelight. In 1717, he took those sketches to Derby in the heart of England.

Local legend has it that the Italians took a terrible revenge on Lombe, sending a woman to assassinate him.

Whatever the truth of that, he died suddenly at the age of 29, just a few years after his Piedmont adventure.

While Lombe may have copied Italian secrets, the way he and his older half-brother used them was completely original.

The Lombes were textile dealers, and seeing a shortage of the strong silk yarn called organzine, they decided to go big.

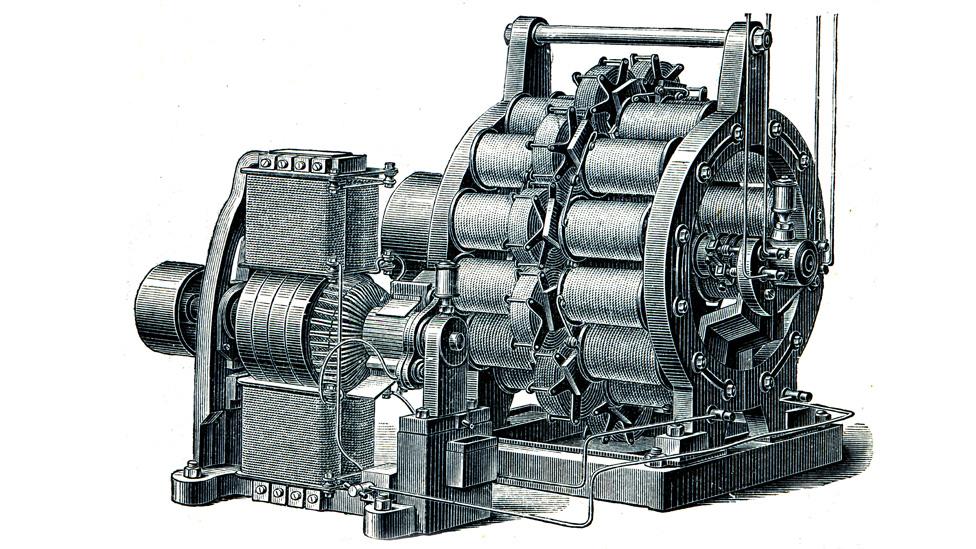

In the centre of Derby, beside the fast-flowing River Derwent, the Lombe brothers built a structure that was to be imitated around the world: a long, slim, five-storey building with plain brick walls cut by a grid of windows.

The building, completed in 1721, housed three dozen large machines powered by a 7m-high waterwheel. It was a dramatic change in scale from what had been done before. The age of the large factory had begun with a thunderclap.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

It is a testament to the no-nonsense functionality of the Derby silk mill that it operated for 169 years, pausing only on Sundays, and for droughts - when the Derwent flowed slow and low.

Over that period of time, the world economy grew more than fivefold, and factories were a major part of that growth.

Intellectuals took note. Author Daniel Defoe came to gaze in wonder at the silk mill. Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776, begins with a description of a pin factory. Three decades later, William Blake penned his famous line about England's "dark Satanic Mills".

Concerns about the conditions in factories have persisted ever since. Critics claimed that factory exploitation was a similar evil to slavery, a shocking claim then and now.

After visiting the mills of Manchester in 1832, the novelist Frances Trollope wrote that factory conditions were "incomparably more severe" than those suffered by plantation slaves.

The recruiting wagons which toured the rural areas of 1850s Massachusetts hoping to persuade "rosy-cheeked maidens" to come to the city to work in the mills were dubbed "slavers".

Friedrich Engels, whose father owned a Manchester factory, wrote powerfully about the harsh conditions, inspiring his friend Karl Marx.

But Marx, in turn, saw hope in the fact that so many workers were concentrated together in one place: they could organise unions, political parties, and even revolutions. He was right about the unions and the political parties, but not about the revolutions: those came not in industrialised societies but agrarian ones.

The Russian revolutionaries were not slow to embrace the factory.

In 1913, Lenin had condemned the stopwatch-driven, micromanaging studies of engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor as "advances in the extortion of sweat". After the revolution, the stopwatch was in the other hand, with Lenin announcing: "We must organise in Russia the study and teaching of the Taylor system."

In developed economies, Blake's dark Satanic Mills gradually gave way to cleaner, more advanced factories, although of course as Financial Times reporter Sarah O'Connor says, exploitative factories do still exist. However, it is the working conditions of factories in developing countries that now attract the most attention.

Economists have tended to believe that sweatshop conditions beat the alternative of even more extreme poverty in rural areas, and they have certainly been enough to draw workers to fast-growing cities around the world. Manufacturing has long been viewed as the engine of rapid economic development.

More Things That Made the Modern Economy:

So what lies next for the factory? History offers several lessons.

Factories are getting bigger. The 18th Century Derby silk mill employed 300 workers, a radical step at a time when even machine-based labour could take place at home or in a small workshop. The 19th Century Manchester factories that had horrified Engels could employ more than 1,000 people, often including women and children.

Modern factories in advanced economies are much larger still: Volkswagen's main factory in Wolfsburg, Germany employs more than 60,000 workers - half the town's population.

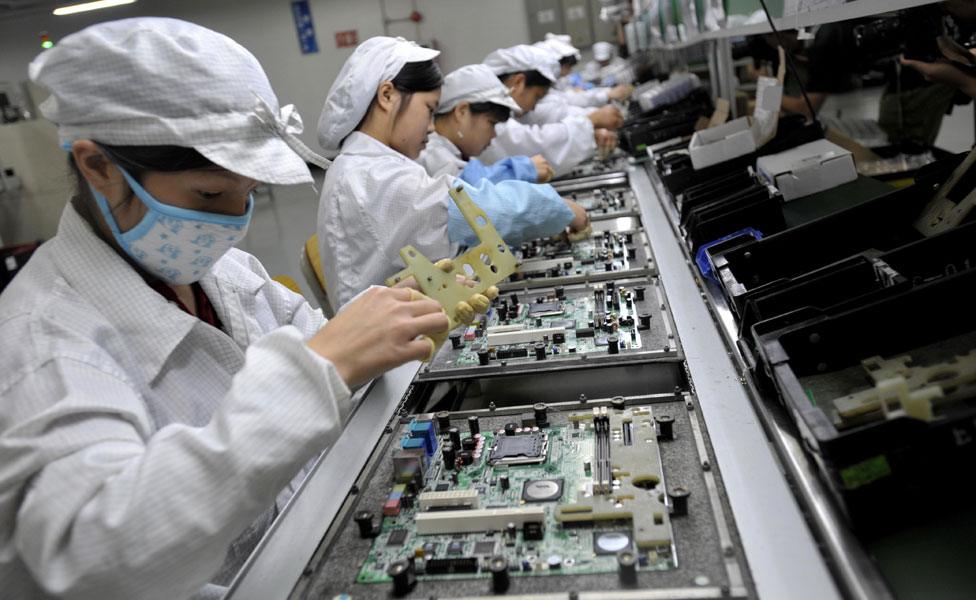

And the Longhua Science and Technology Park in Shenzhen, China - better known as Foxconn City - employs at least 230,000 workers (and by some estimates 450,000) to make Apple's iPhones and many other products.

These are staggering numbers for a single site: the entire McDonald's franchise worldwide has fewer than two million employees.

The increase in scale is not the only way in which Foxconn City continues the arc of history.

There are - as there were in the 1830s - fears for the welfare of workers. In Shenzhen, after a series of worker suicides, the company installed nets which are designed to catch anyone who leaps from the roof, while it also increased wages and reduced working hours.

A protective net added to a Foxconn employee dormitory in Shenzhen

Large strikes are commonplace in China, but as the FT's Yuan Yang notes, in one of history's great ironies, the Chinese government cracks down hard on the young Marxists who try to get the workers unionised.

And, as in the West many decades before, there has been some progress. Veteran journalist James Fallows, who has visited 200 Chinese factories,, external says that conditions have dramatically improved over time.

Trade secrets kick-started the first factory, and have shaped factories ever since.

Richard Arkwright, whose 1770s cotton mill was modelled on the Lombe brothers' silk mill, vowed: "I am Determin'd for the [future] to Let no persons in to Look at the [works]."

Chinese factories are still secretive: Mr Fallows was surprised to be allowed into the Foxconn plant, but he was told that he must neither show nor mention the brand names coming off the production lines.

One thing, however, has changed.

Factories used to centralise the production process; raw materials came in, finished products went out. Components would be made on site or by suppliers close at hand. This saved on the trouble of transporting heavy or fragile objects in the middle of the manufacturing process.

But today's production processes are themselves global.

Production can be co-ordinated and monitored without the need for physical proximity, while shipping containers and barcodes streamline the logistics.

Modern factories - even behemoths like Foxconn City - are only steps in a distributed production chain. Components move backwards and forwards across borders in different states of assembly.

Workers in Foxconn City, for example, do not make iPhones.

As it says on the back of every handset, they are designed by Apple in California, but "assembled" in China, using glass and electronics imported from Japan, Korea, Taiwan and even the USA itself.

Huge factories have long supplied the world. Now the world itself has become the factory.

The author writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published4 May 2018

- Published21 August 2017

- Published5 June 2017

- Published6 February 2017

- Published9 January 2017