The tropical islands that fell into ruin

- Published

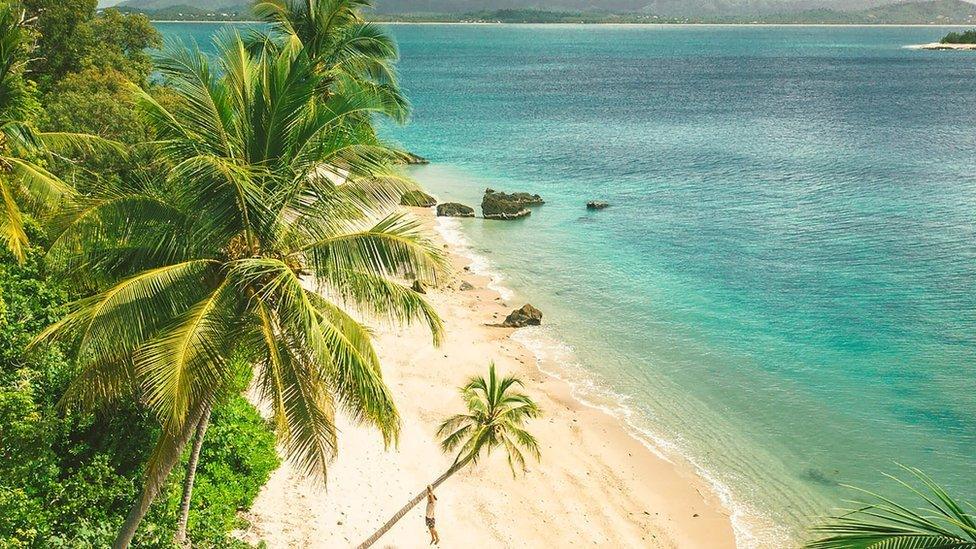

Dunk Island is on the market for around A$20m (£11m)

In recent years, Dunk Island off Australia's Queensland coast has been the private holiday retreat of its owners.

Prior to 2011, the picturesque island that lies near the country's Great Barrier Reef, had a 160-room resort. But it was destroyed that year by a cyclone.

At the time tourism across the wider region was struggling. So instead of refurbishing the hotel, the owners pocketed the insurance payout and decided to enjoy Dunk for themselves.

Now it's on the market with an asking price of around $20m Australian dollars ($14m; £11m).

Tom Gibson, who is managing the sale at estate agency group JLL, says the lucky bidder will get the "old bones" of the resort, a Qantas-built airstrip, mains power, and a sewage treatment plant.

He says the current owners want to sell to someone who can "bring the operation back to life".

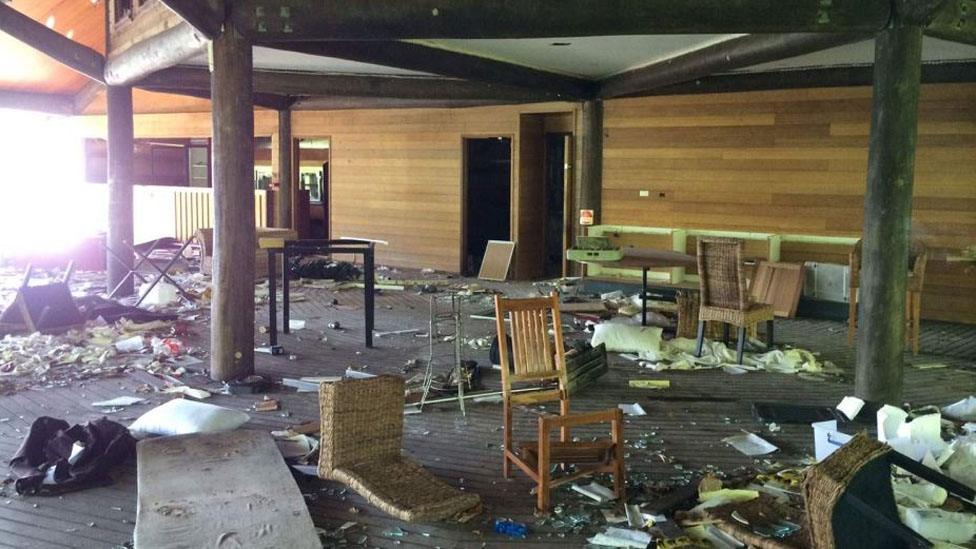

The hotel on Dunk Island was badly damaged by a cyclone in 2011

Dunk's fortunes form part of a picture of decline that mars resorts along Australia's iconic reef.

It is one of a string of retreats that have fallen into ruin as powerful cyclones and rising competition have damaged tourism. Investment has suffered, and a handful of island hotels lie derelict.

"We can't rely on past glories as the quintessential holiday destination for Australians," says Daniel Gschwind, chief executive of the Queensland Tourism Industry Council.

"This is actually a race and we have to stay fit," he says, adding it has "taken us a little while to realise that and respond".

Roughly the size of Italy, the Great Barrier Reef stretches 2,300km (1,400 miles) along the Queensland coastline.

Central to island tourism on the world's largest coral reef is the cluster of resorts in the Whitsundays.

Right now, Mr Gschwind says that four of the seven Whitsunday Islands that have tourist accommodation are closed.

Dunk Island is located off the far north Queensland coast

That's partly due to severe cyclones that have battered the region, notably Cyclone Debbie in 2017.

Yet the devastation it caused went far beyond damage to property, Mr Gschwind explains, as coverage of natural disasters can knock tourism long after the sunshine has returned.

"Those perception impacts for our industry are often more catastrophic than the physical damage caused," he says.

Mr Gschwind adds that some businesses suffer no damage, but stand "on the brink of collapse" as tourists stay away for fear it's unpleasant or unsafe.

"It's depressing when you go to these places and it's bright sunshine, it's warm [and] people are sitting around with no customers for no apparent reason."

Wild weather isn't the only factor that has dampened island tourism. A strong Australian dollar, coupled with a surge in budget air fares, dealt a heavy blow to many tourism operators.

Observers say that intensified about a decade ago, when instead of holidaying at home, Australians could afford more exotic trips to places like Bali or Phuket. For international travellers, Australia looked too pricey.

"The strength of the currency is the biggest driver in the Australian tourism market," says Sam Charlton, co-owner of Bedarra Island, a 10-villa luxury resort off the north Queensland coast.

The World Heritage-listed Great Barrier Reef is under threat from coral bleaching

Mr Charlton and his wife Kerri-Ann took over Bedarra in 2011. At that time, the global financial crisis was weighing on tourism, and the high dollar made matters worse.

He says when Cyclone Yasi hit in 2011 it created "the perfect storm of negatives" for island operators.

It was the start of a period of deterioration for many resorts in the region. With tourist arrivals thinning and money drying up, upkeep began to slip.

"The result now is a collection of islands that have buildings on them that haven't been looked after for 10 years," Mr Charlton says.

Some islands closed when times were tougher, he says, and now "there's a lot of work to do" to revive the industry.

But much of that work has begun. Investment is flowing back into the region through a wave of redevelopment.

Cape Richards resort on Hinchinbrook Island is another abandoned former holiday destination

Daydream Island resort officially reopened this month, and Great Keppel - a former party island with the marketing slogan "Get wrecked on Keppel!" - was bought by a Singaporean-Taiwanese company in 2018.

An Intercontinental resort on Hayman Island is due to open next month, and Lindeman Island is slated for a A$583m revamp. Another, Long Island, is reportedly on the market for around A$15m.

Mr Gibson's firm JLL has managed a number of Queensland island sales over the past few years. He says the region "let the guard down a bit from 2005 onwards with the lack of reinvestment", but that's changing.

This month, the Queensland government said it would invest more than A$55m, external to partner with the private sector "to restore these resorts to their former glory".

Global Trade

Already, tourism is picking up. Industry group Tourism and Events Queensland says 7.7 million people visited the regions connected to the Great Barrier Reef in 2018 - up 13% year-on-year.

That's providing a boost to a valuable sector. A 2017 Deloitte report found the Great Barrier Reef supports 64,000 jobs and contributed A$6.4bn annually, external to the Australian economy.

Still, some are worried about the impact of change. Conservation groups have raised concerns over plans to develop islands such as Hinchinbrook, one of Australia's largest island national parks, by leasing them to commercial interests.

The Greet Barrier Reef stretches for 2,300km

The health of the reef itself is also in sharp focus. The threat of climate change and rising sea temperatures following widespread coral bleaching has sparked concerns about its future.

Those fears aren't helping the tourism industry, Bedarra Island's Mr Charlton says.

"It's frustrating as a [resort owner] that there is all this press that the reef is dying… it's not".

He argues the reef is "actually in really good condition".

"The poor old reef has copped a lot of negative publicity that it doesn't deserve. To the point where we get guests coming to see the reef before it's all gone. And then they get back from their reef trip and they say it's spectacular, it's full of life and colour - and it is."

- Published16 April 2018

- Published27 April 2018

- Published29 April 2018