Tesla motors make classic Ferraris go faster

- Published

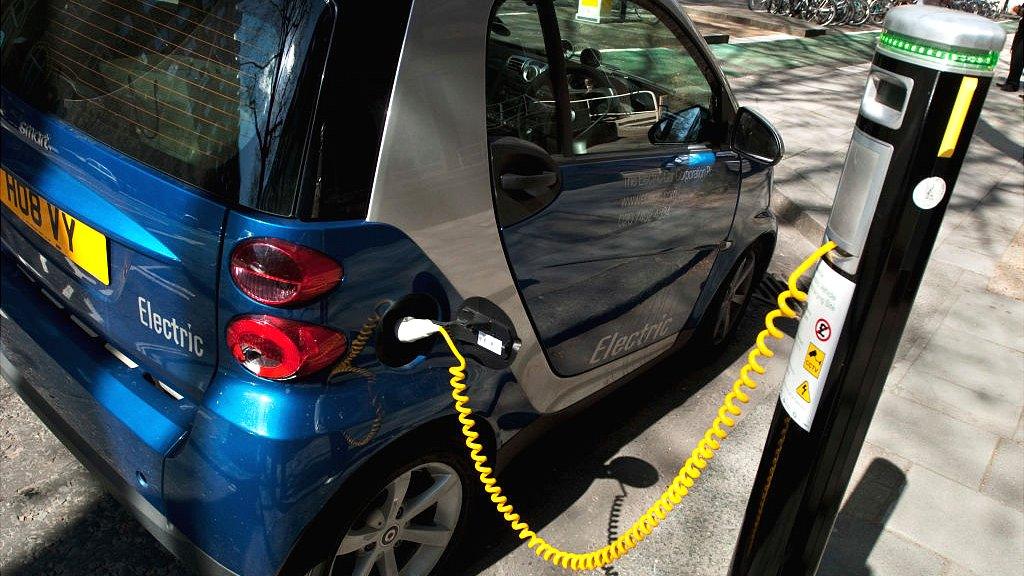

Matthew Quitter converted a Morris Minor to electric to zip around central London

Every time a Tesla hits a tree, it's a gift for these enthusiasts.

Around the world, a cottage industry is growing in converting classic cars into electric vehicles.

Small firms are buying up old Nissan and Tesla parts and bolting them into Ferraris, Porsches and BMWs, making them cleaner, easier to maintain and even quicker.

The basic process differs little from firm to firm: take out the engine and fuel tank and replace them with a battery pack and motor, often connecting the motor to the old gear box.

They try to change as little as possible so that the process is reversible.

Richard Morgan says he's been an electric convert for at least the last three years

Buyers have never asked for their car to be put back to petrol, says Richard Morgan, who owns Electric Classic Cars, external in Newtown, Wales. In fact, nobody has asked them to keep their petrol engine in storage, either - a service he offers.

"I'm talking as an ex-petrolhead," he says. "From a massive petrolhead's point of view, electric cars are better in every way." However he adds: "If you'd said that to me five years ago I'd have laughed".

'Faster, better'

Mr Morgan, whose more exotic conversions include a Ferrari 308, says his interest started a few years ago in his days racing classic cars. His team used an Oset electric bike to ferry about parts and snacks.

"I was always amazed by that little thing. How much power was in this little motor the size of your fist."

So he decided to apply that power to cars, making it a full-time job three years ago. He uses a mix of new and recovered parts.

Mr Morgan's conversions include this 1974 BMW E9 and a Porsche 911 Targa

"It was nothing environmental, purely from a car point of view. How can I make it faster, better, more reliable?"

The Ferrari will now go from 0-60mph in 3.5 seconds in good conditions, halving its petrol-driven time. Its owner can worry less about tune-ups and break-downs, he says.

The car could do it in 2.7 seconds, but this was toned down as the rest of the car wasn't strong enough to handle it.

'We save cars'

This car-first view is shared by San Diego-based EV West, external founder Michael Bream, considered one of the early movers of today's conversion scene.

He says while many people will want to go electric for the cleaner air, "our job is to save the car".

Mr Morgan also sells chargers and is starting to convert motorbikes

This approach is proving good for a range of firms, and Tesla and its competitors are proving good benefactors beyond their bounty of scrap yard parts.

Battery cars have been around for a long time, but Tesla made them fun, says Mr Bream. And fun is a lot more persuasive than bossy.

"'Your car pollutes, your car's stinky'. I don't know if people have ever parented before, but saying something like that is the worst thing you can do."

Government help

Fun can also trump basic economics, he adds. "I've never in my life had somebody in a Prius pull up to me and say, 'dude, come and try this thing, it is ridiculously economical'."

His advice to would-be customers is to choose a car that will stay attractive to buyers. While new cars lose value the moment they leave the showroom, classics like old Porsches and the VW Beetle are more likely to keep their value, or even appreciate.

Brandon Hollinger converted a black cab and would like to make the process cheaper and easier

For Matthew Quitter of London Electric Cars, external, the process could be extended to cars beyond classics.

He admits that government help might be needed to compete with cheaper, newer mass-market electric cars and the thin margins big manufacturers work on.

Expensive to do

Scrap parts would need to stay cheaper than second-hand cars, he says, and conversion costs would need to fall.

Currently it is not cheap and can cost £20,000 or more. Many conversions are the first of their kind, adding to the expense.

Motors are much easier to maintain than engines, says Matthew Quitter

But the more it is done, the cheaper it gets. As well as avoiding scrapping millions of working petrol car bodies, it will mean a generation of mechanics will still recognise at least most of the car's layout.

"Otherwise, you will get a moment where everyone is driving electric cars and no-one will know how to fix them," says Mr Quitter.

His tip: less-fashionable classics like the Triumph Herald, a "fabulous little car. You can pick them up for a couple of grand."

'Ultimate recycling'

City dwellers like him don't need the range of a Tesla for their commute, and using batteries from old laptops destined to be scrapped or recycled could prove a cheap way of converting the family car.

Brandon Hollinger, whose Lancaster, Pennsylvania firm ampRevolt, external has converted cars including a London black cab, thinks all-in-one kits could cut costs. For him it would be "the ultimate in recycling".

Richard Morgan says he can "enjoy classic cars again" without worrying about overheating and breakdowns

"Imagine an assembly the size of an engine that contains not only the motor, but also the battery and electronics - and boom, labour costs are way down," he says.

"I do see this as a promising direction. I could do the expensive builds for ever and it's fun but I would rather crack the code and make this available to more people."

'Racing to the people'

But Mr Morgan and Mr Bream both caution that the market for cheaper electric cars will only increase, reducing prices and making it a very competitive field.

Katherine Legge says electric racing cars help showcase new technology

Katherine Legge, one of Britain's top racers, demurs when asked which is her favourite out of petrol and electric. "It's just totally different. I don't think you can compare the two. There's room for both."

But racing electric cars does have its advantages, she says. "You can take racing to the people. You can have a conversation while you are watching your favourite driver go by. We can race on downtown city streets because there are no emissions, noise pollution."

Just a long tailpipe?

The industry has many converts. Why wouldn't you want to make your car faster, easier to look after and cleaner, if you have the money?

Formula E racing is possible in places like New York, where noisier Formula 1 would not be so welcome

Critics grumble about vandalising pieces of history and the loss of the engine noise. A few point out that globally, most electricity is still generated from coal and oil. The engineers give these points short shrift.

"In your Edwardian house, do you still have a coal fire? Have you ruined it by putting in central heating?" asks Richard Morgan.

For him, the noise is lost power that should be used to make your car go faster, and its absence means hearing the countryside again. As for the long tailpipe argument?

"If petrol was invented now, it would not take off," he says. It needs to be discovered, refined and shipped about the country. And the portion of renewables used by the grid is ever increasing, he adds.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external

- Published9 July 2019

- Published18 July 2019

- Published6 March 2019