What can Silicon Valley learn from tinned food?

- Published

If you played a word-association game with the phrase "Silicon Valley", you would be unlikely to come up with the phrase "tinned food".

Silicon Valley stands for cutting-edge technology, bold ideas that change the world. Nobody would say the tin can was cutting-edge technology, although the more literal-minded might make that claim for the tin-opener.

Yet, in its day, tinned food was as revolutionary as anything now being pitched by Bay Area start-ups.

And its story reveals how surprisingly little some deep dilemmas around innovation have changed in the past 200 years or so.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

First, how do we incentivise good ideas?

There's the lure of a patent, of course, or first-mover advantage. But if you really want to encourage fresh thinking, offer a prize. Self-driving cars are a good example.

In 2004, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa) offered $1m (£600,000 at the time) to the first vehicle to find its way across a course in the Mojave Desert, external.

The result was pure Wacky Races - vehicles caught fire, flipped over, crashed through fences and ground to a halt because they were confused by tumbleweed, external. The prize was unclaimed.

However, a year later, the Stanford Team successfully completed the second round of the Grand Challenge, winning $2m (£1.6m) for its efforts, and within a decade, autonomous cars were reliable enough to let loose on public roads.

The Darpa prize was hardly the first competition to encourage innovation.

In 1795, the government of France offered a prize of 12,000 francs for inventing a method of preserving food. It was eventually claimed by Nicolas Appert, a Parisian grocer and confectioner credited with the development of the bouillon or stock cube and - less plausibly - the recipe for chicken Kiev.

Through trial and error, Appert found if you put cooked food in a glass jar, plunged the jar into boiling water and then sealed it with wax, the food wouldn't go off.

Why was the French government interested in preserving food? For the same reason Darpa was interested in vehicles that could navigate themselves across deserts - with a view to winning wars.

Napoleon Bonaparte was an ambitious general when the prize was announced. By the time it was awarded, he was France's emperor, about to launch his disastrous invasion of Russia. Napoleon may or may not have said: "An army marches on its stomach," but he was clearly keen to broaden his soldiers' provisions from smoked and salted meat.

Appert's laboratory was an early example of a common phenomenon - military needs spurring innovations that transform the economy.

From GPS to Apple's iPhone to Arpanet, which became the internet, Silicon Valley is built on technologies first funded by the US Department of Defense.

Many of the technologies that made the iPhone possible in 2007 came from the US military

But even when ideas come from the public sector, it sometimes takes a culture of entrepreneurship to explore what they can do.

Appert wrote up his culinary experiments in a book later published in English as The Art of Preserving All Kinds of Animal and Vegetable Substances for Several Years.

Meanwhile another Frenchman, Philippe de Girard, started applying the techniques to containers made of tin, not glass. But when he wanted to commercialise his idea, he decided to sail across the English Channel.

Why? Too much French bureaucracy, according to Norman Cowell, former lecturer in food science at Reading University.

He argues Britain's financial system of the time was entrepreneurial, with plenty of venture capitalists prepared to take risks.

More things that made the modern economy:

Girard employed an English merchant to patent the idea on his behalf - a necessary subterfuge, as Britain was at war with Napoleon - and an engineer and serial entrepreneur, Bryan Donkin, bought the patent for the tidy sum of £1,000.

A modern-day Girard, looking for a place with venture capital and risk-taking attitudes today, would surely head for Silicon Valley.

For decades, others have tried to emulate its knack for generating ideas and growing businesses - to create an "innovation ecosystem", in the current parlance, external. But none has yet quite measured up.

Economists can confidently tell you some ingredients for an innovation ecosystem, such as making businesses easy to set up and encouraging links with academic research. But nobody has yet perfected the recipe.

One ingredient that's much debated is how best to regulate. Lack of red tape may have helped attract Girard to England but tinned food was about to demonstrate why rules and inspections do serve a purpose.

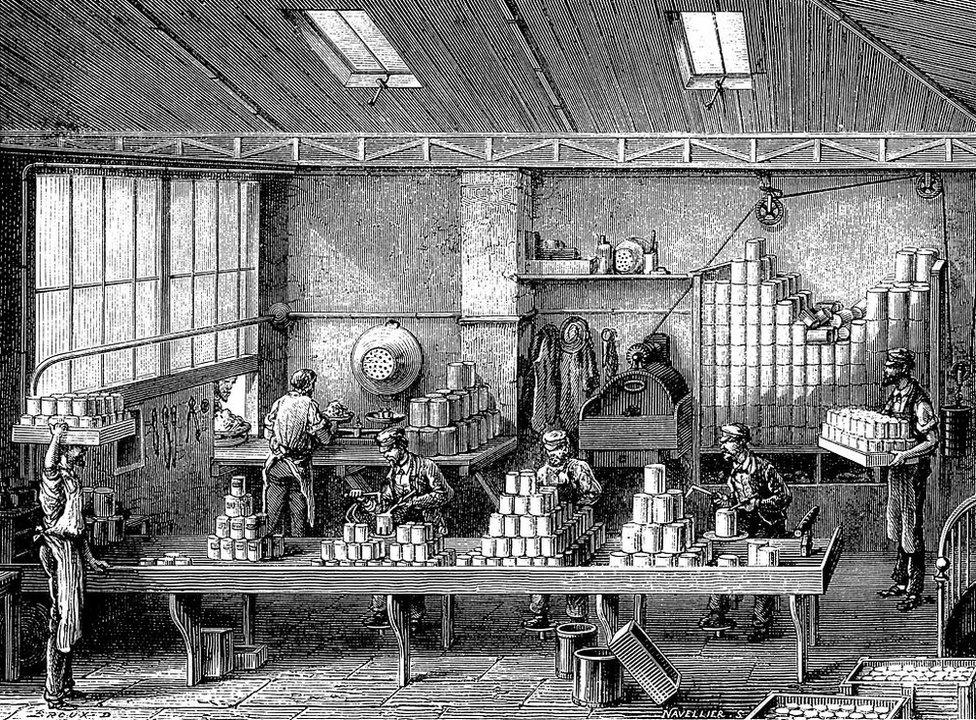

By 1845, with Donkin's patent now expired, Britain's navy decided to save money by finding a cheaper supplier. This proved unwise.

After complaints from sailors, naval inspectors started checking the wares. On one occasion, they tested 306 tins and found only 42 to be edible. The rest contained such delicacies as putrid kidneys, diseased organs and dog tongues.

As Sue Shephard notes in her history of food preservation, Pickled, Potted and Canned, the scandal hit the newspapers at an unfortunate time.

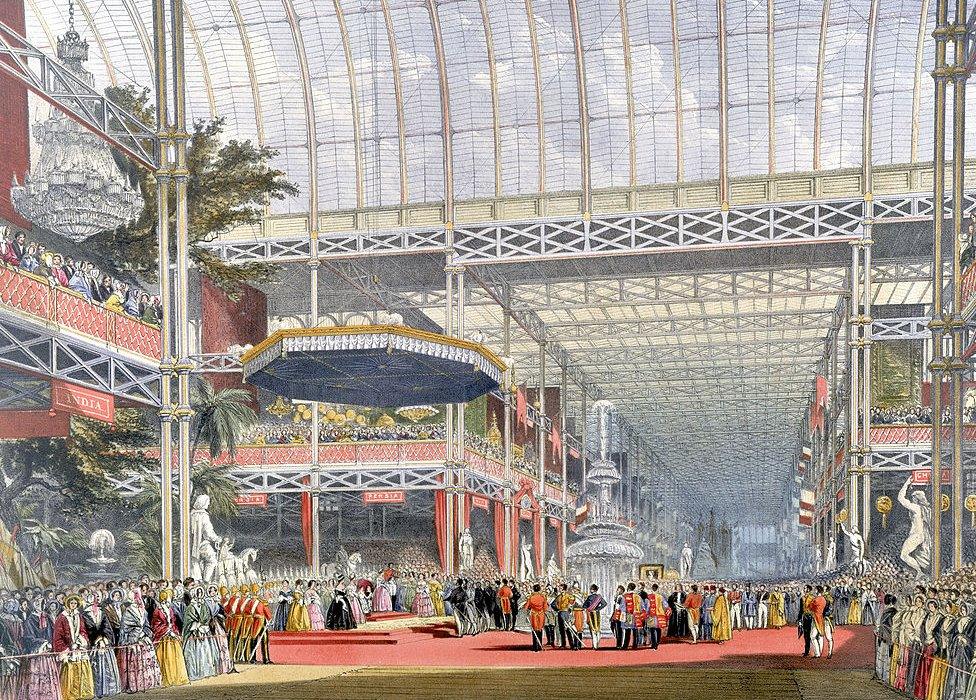

The Great Exhibition of 1851 had just introduced ordinary Londoners to tinned delights hitherto stocked by luxury food stores only.

There were sardines and truffles, artichokes and turtle soup. Putrid kidneys were not supposed to be part of the narrative. With quality improving and prices coming down, tinned food had seemed set for the mass market - but it took years to rebuild public confidence.

That mass market seemed self-evidently desirable. With refrigeration yet to be invented, safe tinned food would widen people's diets and improve nutrition.

But it's not always so easy to anticipate how new technologies will play out and whether regulators should try to speed them up or hold them back, nudge them in a certain direction or leave well alone.

Will artificial intelligence hugely widen inequality? Should governments step in? How?

These are debatable questions but some Silicon Valley types are sufficiently concerned about where their innovations may be taking us they're seriously imagining apocalyptic scenarios.

We're "skating on really thin cultural ice right now", one former Facebook manager told the New Yorker magazine, external, explaining why he's bought land on an island and stocked up on ammunition. Others have bought underground bunkers and have planes on constant standby in case society implodes.

These "preppers", by one estimate, include at least half the billionaires in Silicon Valley.

Progress can certainly be fragile, as Nicolas Appert found to his cost.

He invested his 12,000 francs prize money in expanding his canning operation, only to see it destroyed by invading Prussian and Austrian armies as Napoleon's rule collapsed.

The world looks more stable now and the Silicon Valley preppers are probably worrying too much - but if their worst fears are realised, one of the world's most valuable commodities might yet be… tinned food.

The author writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published30 January 2019

- Published27 July 2018

- Published21 April 2013

- Published12 March 2019

- Published10 April 2019

- Published20 November 2017