Behind the wheel of a hydrogen-powered car

- Published

Asian car makers lead the hydrogen car market

It's a question I couldn't avoid as I drove across central England in a borrowed car powered by a hydrogen fuel cell.

The Hyundai ix35 was fast, eerily quiet - they've installed a little electronic jingle so you can tell when you've switched it on - and there was a reassuring 230 miles (370 km) left on the clock.

And best of all, I drove with the smug knowledge that when a vehicle is powered by hydrogen, the only exhaust product is water.

Quite a difference from my own 13-year-old, one-litre petrol engine: noisy, slow and undeniably dirty.

So why, I wondered, is this clean, green technology lagging far behind the hybrid and all-electric sectors?

The relatively small hydrogen market is dominated by the Asian giants: Toyota, Honda and Hyundai.

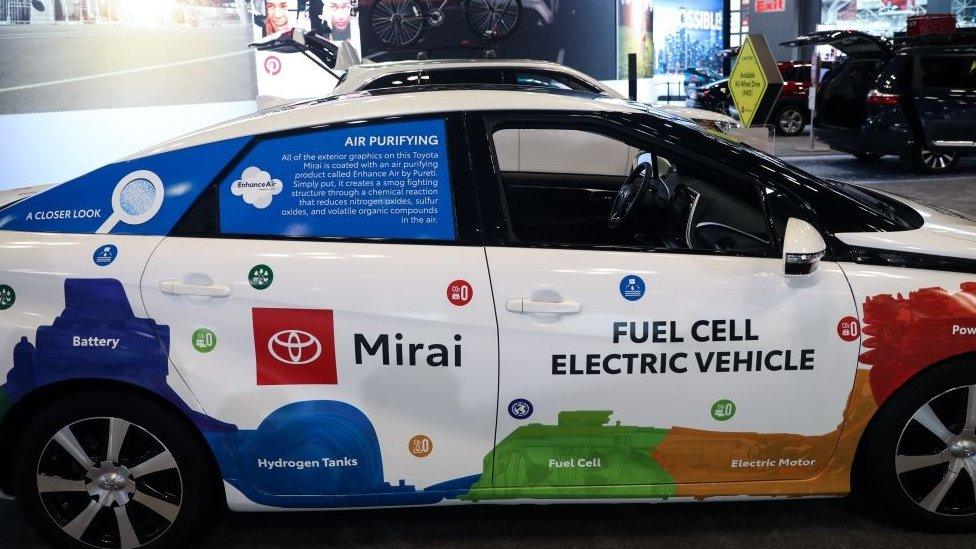

Toyota's hydrogen-powered car - the Mirai

In early October in Tokyo amid great razzmatazz, Toyota unveiled its latest fuel cell Mirai saloon, which it hopes to launch in late 2020.

European brands including BMW and Audi are also fine-tuning their own hydrogen vehicles.

But this is a sector in which the upstart start-up can claim a modest place too.

Outside Llandrindod Wells, a small market town in central Wales, Riversimple aims to lease, not sell, its futuristic hydrogen fuel cell vehicles to a strictly local market.

They have just two cars on the road so far, with Numbers 3 and 4 under construction in Riversimple's meticulously clean production facility.

"The car's called the Rasa - as in tabula rasa, or clean slate," says the company's founder and chief executive, Hugo Spowers.

Riversimple's fuel cell was originally designed for fork-lift trucks

"We're using fuel cells off the shelf: ours was made for fork-lifts for Walmart warehouses."

The Rasa will do a tidy 60mph (100km/h) and has a range of around 300 miles (480km) on a single 1.5 kg hydrogen tank.

"In purely calorific terms," Spowers concludes, "our car is doing the equivalent of 250 miles to the gallon."

That sounds impressive - so how do hydrogen powered cars work?

At the heart of the car is a fuel cell, where hydrogen and oxygen are combined to generate an electric current, and the only by-product is water. There are no moving parts in the fuel cell, so they are more efficient and reliable than a conventional combustion engine.

While the cars themselves do not generate any gases that contribute to global warming, the process of making hydrogen requires energy - often from fossil fuel sources. So hydrogen's green credentials are under question.

Using hydrogen and fuel cells is a very clean tech

And then there is the question of safety. Hydrogen is a notoriously explosive gas.

That's why manufacturers disclose plenty of reassuring detail on their websites.

The Toyota Mirai, for example, boasts triple-layer hydrogen tanks capable, the company says, of absorbing five times as much crash energy as a steel petrol tank.

The twin hydrogen tanks in the Honda Clarity are similarly robust featuring layers of aluminium and carbon fibre and designed to resist both extreme pressure and extreme heat.

Still, not everyone is convinced.

EuroTunnel does not allow "vehicles powered by any flammable gasses", including hydrogen, to use the link between the UK and France.

Riversimple cars have a range of about 300 miles

The Riversimple business model - a three-year fixed price lease aimed at short-distance local drivers - is designed to negate the biggest problem affecting hydrogen cars: range anxiety.

With just 17 pumps across Britain, refuelling is a challenge, so the industry is stuck.

The public won't commit if they can't guarantee a refill wherever they need to drive, but hydrogen production companies are reluctant to install expensive pumps unless there's likely to be a consistent take-up.

According to Jorgo Chatzimarkakis, secretary-general of the pro-hydrogen group H2Europe, a country like Germany has around 75 hydrogen fuelling stations - but there aren't enough drivers.

He blames car markers for being slow to produce hydrogen-powered cars. He points out that BMW isn't launching one until 2022 and Audi in 2025. "This is definitely quite late," he says.

Mr Chatzimarkakis wants to prioritise a pan-European network of 20 to 30 pumps aligned along a "north-south corridor" to enable hydrogen-powered vehicles - especially larger freight-bearing lorries - to travel freely where business needs dictate.

The Hydrogen4ClimateAction conference in Brussels in mid-October led to investment pledges by European governments of more than €50bn (£43bn; $56bn) in hydrogen research and infrastructure.

"We at H2Europe are match-makers because this is a co-operative job - it cannot be done by industry alone; it cannot be done by politics alone," Mr Chatzimarkakis says.

A lack of fuel stations is holding back hydrogen vehicles

That collaboration is evident in California, which is experiencing the flip-side of the car/pump imbalance: there are queues at filling stations.

If you visit the website of the Alternative Fuels Data Center, part of the US Department of Energy, and click on "fuelling station locations", you'll get 42 results - all in California.

"We are laser-focused on building out an infrastructure to refill zero-emission vehicles," says Patricia Monahan, science and engineering specialist on the California Energy Commission (CEC).

As importantly, California is committed to incentives for both producers and consumers in the fuel cell sector, she says.

Anyone buying a new hydrogen car will get an incentive of $2,500, with similar subsidies from both the CEC and the state's Air Resources Board aimed at persuading heavy-duty vehicle companies to look into zero-emission alternatives.

"We are really testing out for the world," Ms Monahan says, "how to develop an infrastructure to refuel these vehicles, and policies to incentivise their production."

Chinese firms have been investing heavily in hydrogen-powered cars

In fact, even California may be behind the curve.

According to Andy Walker, technical marketing director at Johnson Matthey Fuel Cell in the UK - itself a sector pioneer since 2003 - several Asian nations are making dramatic commitments to hydrogen.

"The Chinese government has a target of more than a million fuel cell vehicles on Chinese roads by 2020, serviced by over a thousand hydrogen refuelling stations," he says.

To that end, Beijing has reduced subsidies to the battery sector and, in 2018 alone, invested $12.5bn on fuel cell technology and related subsidies.

While Japan's commitment is relatively modest - a mere 800,000 new hydrogen vehicles - we can expect to see a big showcase of hydrogen technology at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics.

And South Korea's President Moon Jae-in has endorsed a big expansion of the country's hydrogen refuelling infrastructure to 660 pumps by 2030.

If these ambitions are even half-way realised, the rest of the world will be playing catch-up.

You can listen to Fergus Nicoll's report on hydrogen-powered cars on World Business Report here.