How the scramble for sand is destroying the Mekong

- Published

Desert sand is too smooth to bind to make concrete, so sand is taken from river beds such as the Mekong

A crisis is engulfing the Mekong River, its banks are collapsing and half a million people are at risk of losing their homes.

The entire ecosystem of this South East Asian river is under threat, all because of the world's insatiable demand for sand.

Extracted from the bed of this giant river in Cambodia and Vietnam, sand is one of the Earth's most sought-after resources. Up to 50 billion tonnes are dredged globally every year - the largest extractive industry on the planet.

"Extraction is happening at absolutely astronomical rates, we're having an industrial-scale transformation of the shape of the planet," says river scientist Prof Stephen Darby at Southampton University.

His studies on the lower Mekong show its bed has been lowered by several metres in just a few years, over many hundreds of kilometres, all in the quest for sand.

From highways to hospitals, sand is the essential component for industries as varied as cosmetics, fertilisers and steel production - and particularly for cement.

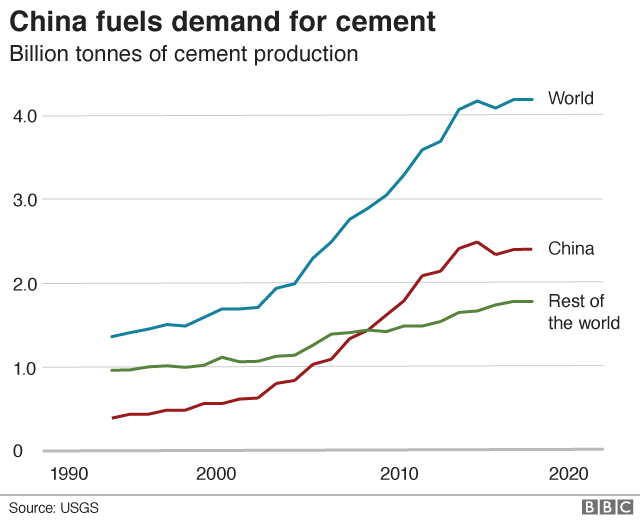

In the last two decades demand has increased threefold, says the UN, fuelled by the race to build new towns and cities.

China consumed more sand between 2011 and 2013 than the US did in all of the 20th Century, as it urbanised its rural areas.

Sand is also used to bulk up landmass - Singapore is 20% bigger now than it was at the time of independence in 1965.

"Every year we extract enough sand to build a wall 27m (89ft) high and 27m wide, all the way around the world," says Pascal Peduzzi of the United Nations Environment Programme.

China's construction boom has led global demand for sand

Not any old sand will do. Desert sand is too smooth and fine to make concrete. Nor is it the kind that is needed to make glass or be used in the electronic industry.

So that is why sand is sought from ancient deposits in quarries - static extraction - or through so-called dynamic extraction from the sea and rivers like the Mekong.

Mr Peduzzi says dynamic extraction can be particularly damaging: "The sand is part of the ecosystem and plays a vital role, which if lost effects biodiversity, erosion and increases salinisation."

The Mekong river runs through six countries

According to conservation charity WWF and the Mekong River Commission, the bed of the two main channels of Mekong Delta lost 1.4m in elevation in the 10 years to 2008, and between two and three metres have been lost in elevation since 1990.

Research in Nature, external, published last month, says that the sand mining on one 20km (12.5 mile) stretch of the river is "non-sustainable" as it cannot be replaced fast enough by natural sediment from the river's upper reaches.

It is not just a threat to the humans. The Mekong supports the world's largest inland fishery, providing a food source for the 60 million people living in the catchment area. The WWF reckons 800 species of fish and one of the largest remaining populations of the endangered Irrawaddy dolphin, live there.

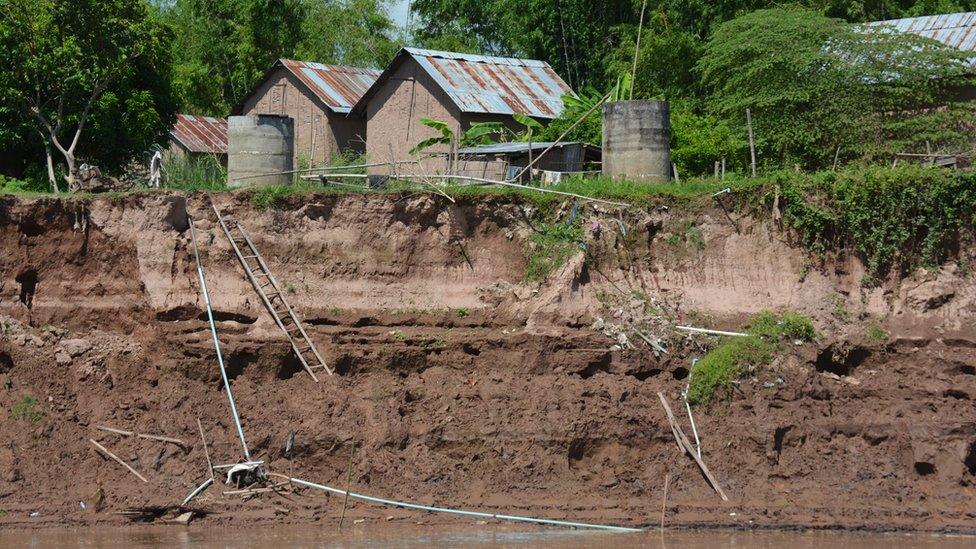

The removal of sand from the Mekong has caused erosion

The Mekong is not the only place where the grab for sand is creating controversy. In Kenya and India for example, there have been violent clashes over the resource, which is consumed at a rate of 18kg for every person on the planet each day.

So is the world running out of sand? Mark Russell, director of the UK Mineral Products Association, says it is not so much about running out, but reliance on harder to find sand.

"While this is a global issue it is playing out at a local scale, it is a resource no one really thinks about," he says.

One way to tackle the issue is by looking at ways to use the world's abundant desert sand. Scientists from Imperial College London have taken smooth desert sand and developed a building material which they have called "Finite". It has the same strength as residential concrete, with half the carbon footprint, and unlike concrete it is biodegradable.

Global Trade

At the same time, limits to supply of river sand are being put in place. Vietnam and Cambodia officially banned sand exports from the Mekong River in 2009 and 2017, respectively.

Yet on the internet, Mekong River sand is advertised in orders from 20,000 to 200,000 tonnes. And Rolf Aalto, a geography professor at Exeter University, has found that while Cambodia claims not to be exporting, Singapore continues to record imports from the country.

The Cambodian Foreign Ministry for Mines and Energy did not respond to the BBC's request for comment.

But the situation illustrates what Mr Russell describes as a global absence of transparency. "If you don't actually know what you're consuming or where its coming from or going, it's incredibly difficult to take informed management decisions."

Vietnam and Cambodia have officially banned Mekong sand exports but sand from the river is still for sale on the internet

There is a lack of data, Prof Darby agrees. "The major difficulty with sand mining is that the lack of governance tends to mean that there is not any systematic data on the extent and magnitude of the trade globally."

Mr Peduzzi says this is why a world monitoring centre is needed. "At the moment all we have are general estimates and we need to centralise our efforts."

That is in addition to the resolution on mineral resource governance outlined by the UN in March,, external which stipulates how countries should reduce the impact of sand mining.

"We just need to be much more clever in how we use it," says Mr Peduzzi. "Sand has to be recognised as a strategic material, not just an endless supply."