'My job went abroad because of globalisation'

- Published

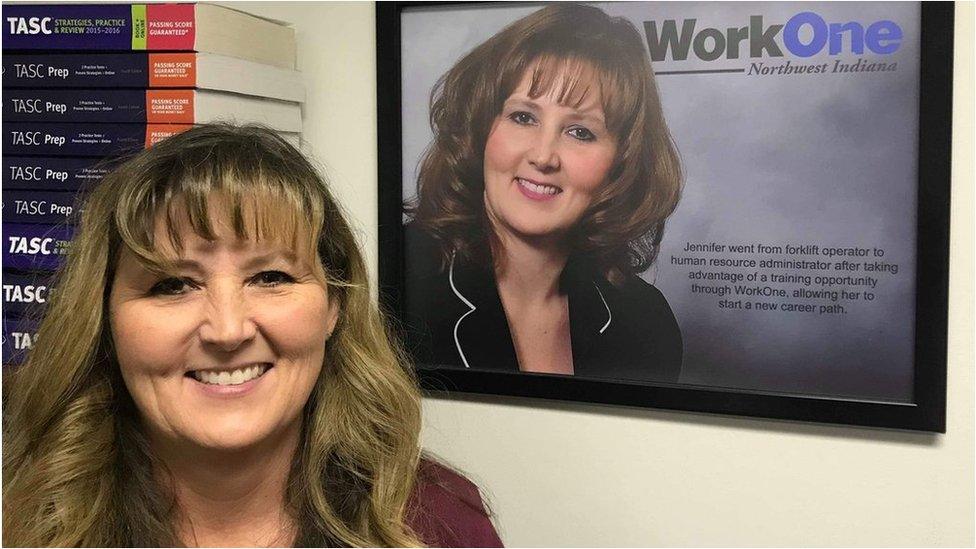

Jennifer Honn stands next to a poster detailing her success story at her local employment office

When Jennifer Honn lost her job as a forklift truck driver in Kentland, Indiana, she knew where the blame lay.

In 2005 her employer, food packaging company Viskase, moved its factory to Mexico.

"A lot of factories and jobs like mine went out of America to other countries after the Nafta [North American Free Trade Agreement] deal was signed," she says.

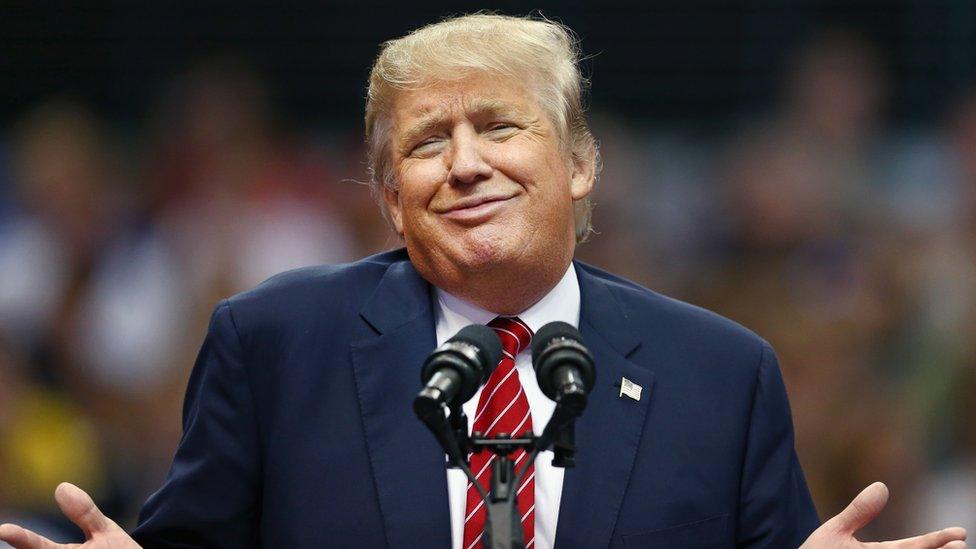

President Donald Trump has also long said that the 1994 agreement between the US, Canada and Mexico was the cause of such factory transfers, and resulting job losses like Ms Honn's.

As a result, he last month signed a replacement deal called the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement, which is set to come into force as soon as Canada ratifies it. It remains to be seen whether this will keep more jobs in the US.

Nonetheless, his decision to rip up existing trade deals - be they with America's neighbours, the EU or China - has reignited the debate over how to help those left behind by globalisation.

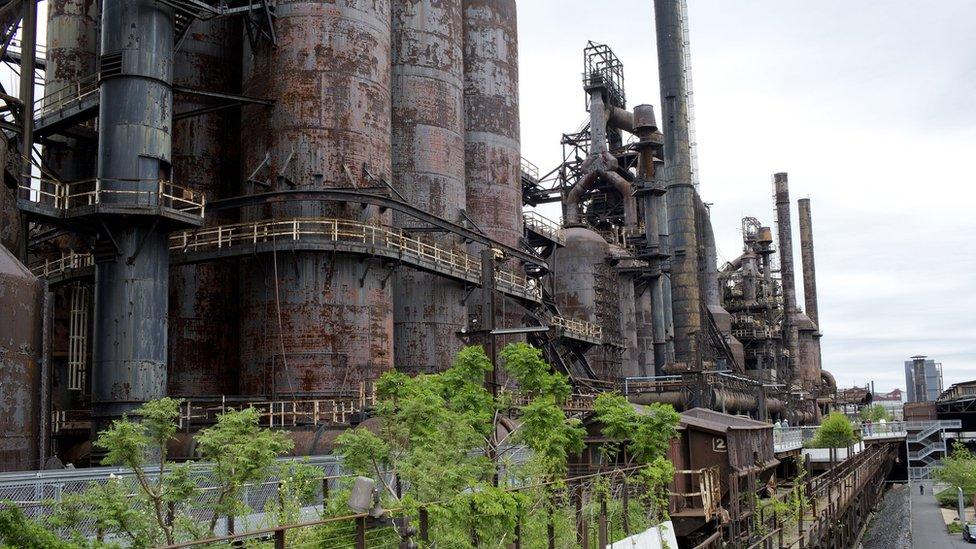

The US has lost plenty of heavy industry in recent decades

What is less well-known is that in both the US and the EU, help is already at hand for workers who have lost their jobs as a result of factory closures caused by global market forces.

In the US, financial aid for those who lost their jobs because of foreign competition has been available since the 1960s through a programme called Trade Adjustment Assistance (TAA).

Workers can get up to three years of unemployment benefits, and help to start a new career, such as government grants to retrain. In 2018, there were 76,902 people who qualified for the $800m (£618m) a year programme.

Ms Honn, 47, accessed the scheme back in 2005 to spend two years studying business management.

She says free tuition was a huge benefit at a time when her two daughters were aged just six and nine. After Ms Honn graduated, she got a job at a pharmacy.

"If I didn't go back to school I'd probably still be in a dead-end factory job or something in retail," she says.

US President Donald Trump's trade wars and demands for new agreements are ripping up old rules

The EU started a similar scheme in 2006 called the European Globalisation Adjustment Fund (EGF). In the past five years, hundreds of millions of euros have helped workers at Air France, external, Carrefour in Belgium, external and Sweden's Volvo, external to find new work.

Among other things, the money has been spent on training, careers advice and help for people setting up their own business.

Kirsi Junnilainen got help from the scheme in 2012, when telecoms giant Nokia decided to close a big factory in Salo, south west Finland.

Ms Junnilainen had worked there for 16 years, rising from the assembly line to supervisor. The strain on a town of just of 50,000 people was immense, she says.

"Fortunately my husband was working, and my children were already teenagers. But many people were forced to sell their homes."

Unlike in the US, applications for funding are led by EU member states, not workers or companies. Countries submit a plan and can ask for up to 60% of the total cost of a back-to-work programme. So far 21 nations have accessed the fund, but the UK - which has now left the EU - was not one of them.

The European Commission, which assess applications, said the unemployment rate in Salo would have jumped from 6% to 17% if nothing was done.

Kirsi Junnilainen (right) is now earning more money than she did at Nokia

With the help of EGF money, Ms Junnilainen was able to stay in work - initially helping her former colleagues to find new jobs - before she found employment at an IT consultancy.

"For those who started training programmes it was also really important, especially for those who were a bit older," she says. "If they had nowhere to go everyday they may not have returned to work for years."

While initiatives like these have helped tens of thousands of people on both sides of the Atlantic, Ms Junnilainen says EGF's focus on big companies created tension in her town.

"It would have been good if the scheme helped other companies in our town that were affected by the downturn, not just Nokia. People felt that if you weren't working for Nokia then you weren't worthy."

The EU is listening. Next year, if 250 jobs are being cut in any company, workers will be considered for the aid, down from a threshold of 500. Jobs lost to automation could soon be covered by the programme too, as might firms affected by the UK leaving the EU.

The Nokia plant in Salo, south-west Finland, was a major employer in the town

Back in the US, data published by the US Department of Labor, external suggests that TAA has not been a universal success. In 2018, 22% of those helped failed to find a job within six months.

And while most workers under 40 end up with higher pay compared with their old jobs, those over 60 earn just under two thirds of their previous salaries.

Jennifer Honn says that after finishing her degree, she took a 10% pay cut, though she says her qualifications mean she now earns double what she did at the factory.

Ms Junnilainen also admits the adjustment was tough. "My monthly pay went down by thousands of euros," she says. But she too is now earning more than from her old job.

Esther Duflo, the Nobel prize-winning economist, has long argued that TAA funding is too small to have a meaningful impact in the US.

Global Trade

And Penny Goldberg, chief economist of the World Bank, thinks governments should be ploughing money into whole communities rather than handing it to individuals.

"Traditionally, these policies are viewed with great suspicion by economists," she says.

"But it's entire regions, entire communities that are affected by these issues, and that calls for policies that address the challenges that these communities face."

Ms Junnilainen is in no doubt about the benefits of the European scheme.

"I remember seeing one lady who used to work on the production line now driving a bus.

"The money she was earning was coming back to the community because she was able to keep working. I remember she was so happy, and that's why I will carry this programme with me for the rest of my life."

- Published19 January 2020