What sort of future does the conference industry have?

- Published

Virtual reality is likely to play a bigger role in future conferences

"I'm devastated," says Mike Walker, managing director of MGN Events.

The company went from generating millions of pounds in revenue to near zero in just weeks, because of lockdowns.

"Over 10 years of hard work building the company up from nothing, reinvesting each year for growth, taken away cruelly in the space of a couple of weeks, with no clarity on when the industry can resume," Mr Walker says.

Thousands of others in the events industry will be facing the same uncertainty. The pandemic has completely shattered a huge sector, and many businesses are struggling to survive. According to a 2018 report, business events alone are a $1.5 trillion (£1.2tn) industry globally.

That's without considering the huge number of consumer events, exhibitions, experiences and weddings.

Mike Walker saw the income of his events firm wiped out due to coronavirus

All of these events rely on people turning up in person, and that is not currently possible with some venues closed or at a reduced capacity, and with travel restrictions in place - not to mention various other safety precautions required at the venue itself.

"Even if you hold an event in a larger venue, if you have delegates flying in and staying in the hotel, and one person tests positive for Covid-19, then you're going to get a call from the hotel telling you they're going to have to give the venue a deep clean and shut it down," says Steve Parrott, co-founder of Alternative Events.

'We need a date to restart so we can save our staff'

That kind of scenario is why companies are being forced to look at technology as the alternative, with virtual events becoming the norm throughout lockdown.

Most businesses have turned to technology that has become familiar for many people - video conferencing software from Zoom or MS Teams.

However, these technologies were around before the pandemic, and while they offer an alternative, they do not provide the same level of engagement as physical events.

Paddy Cosgrave says networking opportunities need to be built into new conference technology

"Most of the platforms for virtual conferences are built by third-party providers that don't organise events," says Paddy Cosgrave, co-founder of Web Summit, one of the biggest tech conferences in the world.

As video conferencing tools have been built for the mass market, rather than for specific industries, event organisers and sponsors are scrambling around for an alternative.

One option, taken up by The Moodie Davitt Report and retail marketing and design company FILTR, has been to bring together existing products into one system.

"We looked at the software that exists in the industry and we didn't think any of them would be sufficient to attract the brands we needed to attract," says Martin Moodie, founder of The Moodie Davitt Report, a publication that focuses on travel retailing.

Using existing software it creates a virtual version of a physical event - enabling people to walk around and view the different stands and communicate with brands by speaking to people in a chat format, all from their laptop.

The company integrates this with web-conferencing capabilities and meeting scheduling software.

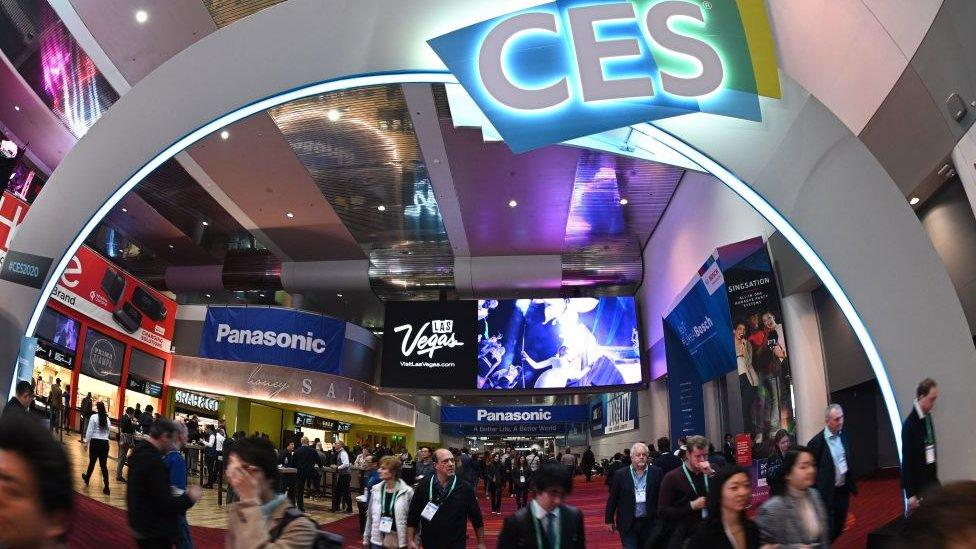

CES attracted around 170,000 visitors this year

But for some of the larger conferences, even integrating these products isn't necessarily enough. The Consumer Electronics Show (CES), which welcomes 170,000 delegates to Las Vegas every year, is going ahead with its 2021 event in January.

Jean Foster, senior vice president of marketing and communications at the Consumer Trade Association, which runs the event, says that the organisation is creating its own digital platform for CES as it expects that turnout will be lower as a result of the virus, and it is therefore switching to a hybrid offering.

"We're working on what that platform is going to look like... there's nothing off-the-shelf of the scale and capabilities we need," Ms Foster says.

Web Summit has also created a platform from scratch. Mr Cosgrave says that for most business events, networking is the key reason that people attend. It is also critical to the success of an event, as sponsors can communicate directly with their target audience.

Crowded stands are on hold

Mr Cosgrave's team had already worked on trying to engineer serendipity into the physical Web Summit event, by seating people next to others who may have mutual interests. Now that the event, held in Lisbon in December, will be at least partly online, his team have been working on allowing that serendipity to also flow into an online environment.

The company takes information, with consent, from social media and delegates' phone books to create an algorithm that matches people with others that they would likely find interesting or want to talk to.

"Delegates will see the people that are recommended to them, while other people are seeing them in a very personalised way," he says.

"On the platform, they can do one-to-one video calls with one another, they could do group calls with each other, or you could start a group video chat and invite people, or join Q&As with speakers, for example."

With Box Bear technology users get their own avatar

Some technology companies see a gap in the market to help enable attendees to have more control during an event.

Box Bear Digital supplies virtual reality (VR) headsets to clients who can then distribute them among delegates. The headsets have to be returned after the conference is finished.

During the VR conference, attendees are represented by their own real-life avatars. Users can take notes on slides, get certain quotes transcribed and sent to email, zoom in, change their viewpoint, and interact with virtual elements.

"The key difference is being fully immersed and engaged, there's no escape as soon as you put the headset on," says Graham Addison, global marketing director of pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca, which has tested out the technology.

The added value provided to the organisers, according to Box Bear Digital, is that they have a better idea of what the audience is doing, as the technology can track whether the person is shaking their head, or raising their hand to ask a question.

Generally, event organisers don't stand to make the same amount of revenue in a virtual alternative. However, there are numerous benefits to holding virtual events.

Virtual events are far cheaper to run, and at a time when companies are more conscious about the environment, they offer a sustainable alternative to flying people in from across the world. In addition, they give the organisers the ability to get viewers from across the world, on different timezones, to tune in, and potentially attract better speakers for the event too, as they don't need to travel.

There is also more scope to measure outcomes.

"We can constantly tell those people putting on the event how many people were engaged, how many visitors they had, how many people downloaded their content - you can't measure this in the same way for a physical event," says Mr Walker.

Despite this, many event organisers can only see the use of these virtual events as a stop gap, or as part of an overall hybrid event in the future. Perhaps this is why the likes of Microsoft and Zoom haven't moved quickly to provide new features for their platforms.

"Four months into lockdown, why is there nothing new on the market? Perhaps digital [events] aren't worth investing in because although they will be a part of the mix, they won't be the main part of the event, because people think we'll be returning to normal soon," says Mr Parrott.