Why the humble text message is a key campaign tool

- Published

Campaigning apps allow contact to continue after an election

"I spend a lot of time doing Zoom town halls," says Melissa Watson, a schoolteacher and army veteran standing for Congress in South Carolina.

Her district is mostly rural, and pandemic restrictions have limited her ability to knock on doors.

South Carolina shut down non-essential businesses on 1 April, and then implemented a state-wide home-or-work order on 7 April. Apart from a few exceptions, like necessary shopping or outdoor exercise, residents had to stay at home unless they were working.

So, Ms Watson joins Zoom meetings with local groups and county parties. "Whatever anybody will invite me to," she jokes.

Meetings with female politicians and businesswomen, which she calls "Women, Wine, and Watson" are among her favourite Zoom gatherings.

Melissa Watson is running for Congress

Ms Watson uses a host of different apps to support her campaigning, She lists seven for me, including apps that analyse data and two different text messaging services.

It may seem strange that the humble text message - the old-fashioned SMS, not even WhatsApp - has emerged as the workhorse of the 2020 US election.

By some estimates one billion text messages will have been sent in this US campaign cycle. That is at least double, and perhaps triple, the volume of texts sent in previous campaigns, says Jay Godfrey, vice president of NationBuilder, a leading campaign software firm in Los Angeles.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The reason for that deluge is that people pay attention to texts.

According to research company Gartner, 70-98% of text messages are actually read, compared with 20% of emails and people respond to 40-50% of texts, but only 6% of emails.

Email "is dying a slow and painful death," says Daniel Serralde, chief of staff for the Dallas county Republican party.

Messaging apps like Hustle, GetThru, and RumbleUp let campaign volunteers first message their close networks, then their neighbours and others in their vicinity.

They are designed for elections: Hustle for political campaigns and non-profit organisations, GetThru targeting the Democratic side, and RumbleUp aiming at the Republican end.

These apps, or versions of them, are designed to go into the hands of party supporters, to help them contact people they know.

Recipients can reply, since there's a human volunteer on the end, and ask questions about voting locations, postal ballots or Zoom meetings.

Email is on its way out according to Daniel Serralde, chief of staff for the Dallas county Republican party

There's also the option of cross-referencing a volunteer's own contacts with target lists of supporters or undecided voters.

"Actually the most effective voice to get someone to go out and participate is their sister, co-worker or mum," says Mr Godfrey.

And when your sister sends you a link, perhaps for a Zoom town hall meeting or a petition, and you click on it, the campaign will know it was her link you clicked.

That means campaigns can "see, acknowledge, and thank people who are really enthusiastic," says Mr Godfrey.

It's a change for the better, argues Brendan Tobin, vice president of Ecanvasser, a campaign software company founded in Ireland which now works internationally.

"It's more relational, it's more real and sustainable, and political parties don't lose these people post election," he says.

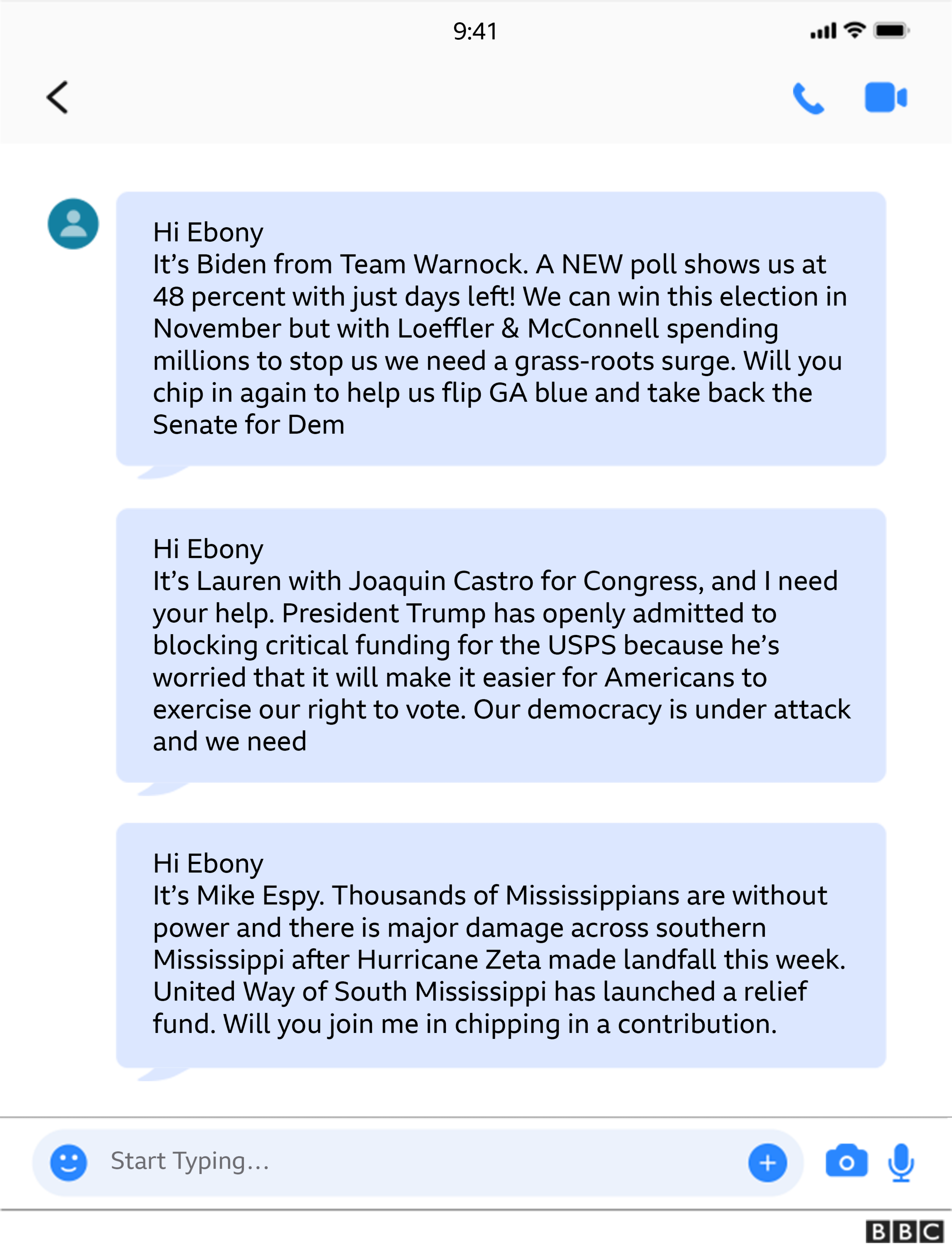

These are just three of the texts one voter received

Like much of the new 2020 campaign technology, these apps are inexpensive and can create a more level playing field for poorer candidates and non-traditional voices, who might otherwise be excluded.

The Lincoln Project, a group of prominent Republicans opposing Donald Trump's re-election, is an example.

Peer-to-peer messaging and social media placed them in the spotlight.

"That kind of group wouldn't be getting as much traction traditionally. They're a major player despite being shunned by their own party which is pretty astonishing," Mr Godfrey says.

Messaging systems are "more real" says Jay Godfrey, vice president of NationBuilder

As for television, campaigns used to buy huge amounts of advertising around local TV programming and hope for the best.

But now, it's possible to aim a particular advert to a specific television viewer.

That's because many modern cable boxes are "addressable", which means they have an individually identifiable serial number built into their microprocessor. So cable TV firms can tailor advertisements to particular households and they sell that service to campaigns.

Ten years ago this technique was only available in the biggest urban areas, but is now available in every state.

Early in an election, campaigns can aim at undecided voters, then closer to election day, target their supporters who may need extra encouraging to vote.

Facebook is another avenue for campaigns looking to find particular voters. "We did a lot of Facebook ads," says Ms Watson.

"We tried everything to see what was going to give us the biggest bang for the buck, and Facebook ads probably was the most successful for us," she explains.

Facebook is important to election campaigns

Facebook lets candidates and other advertisers target users by postal code, education, income, age, job, gender, or if you've interacted with their Instagram account.

In fact Facebook allows advertisers to dice the population almost any way they like, perhaps finding people who have recently got engaged, had children, speak Spanish - or those who like vintage jazz pages or honky-tonk.

And if you're a candidate and have a list of at least 20 particular people, you can upload their email addresses or mobile phone numbers as a Facebook Custom Audience.

There's also a bit of code called Facebook Pixel that tracks which users click from Facebook ads to advertisers' sites, and makes it easier for advertisers to hone in on exactly who's clicking.

However, there is a danger that such narrowly targeted political messages swamp core supporters.

This high volume of contact "is naturally starting to tiptoe up to the irritating," warns Mr Godfrey.

The danger is you are turning people off because multiple organisations are contacting the same voter.

Also, when you get to this level of precision, "you get blinders and start to hyper-focus and leave out the art of politics, crafting the broader appealing message," says Michael Frias, chief executive of Washington DC-based Catalist, a data utility for political groups.

And here is a sobering thought; spending on the 2020 US election is set to reach $10.8bn (£8.3bn), says the non-partisan Center for Responsive Politics.

Yet a 2017 study from the University of California, Berkeley, external suggests the effect of all this money and campaigning on voters' candidate choices is, to quote the authors - "zero".