Goodbye ATMs. How local shops offer access to cash

- Published

One of the cashback trials is being run in Imran Hamid's shop in Denny, a few miles west of Falkirk

Step into a shop, demand cash from the till, then walk out without buying anything: it sounds more like theft than a government-approved activity.

Yet purchase-free cashback at local convenience stores is being touted as one solution to the problem of disappearing access to notes and coins.

Millions of people - including the elderly, those without internet access, and some of the poorest in society - face being left behind in an increasingly cashless UK.

The Covid crisis has accelerated the closure of bank branches and ATMs, especially in small, more rural or isolated communities where access to cash is getting harder.

'They've all shut'

One of those areas is Denny, a small town west of Falkirk.

"Denny is a town where we used to have a TSB, a Royal Bank of Scotland, a Bank of Scotland, a Clydesdale Bank. They've all shut," says Imran Hamid, whose family has run a convenience store in the town for 50 years.

His is one of a small group of shops around the country trialling the no-purchase cashback scheme.

The PayPoint machine in Imran Hamid's shop

Residents can come in, put their card in a PayPoint machine and request a balance or cash from Mr Hamid's till, without paying any charge.

Despite some initial confusion, he says the service is being used a lot.

The advantage to the business is that people coming into the shop to withdraw cash may also "pick up a juice, or a pack of cigarettes". Mr Hamid gets a small fee from the banks per withdrawal and it makes cashing up easier at the end of the day.

But the 45-year-old says it is the public service that makes him an enthusiastic participant, helping the elderly residents who have known him since he was in a nappy.

"I think it's just a community thing where we try to help and give back something," he says.

"We've also got people who are on benefits here. They want access to their cash. That's another good thing about this - they can withdraw anything from a penny to £100.

"If someone on benefits has only got £3.50 left in their bank account and they want that £3.50, I can give them that £3.50 and it is not going to cost them anything."

Unlike ATMs, these cashback trials mean people are not restricted to withdrawing multiples of £5, £10 or £20 notes. The average withdrawal is £26.80, about a third of the typical cash machine withdrawal.

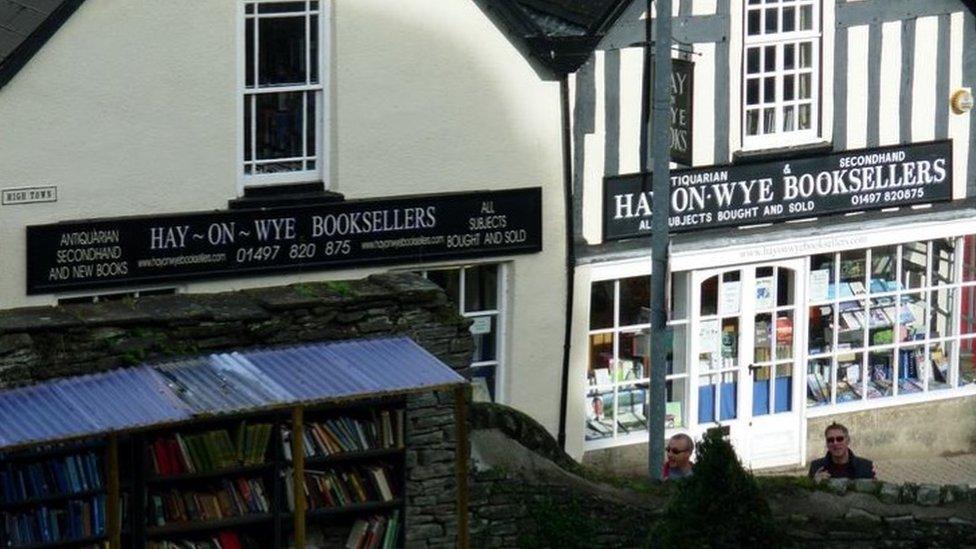

The Covid crisis means contactless payments have been used more

But some shops are still keen to accept cash

Mr Hamid's store is one of 13 small shops in four communities across the UK taking part in the programme that is supported by Link, which oversees the UK's cash machine network.

They are part of a wider set of tests in eight cash-stricken communities across the UK. Other trials include a financial hub in a Methodist church and drop-and-go deposit points for small firms.

Link has been heavily criticised by those who see it as being part of the problem, for cutting the fees it pays to cash machine operators.

Adrian Roberts, chief commercial officer at Link, argues that the reality is that as few as one in 30 transactions could be made in cash in a few years' time.

Of the UK's 42,000 free-to-use cash machines, many located in High Streets, supermarkets and city centres will survive, but many in quieter areas will not be commercially viable, he says.

That outlook may come sooner than expected owing to Covid.

There are currently 42,000 free-to-use cash machines in the UK

From April to September, the number of cash withdrawals from ATMs - a good indicator of cash use - dropped dramatically, by as much as 81% in central London compared with the same period a year earlier and by around 70% in Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Admittedly, people were not going out much, but Link's own survey suggested that three-quarters of those asked would continue their Covid-related cut in cash use into the future.

In August - as many people "ate out to help out" - nearly two-thirds of debit card transactions were contactless, a record level.

That too may be understandable owing to the virus, but it also reflected a change in attitudes and the rise in the contactless limit from £30 to £45 in April.

'New laws needed'

If cash use falls enough, so the business of transporting it, sorting it and managing it becomes untenable. The first to see the effect are those more isolated communities. Hence these trials designed to protect the residents who need it the most.

Any expansion of the convenience store cashback scheme will need legislation, and the government has already signalled its support.

A consultation on access to cash ends on Wednesday, and follows a highly critical report by the National Audit Office on the "fragmented" response to disappearing cash access by the various authorities involved.

But Natalie Ceeney, who wrote the landmark Access to Cash Review, external, which warned about the dangers of a cashless society, says law changes need to go further.

She is calling for a legal obligation on banks to make sure their customers can get and use cash if they need it.

"Everybody needs the ability to pay for things - just as they need the ability to use post offices or water or electricity," she says.

"My fear is that the coronavirus has made the cash infrastructure even more vulnerable. As we start to emerge, more ATMs will close, more bank branches will close, and more bits of the UK will be left without cash. We need legislation quickly."

How quickly?

"Now," she says.

- Published15 October 2020

- Published23 September 2020

- Published18 September 2020

- Published17 June 2020