UK borrowing hits highest November level on record

- Published

- comments

Government borrowing soared in November as the UK continued to support the economy during the coronavirus pandemic.

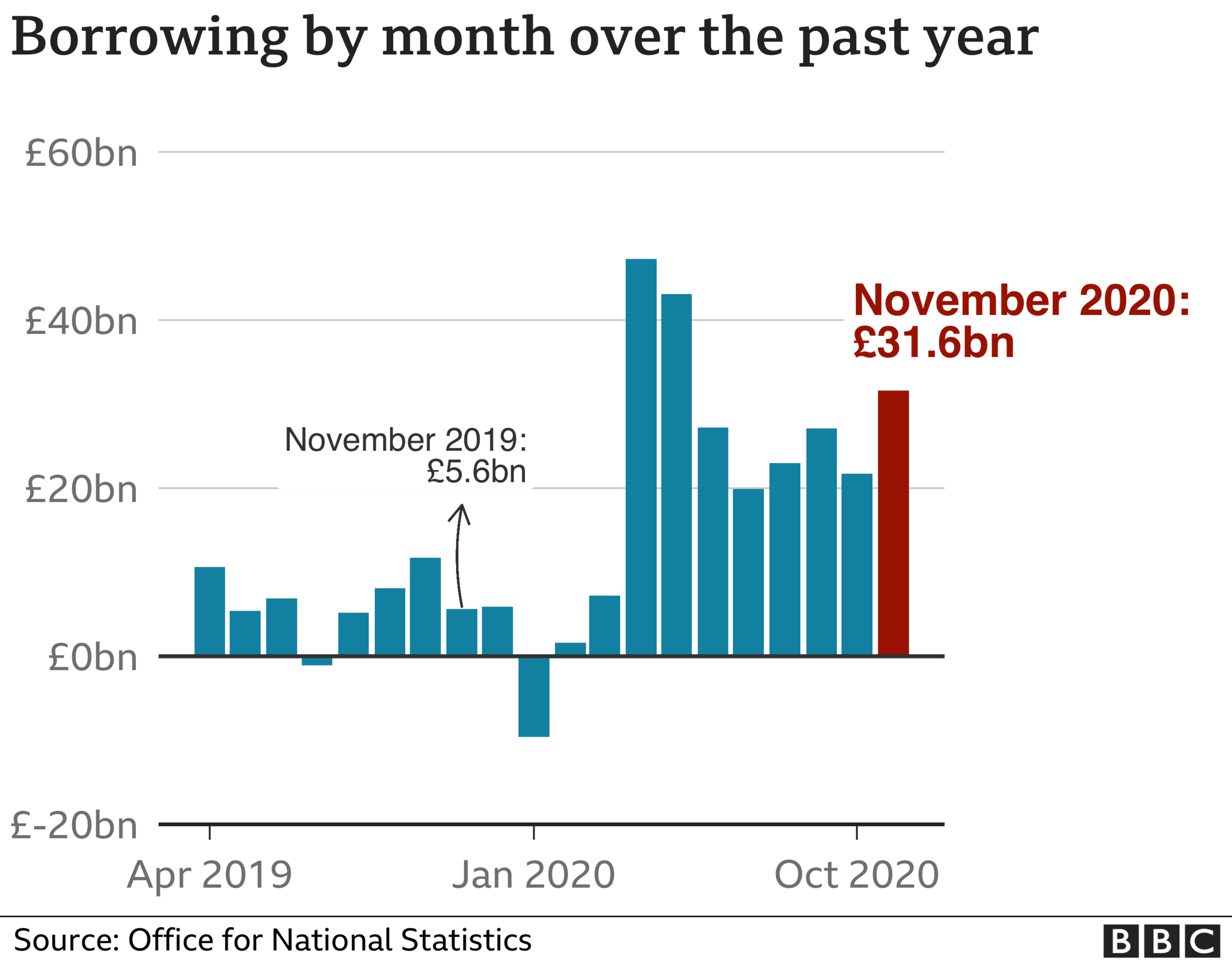

The Office for National Statistics said, external borrowing hit £31.6bn last month, the highest November figure on record.

It was also the third-highest figure in any month since records began in 1993.

The figures highlight the government's spending-revenue gap, and underline Chancellor Rishi Sunak's problems as he weighs up bolstering Treasury coffers.

Since the beginning of the financial year in April, borrowing has reached £240.9bn, £188.6bn more than a year ago, the ONS said.

A Budget had been expected to take place in autumn this year, but it was delayed because of the pandemic and will now take place on 3 March 2021.

The independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has estimated that borrowing could reach £372.2bn by the end of the financial year in March.

However, Mr Sunak made clear on Tuesday that he would not be taking any hasty action. "When our economy recovers, it's right that we take the necessary steps to put the public finances on a more sustainable footing so we are able to respond to future crises in the way we have done this year," he said.

Mr Sunak has already imposed a pay freeze on at least 1.3 million public sector workers as part of efforts to contain government spending.

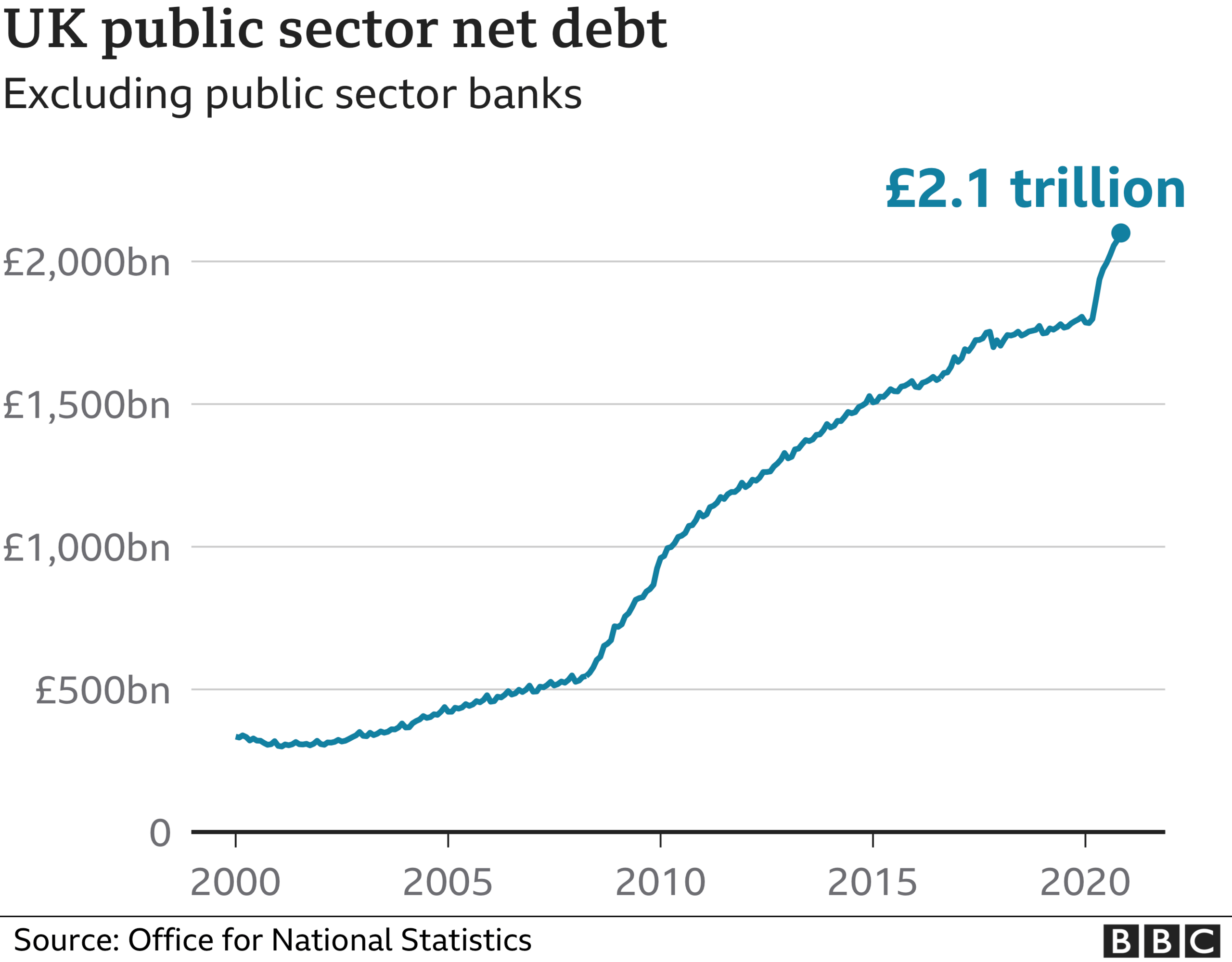

The increase in borrowing has led to a steep increase in the national debt, which now stands at just under £2.1 trillion.

The UK's overall debt has now reached 99.5% of gross domestic product (GDP) - a level not seen since the early 1960s.

Where does the government borrow?

The government borrows in the financial markets, by selling bonds.

A bond is a promise to make payments to whoever holds it on certain dates. There is a large payment on the final date - in effect, the repayment.

The buyers of these bonds, or "gilts", are mainly financial institutions, like pension funds, investment funds, banks and insurance companies. Private savers also buy some.

You can read more here about how countries borrow money.

"We are looking at the highest peacetime deficit and if we look at where the country's debt is, then we are at the highest levels since the 1960s," said Sarah Hewin, chief economist at Standard Chartered.

"In November alone, borrowing was about six times what it was in November last year, so these are some absolutely record numbers that we are seeing.

"Also, of course, the furlough scheme has been extended, so that will increase government spending. We could well see the deficit for the financial year all the way up to 20% of GDP, so around £400bn."

Separately, the ONS has also revised its figures for the UK's economic growth, external this year.

The economy shrank a little less in the April-to-June period than previously indicated, by 18.8% instead of 19.8%.

And the rebound from July to September was a little bigger, with growth of 16% instead of 15.5%.

Ruth Gregory, senior UK economist at Capital Economics, said a double-dip recession was a clear possibility if the tier four Covid-19 restrictions were extended into 2021.

However, she said there was optimism that as long as vaccines were effective and widespread, GDP would "stage a strong rebound" in the second half of next year.

Double-dip recession?

The extraordinary pandemic shutdown borrowing numbers had begun to recover. But last month, as some restrictions were reapplied across the UK, the government borrowed £31.6bn, the third-highest month on record.

This was £26bn higher than last November, driven mainly by a £23bn increase in government spending on a year ago, including the reapplication of the full jobs wage subsidy furlough scheme.

Borrowing so far this financial year since April is already at a record £240bn and set to hit about £400bn over the full year.

Growth in the economy in the third quarter was a little higher than first calculated, at a record 16%, but that now is firmly old news.

The likely spread of new restrictions on retail and hospitality and multiple forms of chaos at ports mean forecasters fear the UK may already be back in a double-dip recession.

Related topics

- Published28 November 2019