Covid inequality: 'I struggled with the bills and my health'

- Published

Leonie has managed to bring her debts under control

Leonie's financial plight was precarious. She had £3,000 in rent arrears and was struggling to keep up with bills.

Her physical health was poor, which meant she was unable to work, and her mental health was a problem too.

"It was hard," says Leonie, who is in her 60s. "I lost a lot of weight. I was not eating."

Nearly 11 million UK adults had low financial resilience going into this pandemic, meaning they could not cope with a financial shock such as a £50 a month cut in their income.

People in this group were disproportionately likely to be just like Leonie: unemployed, renting, female, and black.

Then Covid struck, and suddenly there were a lot more Leonies.

The poor are more likely to die from the virus, and there is no vaccination to protect their financial well-being.

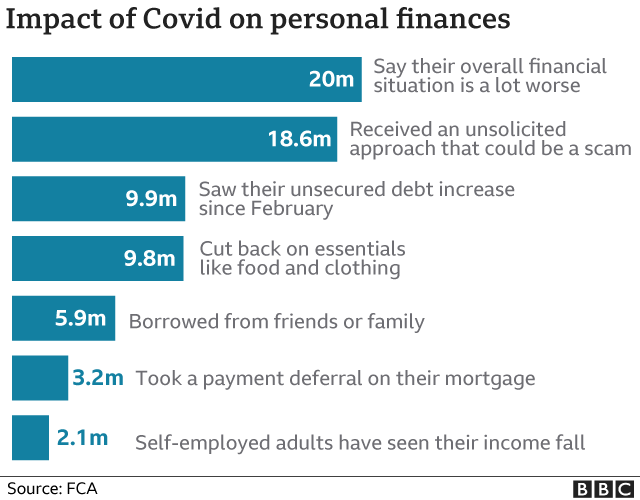

Another 3.5 million people found themselves on the financial precipice, according to a hefty piece of research by the Financial Conduct Authority, called Financial Lives, external.

By October, more than a quarter (27%) of UK adults had low financial resilience.

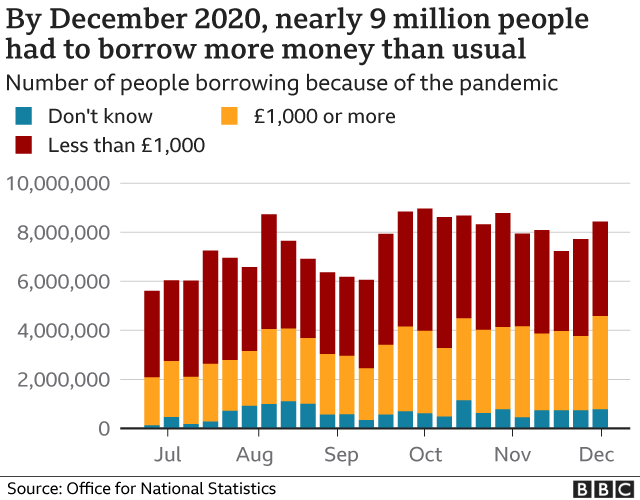

Many had lost their jobs, furlough had cut their income by a fifth, some had working hours reduced, and some were sick. They were in debt, had little in savings to cover their losses, and had bills to pay.

A survey by the Hope Not Hate charitable trust found that 22% of black, Asian and minority ethnic people it asked had lost jobs owing to the virus, compared with 13% of white respondents.

One of them is 41-year-old Moira (not her real name), who had been working as a cleaner.

"To lose my job was very difficult, because I was the breadwinner," she says.

During lockdowns, her three children - aged between 10 and 15 - have been at home.

"The heater has been on and there have been three meals to make each day. The bills were too much. I want to work, I do not want to be in debt," she says.

She has tried to find a job as a carer, so far without success. Applying for universal credit was hard, as English is not her first language.

Yet, Moira and Leonie, so typical in many ways, both did something unusual. They asked for help.

Jerry During from the social enterprise Money A+E says "inequality has been more exposed" by the pandemic

An estimated 8.5 million people had unmanageable debts by October, according to the FCA's Financial Lives survey.

Only 1.7 million of them had sought any kind of debt advice in the previous six months.

Why? Because most are too embarrassed, did not want to face the problem, or did not know free advice was available, the FCA says.

Jerry During, chief executive and co-founder of social enterprise Money A+E (Money Advice and Education, external), says the reasons are more complex.

Mental health is often an accompanying factor. Many, among diverse ethnic communities, have had a negative experience from the box-ticking conveyor belt of large debt advice services, he says.

His organisation hires advisers from the communities they serve, with the language skills needed, and who have lived through the experience of overwhelming debt themselves.

"Just giving them advice and sending them on their way is not going to help," he says.

In Newham in east London, where Money A+E operates, nearly two-thirds (64%) of adults told the FCA they would struggle to make ends meet during the six months from October - the second highest level of any area in the UK.

Mr During says "inequality has been more exposed" by the pandemic, although he praised some government policies such as furlough and extra money for universal credit claimants.

As that support is withdrawn, and life returns to some kind of normality, debts will remain.

Before the pandemic, Money A+E was helping people with debts of hundreds of pounds. Now the average amount owed is more than £10,000.

Leonie offers them hope. "He was a right bloke," she says admiringly of the adviser at the service who helped her get her debts back under control. "I'm a bit more up-to-date, and healthier too."

Many women have taken on the bulk of childcare in the past year

More widely, the longer-term effects on the income of women stepping away from work owing to childcare during the pandemic has been highlighted, following official statistics about the lockdown.

The financial recovery from the pandemic will be a very long journey for many families.

Inequality exists when there is an opposite experience.

Services for the wealthy have merely evolved, such as high-end restaurant delivery and online private tutors.

Stay at home and save

The big change during this pandemic though has been the increase in so-called accidental savers.

More than six million people's financial position has improved during the pandemic, according to a report by consultancy LCP.

It says more are benefiting than the FCA's research suggests, but both agree that older age groups are more likely to fall into this bracket.

Those aged over 55 had been most likely to save as a result of holidays being cancelled or not booked, and older people were also most likely to have cut back on eating out, the LCP report said.

Those holidays and restaurant trips have reduced for good reason - the older you are, the greater the risk of dying from the pandemic, so all the more reason to stay in.

Once again, physical and mental health are intertwined with financial health. None of them are easy to cure.

Related topics

- Published11 February 2021

- Published25 February 2021

- Published11 January 2021

- Published21 January 2021