The companies offering delivery to the Moon

- Published

Back in the 1990s Tim Crain assumed he would be working on missions to Mars

Not many people can say they have a doctorate in interplanetary navigation, but Tim Crain can.

While working on his PhD in Austin, Texas, in the 1990s he hoped one day to work on missions to Mars and in 2000 he landed his dream job with Nasa, at the Johnson Space Center in Houston.

"In 2000, the idea was, we would finish the space station in just a matter of years, and then the next big human spaceflight project would be to move on to Mars," he says.

But things didn't quite work out that way and shortly after he joined Nasa the agency's priorities changed.

"Things took a turn, we lost [the Space Shuttle] Columbia, had the global war on terrorism, so, Mars fell off the table," he explains.

He shifted to another Nasa programme called Constellation, an ambitious plan to return to the Moon and eventually Mars, but by 2010 it too had fallen by the wayside.

"I became a little bit disillusioned that the Moon was no longer an option with Nasa," says Mr Crain.

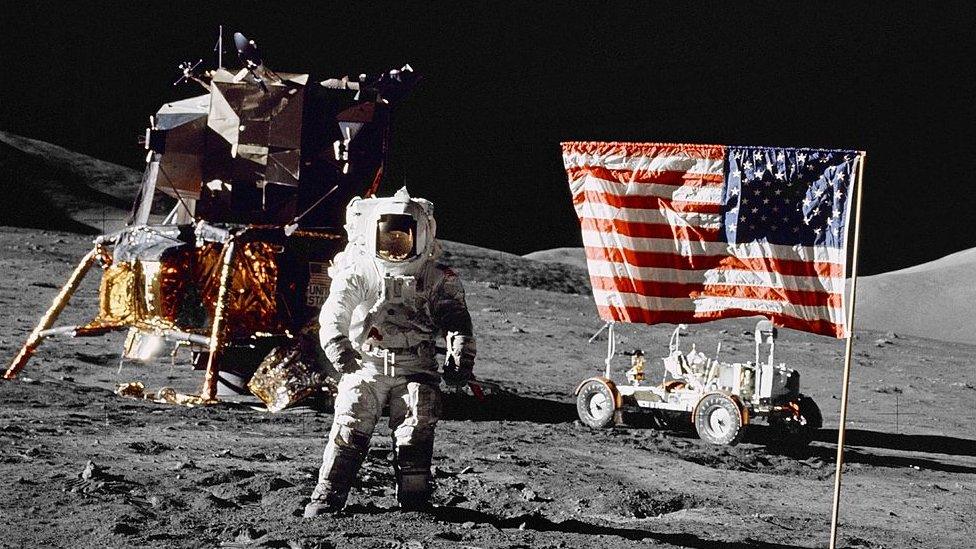

Apollo 17 was Nasa's final crewed mission to the moon in December 1972

So, after a decade with Nasa he left to form Intuitive Machines with co-founders Steve Altemus and Kam Ghaffarian.

Their plan was to apply their expertise to complicated engineering projects, which they did for a few years.

But in 2018 an opportunity came along that the partners could not resist.

In April of that year Nasa launched Commercial Lunar Payload Services, external (CLPS), a programme to commission private companies to take cargo to the Moon.

That cargo would include instruments and devices designed to pave the way for Artemis, Nasa's latest plan to return, external to the Moon, this time by 2025.

"We said: 'Hey, wait a minute. That's something we could go after,'" remembers Mr Crain.

So, they dropped everything and scrambled to get a proposal together.

"That was a new experience - to write a proposal for a lunar mission of 30 days. And we won, along with two of our competitors Astrobotic and Orbit Beyond and our lives changed," he says.

But winning the contract was only the first step, next came the design and development of a spacecraft that could get to the Moon.

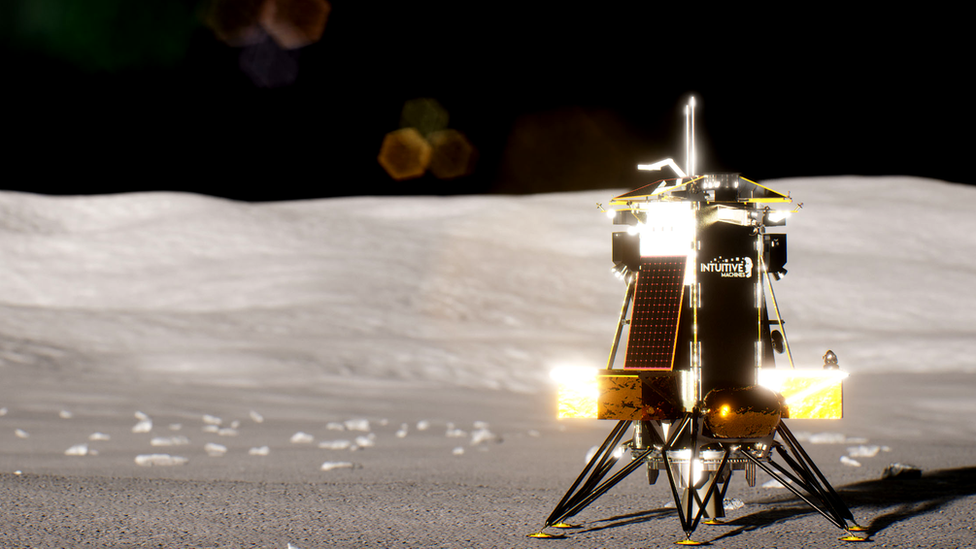

It took three years to build the Nova-C spacecraft

"We quickly discovered we needed to assemble a whole programme - we needed operations, we needed launch system integration, we needed an entire payload integration group.

"When you take that whole thing, we actually have a mini space programme," says Mr Crain.

Starting with nothing more than a blueprint it took Intuitive Machines three years to build their spacecraft, Nova-C.

Their engineers used knowledge of existing space technology and blended that with their own development.

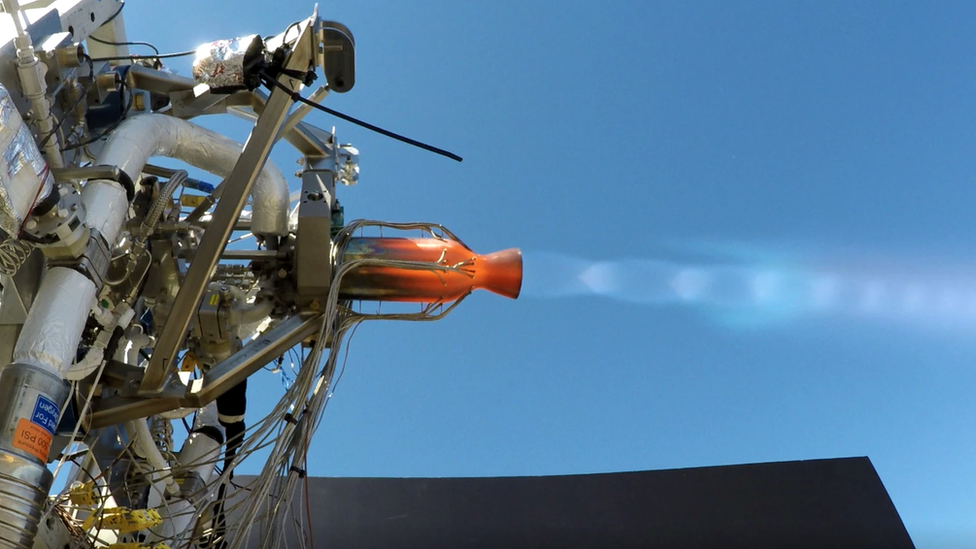

The company even developed its own propulsion system which uses methane and liquid oxygen, a well-tried combination.

Intuitive Machines developed its own engines

It is also a fuel that could, one day, be made in space to power future missions.

"Any place there's carbon and water, two of the most abundant chemicals in the universe, as far as we know. We'll be able to make methane."

"I think that LOX (liquid oxygen) and methane is the propulsion [system] that will drive commerce through the solar system," says Mr Crain.

The spacecraft, Nova-C is capable of transporting a payload of 130kg, but for its first flight is only carrying 80kg.

Mr Crain says that once Nova-C has proven itself, they will build bigger spacecraft. The company has plans for one that can carry a payload of five tonnes.

For Nova-C it is a four-day trip to the moon

But before those more ambitious missions, the first launch has to go to plan.

A US spacecraft has not made a soft landing on the Moon since the last of the Apollo missions in 1972. (The LCROSS mission in 2009 deliberately crashed a vehicle into the Moon to examine the material kicked up by the impact.)

Nova-C could change that when it blasts into space atop a SpaceX rocket in the first quarter of 2022.

It will decouple from that rocket after about 18 minutes and head to the Moon on a journey that will take about four days.

Once there Nova-C will enter a low lunar orbit for around 24 hours. Then it will use its main engine to brake for a soft touchdown between Mare Serenitatis and Mare Crisium, two of the dark lava seas on the Earth-facing side of the Moon.

Once safely down, it will operate for around 13 and a half days during the lunar day, during which time the Nasa and commercial payloads will be deployed and start work.

The experiments and data gained will be sent back to Earth using Intuitive Machines' own lunar data relay service.

Once it has run out of energy, everything shuts down and Nova-C will sit on the Moon's surface forever, or perhaps until some future astronaut comes along and recycles it.

The extreme conditions on the Moon present a huge engineering problem

One of the biggest engineering challenges has been managing the extreme temperatures that Nova-C will encounter on the Moon, where temperatures can be as high as 140C (284F) and fall to minus 170C (minus 275F).

"If it was just the spacecraft and its flight computers, that would be relatively easy. But now we have to take care of our payloads," says Mr Crain.

Heating and cooling systems have been designed to keep the cargo safe, even in the extreme environment of the Moon.

Simeon Barber is a senior research fellow at the Open University and has spent his career developing instruments that will work in space, on planets and other bodies including the moon.

His current project is a Exospheric Mass Spectrometer, which will head into space on the first mission of a rival to Intuitive Machines, Astrobotic. His device will analyse the composition of the lunar atmosphere around the lander.

Simeon Barber designs instruments that will work in space

"I think we are entering a new era, for sure," he says.

Previously, scientists like him might have worked on one or possibly two big space missions in their career, but now there are new possibilities with the prospect of more regular trips to the Moon.

"There are several missions on the slate now and this gives you the opportunity to do things quickly, to be a bit more risky, and not have all your eggs in one basket. So it kind of frees you from that fear of failure," he says.

Lunar transport systems from Intuitive and its rivals, as well as government-led programmes like Nasa's Artemis will be the start of a new era of human activity on the moon, says Mr Crain.

"Unlike the first time around, where we had to invent a lot of the technology from scratch, we have a lot of technology in terms of electronics, computers, manufacturing, and composite materials [that] has changed the game."

"I think within the next 20-30 years, you will see civilians paying for for trips to the Moon, for holidays.

"Predicting the future is hard, so maybe not. But I think it's feasible."

Dr Barber is cautiously optimistic. He highlights how hostile the Moon will be for humans, with the huge temperature range and lunar dust which, if not managed, will damage machinery and human lungs. He is also keen that further human exploration has a minimal environmental impact.

But would he go, if he could?

"I like my home comforts. But yeah. I think you'd have to say, yes wouldn't you?"

Follow Technology of Business editor Ben Morris on Twitter, external.