Is there a better way to make new resolutions stick?

- Published

Can apps make Padraig more productive?

"Run. Work on doctorate." So begin all my to-do lists but progress is elusive. With New Year's resolution season here - perhaps technology can make me into a more productive machine.

"An extraordinary amount of what we do is habit," says Brendan Kelly, professor of psychiatry at Trinity College Dublin.

It is estimated that between 45% and 95% of what we do is habitual, "but I'd reckon towards the higher end of that range," says Prof Kelly.

We act according to our habits, "from the time we rise and go through our morning routines, until we fall asleep after evening routines," says Ann Graybiel, a neuroscientist at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

We develop those habits by encoding them in a part of our brain called the striatum, which deals with reward and releases the "feel-good" neurotransmitter dopamine, her research shows.

Now a new cohort of apps - with names like SnapHabit, Habitica and Strides - reckon we can reprogram our habits to improve our lives and be happier.

An 'extraordinary' amount of what we do comes down to habit, says Brendan Kelly

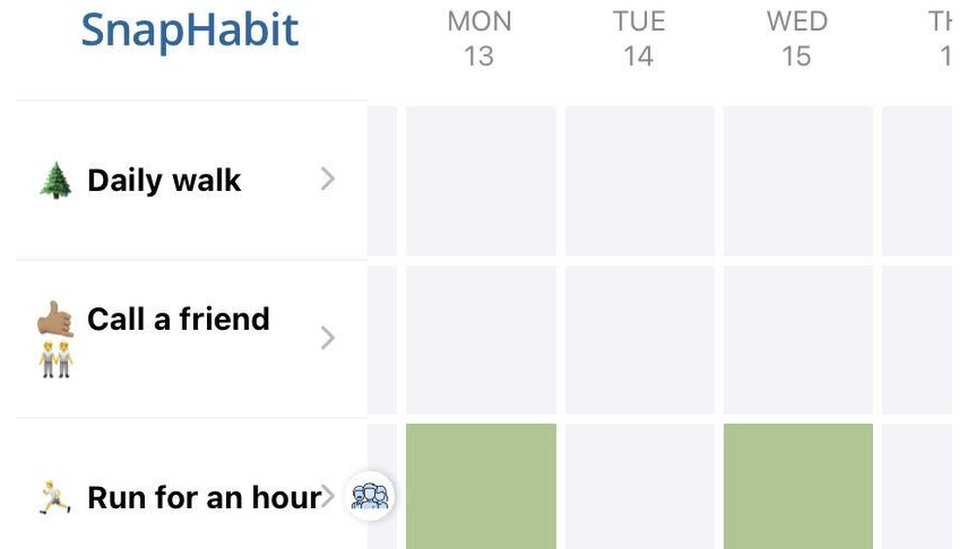

SnapHabit, for instance, arrives with two default habits: to take a daily walk, and ring a friend.

At the bottom appear "guided journeys", or sample practices you can select to exercise in the habit app gym. For example, becoming a more committed opponent of racism is one, doing 100 press-ups a day is another.

Or, you can choose your own. I add "Run for an hour", and "Colour two boxes" on the days I selected. It is strangely satisfying.

Short-term rewards like this are important for changing our habits, says Prof Kelly. Doing physical exercise just to be healthier "is not enough to sustain a daily habit", he warns.

And to get a new habit or change an old one, the change "needs to be small, should ideally be tied to an existing habit, and must be rewarding in the short term," Prof Kelly adds.

Changing habitual behaviour is the 'hardest thing', says Jake Bernstein

So, apps can help contribute toward short-term rewards. And also tie our new habits to existing ones. Like checking our mobiles, or sharing things we've done with our friends.

Telling people in our lives about our attempts to change a habit can also make us work harder - because we then have friends to hold us accountable.

"We did a correlation analysis. How many friends you had on the app was correlated with how successful you were in changing your habits," says Jake Bernstein, SnapHabit's co-founder.

Similarly, Habitica, another app, includes "a quest function that incorporates social accountability," says Vicky Hsu, who was an early user of the app and then became chief executive of the company behind it.

"If you don't do any of the things that you've committed to for the day, then the app takes away points from you and from everyone else who's opted in to participating in the quest with you," explains Ms Hsu.

And collecting "random pets" as part of the game helped her stay on top of meditating, exercising, and going to bed on time, she says.

"I found the visual representation of the work I was doing extremely helpful, especially since I do a lot of intangible work that doesn't necessarily feel productive," says Ms Hsu, who also practises as a lawyer.

On SnapHabit, the largest group, 32.7% of users, is trying to exercise more. In second place, 15.9% are trying to build habits to learn or study.

Mr Bernstein says he was surprised by some of the habits people set up - for example, "not masturbating".

Getting an exercise habit is the most popular function on SnapHabit

If an app successfully helps us change our habits, it's likely because it mirrors behavioural principles for how we can best train the basal ganglia in the striatum in our brain.

One aspect is cognitive load: this is the mental effort involved in completing a task or learning new information.

We're more likely to learn a new habit when this is low, so by marking tasks we've completed, an app can reduce it, and make forming the habit easier for us.

Another is called the "Zeigarnik effect": we remember incomplete tasks more than ones we've completed, external.

So, by showing progress bars or percentages, an app can help remind us of our tasks in progress.

Talking about the origin of his own app, "I originally built it to solve my own problem," says Mr Bernstein.

"I know the things that I enjoy doing and that give me fulfilment, so how can I map the way I spend my time to those things."

He had begun quantifying his time with a Fitbit, but when Covid started he wanted to make it "more social, make us more connected and help us meet our goals together".

Be careful when developing new habits, advises Dr Shubhangi Karmakar

It's a similar story to Kyle Richey's, founder of the Strides habit app. "In 2011, I was using to-do list and calendar apps to manage my day," he says.

These were "awesome replacements for their analogue counterparts, but I felt like something was missing," he observes.

"I wanted to do more than put an "!" on a task. I needed a way to prioritise the right things and use behavioural science techniques to stay motivated and focused."

Apps that show you the number of consecutive days you've followed a new habit represent "a super powerful tactic but can also be incredibly frustrating if you drop them", says Mr Bernstein.

It's important "to be compassionate to yourself when you fail," he says. And take away something positive, like insight about what motivates you.

An app "will never tell you to take a break and look after yourself," says Shubhangi Karmakar, a junior doctor in Dublin and an editor of the British Journal of Psychiatry. "The important thing isn't just to form a habit, but to form a healthy one," she says.

Changing our behaviour is "the hardest thing", adds Mr Bernstein. And ultimately, apps like these on their own can only go so far.

After all, for me, the consecutive number of days spent working on my doctorate still remains stubbornly stuck at zero.