Would you give 10% of your salary to charity?

- Published

John Yan says he wanted to help people less fortunate than himself

John Yan has decided to start giving away at least 15% of his annual salary, despite it meaning that he'll have to work longer into his old age.

The 27-year-old software engineer began donating part of his wages in 2019, pledging 1% that year, before raising it to 3% in 2020, and then a big jump to 15% in 2021.

"In practical terms this commitment means I'm not going to retire early," says Mr Yan, who lives and works in New York City. "And maybe looking ahead, I won't be able to send my kids to private [fee-paying] school."

He is donating the money via a global scheme called Giving What We Can (GWWC). This encourages people to sign up as a member and pledge to give 10% of their earnings to charity.

Members can either donate directly to a charity of their choosing, or pick from a list that GWWC recommends. The later includes some funds run by the initiative's parent charity - Centre For Effective Altruism - which is registered in both the UK and the US.

Mr Yan, who is the child of first-generation immigrants to the US, says he knows that he is "doing better than a lot of people in the world" and wanted to give something back - to help others.

"I realised it could only cost a small amount of my happiness to give a greater amount to other people," he says.

Could you afford to give 10% of your salary to charity?

GWWC was founded in 2009 by two Oxford university students - Will MacAskill and Toby Ord. Both are now philosophy academics who focus on "effective altruism", which explores the most effective ways to help others.

It is claimed that 6,439 people around the world have now signed up, with more than $244m (£183m) donated so far. Members record their donations on the scheme's website. And while the pledge is designed to be a lifetime one, people can drop out if their circumstances change.

Far from the pandemic slowing down the number of people signing up, GWWC says that it saw its fastest-ever growth in 2020.

More than 1,000 new members signed up last year, as Covid and lockdowns made many of us think more about others and a bigger world picture.

A further 1,000 people are said to have made one off donations via GWWC in 2020, or agreed to give less than 10% over a more limited timeframe.

But why encourage people to give away 10% of their income rather a than higher or lower level?

"The amount was chosen because it strikes a good balance of being both significant and sustainable," says GWWC executive director Luke Freeman. "It is a significant proportion of one's income, but it is also within reach of most people in rich countries."

He also points to the historical connection of the idea of tithing, a tradition in both Judaism and Christianity of giving 10% of your income to charity or the church.

The 10% pledge is a minimum, and some members, such as Mr Yan, decide to give a higher amount.

Will MacAskill has given Ted Talks on effective altruism

Pippa Gilbert started donating 10% of her income to GWWC a few years ago.

"I had much more than I needed to live on, and much of the world doesn't, so it seemed obvious to me," says the 60-year-old who is from The Hague, Netherlands.

This year Ms Gilbert retired from her job as analyst for an international organisation meaning her income has fallen. "But it's still more than I need personally," she says.

While those signing up include students, retirees, trades people and investment bankers, Mr Freeman says that there is a skew towards people on middle to higher incomes and those with higher education levels - the median age of members is about 30.

"While many on lower incomes find great meaning in their giving, we do particularly encourage those who have more to give more," says Mr Freeman.

Pippa Gilbert, who is newly retired, says she has more than enough money to enable her to spare 10%

Boston-based couple Julia Wise and Jeff Kaufman are two high earners who are now donating 50% of the combined salary to charities - mainly, Against Malaria Fund and Malaria Consortium.

They do this via a non-profit organisation called Givewell, which researches charities to establish which ones are the most effective.

"I felt from an early age that we should be sharing in some way to make the world a better and fairer place," says Ms Wise, 36.

New Economy is a new series exploring how businesses, trade, economies and working life are changing fast.

However, GWWC, and the wider effective altruism movement, are not without their critics.

These say that such charitable donations should never be seen as a substitute to a decent level of taxation and state social services.

Julia Wise and Jeff Kaufman give away half of their combined income

"It's great that people are giving more money to charity, but this cannot be a substitute for an adequate social security safety net funded by higher taxes," says economist Jeevun Sandher from King's College London.

"US citizens consistently give more to charity than those of any other nation (a record $471bn in 2020, external) yet the US also has the second-highest poverty rate in the OECD - the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, external - this is not a coincidence."

"There are three reasons why charitable giving cannot be a substitute for a well-funded welfare state. Firstly, the amounts given in charitable donations simply do not make up for a well-funded welfare state.

"Secondly, giving low-income people cash is the most reliable way to help pull them out of poverty. Charities that provide food, classes and youth centres for those on low-incomes do improve lives, but they cannot replace cold, hard cash.

Finally, charitable giving is not a reliable source of income, nor is it available to everyone on low-incomes."

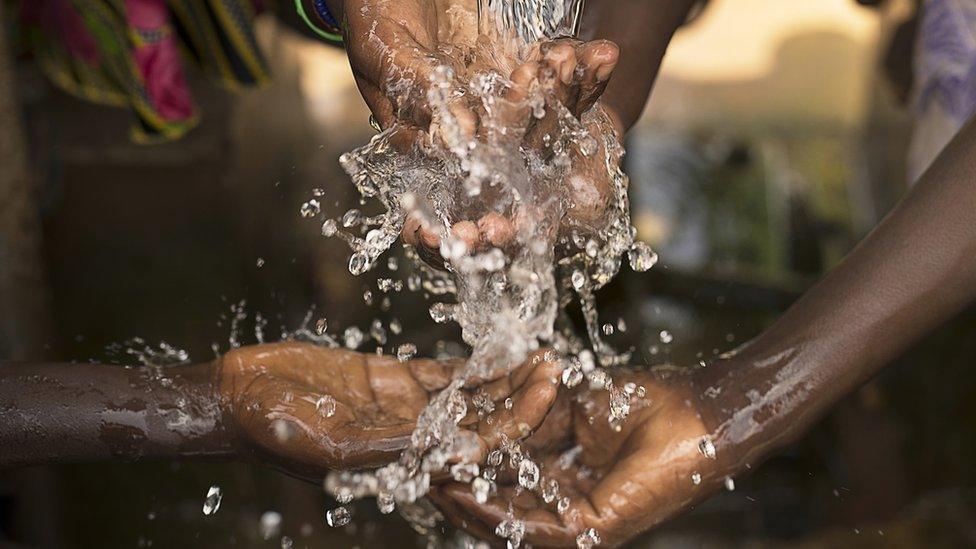

GWWC recommends charities, but people signed up can give to whoever they want

Jennifer Rubenstein, assistant professor of politics at the University of Virginia, and author of Between Samaritans and States, adds that effective altruism "does not empower poor people as political actors or entities".

Mr Freeman counters that charities still play a vital role in helping to tackle extreme poverty around the world.

"Many of us are wealthier than we think, and many of us can make effective giving a meaningful part of our lives," he says. "A median income in countries like the UK puts you comfortably within the top 5% richest people in the world.

"That money can improve the life of someone in extreme poverty by about 100 times more than it can improve your own life."

Additional reporting by New Economy series editor Will Smale.