The shipping giant banking on a greener fuel

- Published

Maersk's new green-fuel ships will be about the size of this container ship

Right now, there are around 50,000 merchant vessels out at sea, or docked at a quay somewhere.

Ordinarily, their work keeps the entire global economy moving but it's been a very turbulent few days for the shipping market. The Russian invasion of Ukraine is causing major disruptions for the industry, with many vessels stuck in ports and freight costs rocketing higher.

In the wake of sanctions, shipping giant, Maersk has temporarily suspended its container shipping to and from Russia (except for food, medical and humanitarian supplies).

These vessels criss-crossing multiple trade routes around the the globe generate a staggering 3% of the world's carbon dioxide emissions - about the same volume as Germany.

The European Union is working hard to cut those CO2 emissions with several schemes designed to make using fossil fuels more expensive, external.

But the problem for shipping firms is that alternative, or 'greener' fuels are still only produced in tiny quantities compared with traditional marine fuel.

Nevertheless, Maersk, has made the decision to order 12 ocean-going ships which run on methanol. Each costs $175m (£130m) and is capable of carrying 16,000 containers.

Jacob Sterling, Maersk's head of decarbonisation innovation and business development. hopes those vessels will kick-start the market for shipping powered by methanol, which is potentially a greener source of fuel for the industry.

"We have had this chicken and egg dilemma," says Mr Sterling. "We think this will unlock the scaling that needs to happen."

Jacob Sterling from Maersk hopes their order for ships will kickstart demand for methanol

Maersk acknowledges it will be challenging to source enough green methanol to keep the ships running.

"We believe there's only 30,000 tonnes of fuel being being produced now in the world [every year]," says Mr Sterling.

It's likely at least 15 times that will be needed to fuel Maersk's new ships alone.

With a fleet of almost 700 vessels, Maersk is one of the biggest players in shipping. "We emit a lot of CO2. We need to do something about it," says Mr Sterling.

As part of this strategy, a smaller container vessel, the first of its kind, will be launched on the Baltic Sea next year.

Maersk estimates these new smaller ships could save 1.5 million tonnes of CO2 per year, or 4.5% of its fleet's emission.

This may seem a drop in the ocean but Mr Sterling adds, "This is exactly why we need to get started now."

The new vessels are designed to also operate on dirtier marine fuel, however that is only a back-up and the plan is to run them on green methanol from the outset.

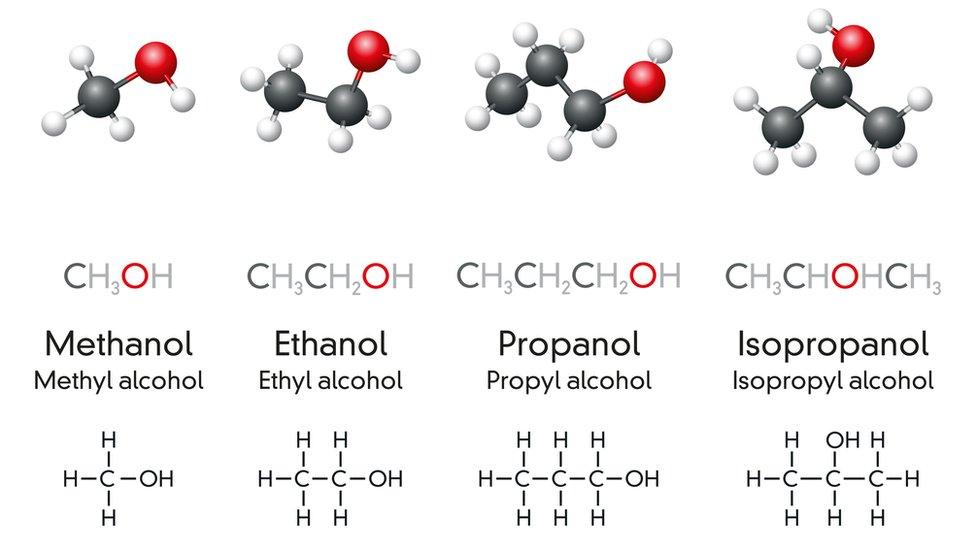

Methanol is the simplest member of the alcohol family

Methanol is part of the alcohol family of chemicals used in paints, plastics, clothing fabrics and pharmaceuticals, and as a vehicle fuel.

Unlike hydrogen, which is also promoted as a green fuel, methanol does not need to be stored under pressure, or extreme cold, and many ports already have the infrastructure to handle it.

"We think this is the good solution to get started with," says Mr Sterling. "It's relatively easy to handle on ships, and the ship technology is well known."

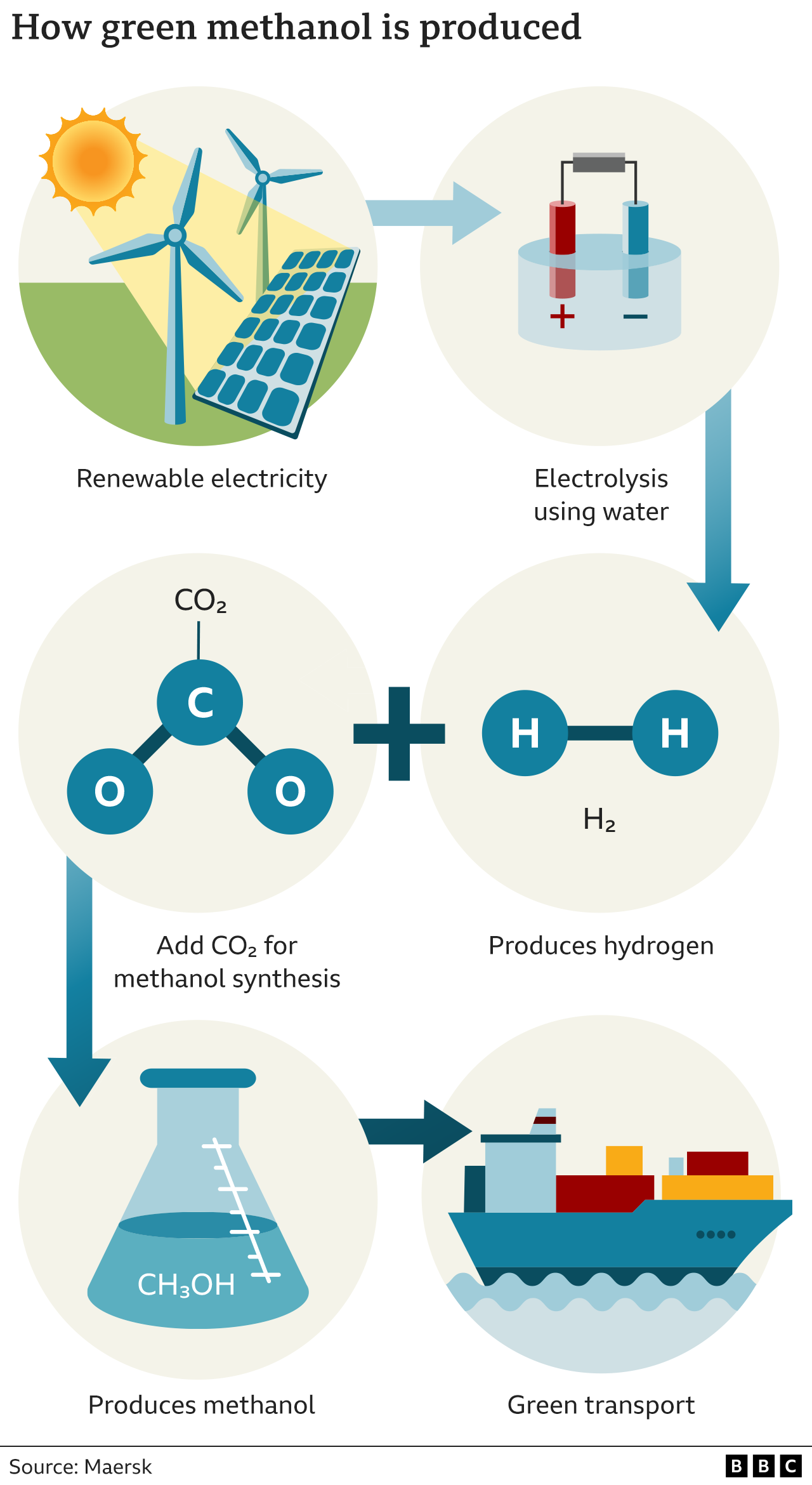

At the moment most methanol is derived from natural gas. Green methanol does not rely on fossil fuels and can be made in a couple of ways.

Bio-methanol is produced from biomass, such as agricultural waste. Heat, steam, and oxygen are used to convert the biomass into useful fuels, including methanol.

There's also e-methanol. Here renewable electricity splits water into oxygen and hydrogen, which is combined with carbon dioxide.

"Methanol is a hydrocarbon fuel. Burning it generates emissions out of the ship's smokestack," says Xiaoli Mao, from the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT).

But, in its favour, green methanol has a low carbon footprint, if you look at the whole production process.

That is because the methanol has been derived from CO2 from the air, or CO2 that has been captured by plants, which roughly cancels out the CO2 released when the methanol is burned as fuel.

"You have to have a sustainable source of carbon," explains Ms Mao.

However, she points out that both technologies for capturing CO2 are "very nascent and very expensive".

Accurately measuring emissions during the lifecycle is also complex. "[It] requires a lot of measurement and certification throughout the production and supply chain," says Dr Tristan Smith, a low-carbon shipping expert from University College London (UCL).

"In practice, the production process even of biomass derived-methanol is energy intensive and normally has a carbon footprint," he says.

Danish firm, European Energy, is among the very few green methanol producers. It's set to supply 10,000 tonnes of e-methanol for Maersk's first vessel. Although later this year, construction of a commercial-scale plant near Aabenraa in southern Denmark will start. Operations begin in 2023.

Once fully ramped up it is hoped the site will produce at least 30,000 tonnes of methanol a year.

The plant will harness solar power and carbon dioxide from biogas production, which uses manure.

Soeren Kaer says the carbon footprint of methanol is 'very low'

"We take in CO2 that is captured by the plants or the crops from the atmosphere," says Soeren Kaer, Head of Technology, at the firm's Power to X division.

"The plants used as animal feed, have a very short rotation cycle. So, it's really a circular process. In terms of the greenhouse gas impact, it's very low," explains Mr Kaer.

Scaling-up is one of the biggest challenges for green methanol production, "but that would be the same for any new fuel," he says.

Compared to conventional marine fuel, green methanol is twice as costly and the new vessels are 10-15% more expensive to build.

However, even if that means higher costs passed on to customers, Maersk's Jacob Sterling says clients are on board. "We do see customers that are willing to pay a premium for carbon neutral transportation."

The company has the deep pockets needed for investment, and has recently seen profits soar.

Maersk has also invested in other start-ups developing sustainable alternative fuels.

Dr Smith says the shift to green methanol is a welcome step. "These ships have the potential to achieve much lower greenhouse gas emissions than ships being operated today."

However, he thinks another fuel, ammonia is a better long-term solution. But this technology is also still being developed.

"I think that the end game for shipping is not going to be one fuel," says Mr Sterling. "It will likely be a patchwork of technologies and fuel types."

"We go for methanol now because we can, and because we think it's a good solution. But we'll continue to innovate."