What does egg freezing have to do with your employer?

- Published

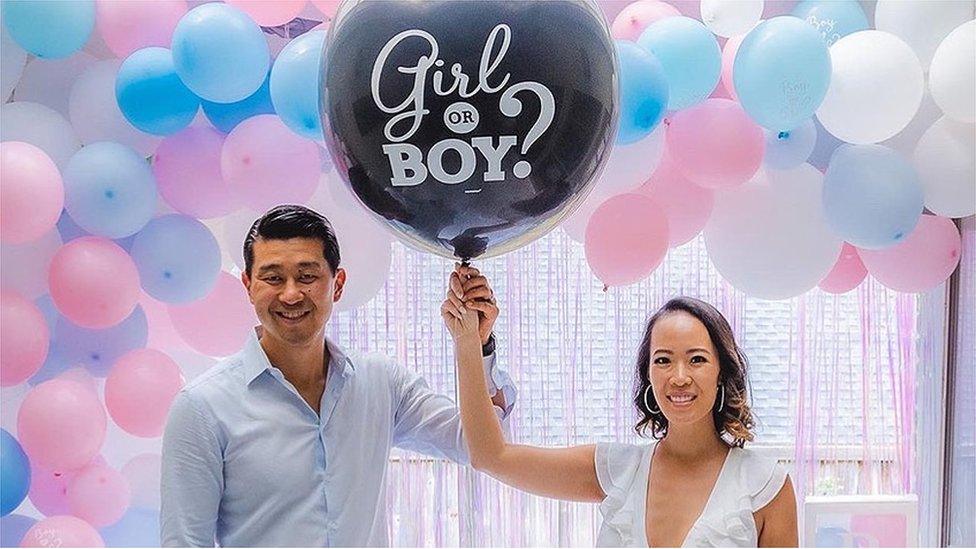

Carol Chen and her partner at a gender reveal party

Born and raised in Texas, successful entrepreneur Carol Chen has built a life and several fashion businesses in Singapore.

She always dreamt of becoming a mum. But there was a snag. Having her designs showcased at Paris Fashion Week - no problem. Finding a life partner - much more difficult.

When she hit her mid-thirties, she started to worry.

"I just started reading a bunch of material online that says your body really becomes much less fertile after 35. I started freaking out," she says.

She was single, so decided the time was right to freeze her eggs - a method of preserving fertility, so she could potentially try and have children at a later date.

It's a relatively new process and success rates vary significantly, depending on how many eggs the woman freezes and her age at the time.

A 2016 study of 1,171 in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) cycles using frozen eggs, found for women who froze five eggs at age 35 or younger, the chance of a live birth was 15%. While this chance increased to 61% for women who froze 10 eggs and 85% for women who froze 15 or more eggs.

Eggs and embryos can be gathered and frozen in deep freezes using liquid nitrogen

While, a more recent study, external found 70% of women who froze eggs when they were under 38, and thawed at least 20 eggs at a later date, had a baby.

When weighing up this data it is worth bearing in mind that the birth rate for IVF itself is low; just 24% per embryo transferred, according to the UK's Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority.

In spite of these odds, egg freezing may be growing in popularity, For example, in the US in 2017, 10,936 women froze their eggs - or 23 times as many did in 2009,but that already feels like old numbers.

Singapore is the latest country to lift the ban on egg freezing for non-medical reasons - this will kick-in from January 2023.

In the UK, egg freezing is not normally covered by the NHS, unless you have a medical condition impacting your fertility, for example, certain cancers or lupus. Although the UK Government recently announced a 10-year limit on storing frozen eggs, sperm and embryos will be scrapped.

A significant investment

There's no question the procedure is quite a financial undertaking. Carol spent almost $14,000 (£11,400) for one round of egg freezing and had to travel the US to do it. She didn't have as many eggs as she wanted, which she says made her feel "less of a woman."

She is overjoyed for Singaporean women and hopes many more Asian countries will follow.

"Even in the US, as an Asian-American, it can be a taboo as a second-generation immigrant," she says, although adding she feels plummeting fertility rates may force the authorities' hands in some countries.

In the end, Carol was lucky. She never needed to worry about paying for another round of egg freezing. Two years ago, she met her now husband and managed to conceive naturally in her 40s.

In fact, the percentage of women who actually use their frozen eggs remains very low, below 10%, external .

Another mini study , externalanalysed data from London's two largest fertility clinics; over this ten-year period, 2008-2017, only about a fifth of patients who had frozen their eggs at the clinic - returned to use them.

But that trend has not some stopped employers including it in an ever-expanding portfolio of fertility benefits.

The trend started, unsurprisingly, in Silicon Valley in 2014, when Facebook and Apple began offering egg freezing to their employees as part of their benefits package.

Fast forward eight years and big corporate firms are really struggling to recruit and retain workers, so various fertility benefits have gone from novelty to a must-have. Just under 40% of large companies in the US, so those over 500 employees, offer them.

Even in Europe, with its much more generous, state-funded health services, some firms are starting to follow suit, Social media marketing firm, Hootsuite, for example.

In the UK, companies like banking group, NatWest and energy firm, Centrica, offer up to £45 000 per employee for an appropriate treatment or service.

Jenny Saft, is co-founder of a tech platform providing fertility benefits, working with employers across Europe. She says the picture is complex and there are many limitations and restrictions in accessing state-funded fertility treatments - so companies are increasingly stepping-in.

In Germany, for example, health insurance covers half the costs for up to three IVF cycles, but only if you're married, in a heterosexual relationship and aged under 40 if you're a woman, she says.

Dr Lucy Van De Wiel is concerned employees using corporate fertility benefits may feel under pressure to 'time' having kids

But not everyone thinks directly involving a company, or boss, in your fertility is good news.

Dr Lucy Van De Wiel is a lecturer in Global Health and Social Medicine at King's College London. She calls these employment policies a "PR technology", that is successful at "attracting and retaining female staff, and that is how it is sold by the insurance companies to employers."

Dr Van De Wiel is worried that the insurer gains a central role in how people approach their reproductive choices, which could lead to excessive commercialisation of fertility.

She recognises that, on one hand, it's great that women get more information about their fertility, but her worry is that, this education could be coming from companies that stand to gain financially from people using those technologies. "It's very hard to avoid any kind of conflict of interest."

This is a particular concern when it comes to egg freezing because, versus IVF, almost all women below a certain age could be treated as a potential client. Every woman who may want to have a child in the future could be a candidate for egg freezing.

Dr Van De Wiel says there are studies showing women who are offered these services are quite happy to have options but also feel their employer may be telling them that they have to 'time' having children.

Nyasha Foy feels egg freezing gives her not just 'body autonomy' but 'life autonomy'

New York-based entertainment lawyer, Nyasha Foy, is aware of the potential conflict of interest here.

Her firm offered to pay for two rounds of egg freezing and storage, and she took up the benefit.

"I absolutely do see this idea that if I give you $10,000 for the egg freezing, the return on the investment of you working one or two more years in this company, is a win," she says. "There's a sense of that kind of energy and you feel a little funny about it, right?"

However, Ms Foy thinks women can change the dynamic and do it for themselves.

"I didn't meet my man in college, didn't meet my man in law school," she explains, "so there is this sense in the back of your head that you need to hurry up and just have a kid. I'm OK with the commodification of it, especially in America, as we're having to revisit Roe v Wade. To be able to say as a woman, I choose to just wait a little bit longer. That choice is not only body autonomy, that is life autonomy," she concludes.

Fertility doctor, Aimee Eyvazzadeh, AKA the 'egg whisperer' is known for throwing egg freezing parties

There is no denying that egg freezing is only gaining momentum in the developed world, and fertility clinics are fighting to attract customers by any means allowed.

Fertility doctor, Aimee Eyvazzadeh, AKA the "egg whisperer", is based in California, and is known for throwing egg freezing parties in "swanky restaurants with beautiful bars and lovely food."

She concedes it is a worry that freezing is talked about as a way of "taking control", or as an insurance policy. "You might have given yourself a future chance, but the chance may not have been as great as you had once thought," she adds.

Dr Eyvazzadeh's average patient is 39 years old. She thinks that in 15 years that could rise to 49. Therefore, she believes young women, who have no fertility issues, should strongly consider freezing their eggs - "for their 40-year-old selves."

Meanwhile, on the other side of the US, Nyasha Foy is considering her next steps. She hasn't yet used her frozen eggs and is still hoping to meet her "baby daddy" first,

"I'm 37 now. If I get to a place where I can't carry a baby, I am in a position where I could potentially get a surrogate," she says.

"I want to be a mother. I know that I'm going to get there. I don't know how or when, but I've done what I can do to give myself the best chance."

Related topics

- Published29 June 2022

- Published26 June 2022

- Published18 June 2022

- Published25 February 2022

- Published2 February 2022