Cost of living: 'No-one likes us. We DO care. We are Millwall'

- Published

Christine Cunningham has been helped by the club

A chant delivered for decades on the terraces of Millwall football club goes: "No-one likes, no-one likes us, no-one likes us. We don't care."

But Christine Cunningham knows that is not true. The club and its fans do care - especially now when the soaring cost of living is making life so hard for those who live in the neighbourhood.

The 58-year-old benefits from the on-site food bank which is stocked in part by donations brought by supporters on match days.

"It is the difference between having something hot on a bit of bread, or nothing," says Mrs Cunningham, a grandmother of 11.

"I felt a bit too proud to come at first but, blimey, those food prices are high and there is only so much you can cut back on."

Kelly Webster runs the food hub at The Den

The Lions Food Hub is inside Millwall's stadium - The Den - in Bermondsey, south east London. It is run by Kelly Webster, a former player for Millwall's women's team - the Lionesses - who herself has struggled for money in the past.

"I've been homeless, in a hostel eating sweetcorn and hotdogs. Now, I felt I had to give something back," the 46-year-old says.

Having hung up her boots, she provides food for about 50 local families at the hub, serving people aged anywhere between their early 20s and mid-70s.

Milk, food, butter, sausages, mince and a range of canned food all come in, or are bought from cash donations, then go out to those in need.

It seems an unlikely location for a food bank, but reflects a wider campaign among English Football League (EFL) clubs to support their local communities.

'Family' support

The fact that it is Millwall who is at the vanguard of this campaign is significant. For many years, the club has suffered from a poor reputation, in part caused by the behaviour of some of its fans, hence the "no-one likes us" chant.

Steve Kavanagh, the club's chief executive, says that the notoriety means they have to work harder to help out a primarily working-class fan base and local community.

"You soon realise this is a family club, and we can see what people are facing at the moment," he says. "Like all families, it can be dysfunctional and difficult, but we look after each other. We feel we have to go even further because of our history."

To emphasise his point, he is speaking in the club's boardroom which is full, not of wealthy football club bosses, but of locals enjoying a free coffee morning.

The weekly session began when Covid lockdowns were lifted, giving older fans the chance to come somewhere safe and to encourage them to get back out into society. Now, it has a financial element too, and is a warm place for people to meet.

Peter and Kenneth Saville attend the coffee morning at Millwall

Among them is 88-year-old Kenneth Saville, who says he comes to the coffee morning for "family, company and cake".

His son and carer, Peter, says: "Everyone is welcome here. It doesn't matter if you are a [Millwall] supporter, or not."

There are people across the country just like Kenneth, Peter and Christine - all affected in different ways by the soaring cost of living - who are getting some support from their local club.

Some are offering cheaper, or free, tickets but - as Mr Kavanagh points out - that is not always appropriate for someone who cannot afford the petrol or fare to get to a match in the first place.

So instead, much of the support is practical, ranging from a cafe at Cambridge United and free wi-fi at Middlesbrough, to debt advice at Rochdale and a warm room at Rotherham United.

Trevor Birch, chief executive of the EFL, says it means "real tangible help" for those people hit hardest by the cost of living.

"While EFL clubs support people all year round, we recognise that now more than ever we should come together and maximise the power of our network to support people who are struggling," he says.

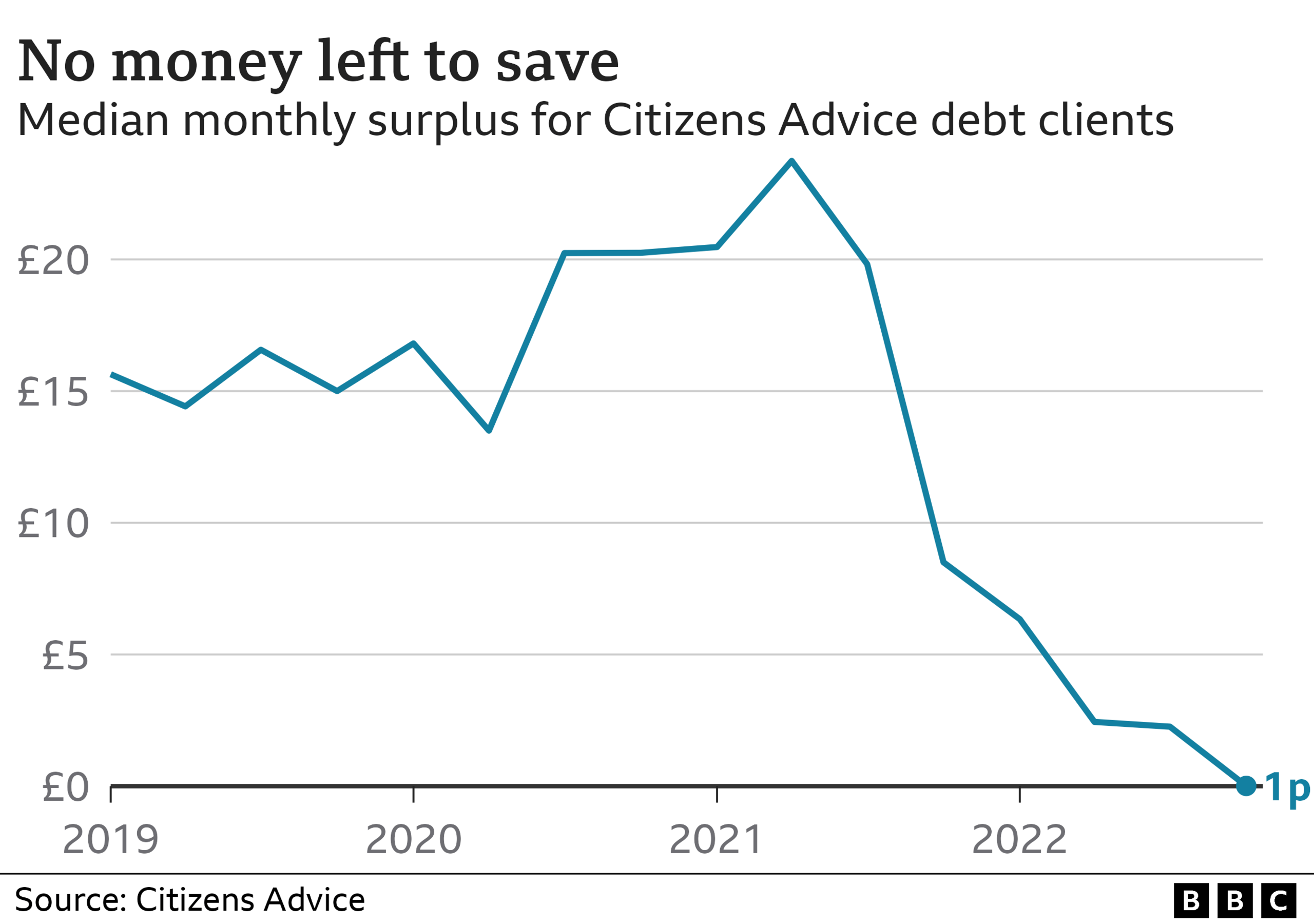

Data provided to BBC News by debt charity Citizens Advice shows why such support is often necessary.

It carries out debt assessments for people seeking help. While people typically owe less money than equivalent clients in the past, an increasing proportion are in the red after covering their basic outgoings, known as a negative budget.

As a whole, those going through debt assessments typically have 1p left at the end of the month after essential spending - such as food, heating and rent - reflecting the impact of rising prices and bills.

This is why so many people, possibly football supporters themselves, need extra support - some of which is being provided by their local club.

Guide to dealing with debts

Work out how much you owe, who to, and how much you need to pay each month

Identify your most urgent debts. Rent or mortgage, energy and council tax are called priority debts as there can be serious consequences if you do not pay them, and so they should be paid first

Calculate how much you can cover in debt repayments. Create a budget by adding up your essential living costs like food and housing, and taking these away from any income such as your wage or benefits you receive

See how you could boost your income, primarily by checking what benefits you are entitled to, and whether you are eligible for a council tax reduction or a lower tariff on your broadband or TV package

If you think you cannot pay your debts or are finding dealing with them overwhelming, seek support straightaway. You are not alone and there is help available. A trained debt adviser can talk you through the options available

Source: Citizens Advice

Related topics

- Published1 December 2022

- Published3 December 2022

- Published22 October 2022

- Published29 November 2023

- Published29 November 2022