Why hasn't mortgage pain led to a housing crash?

- Published

The black clouds are rising above the mortgage market.

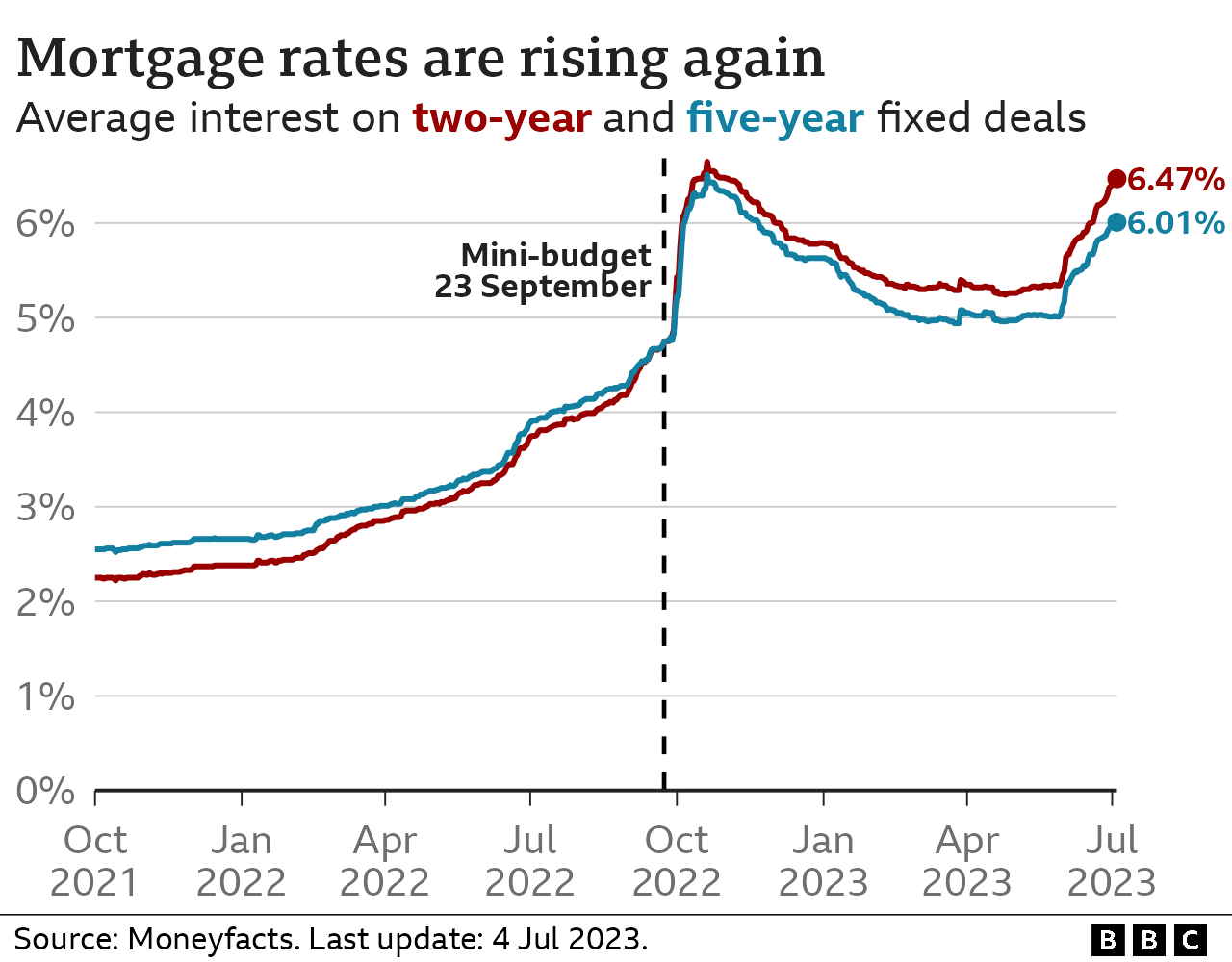

House prices are beginning to show notable annual falls. Fixed mortgage rates now mostly start with a 6%.

The City is starting to predict a prolonged peak in UK base interest rates of 6.5%, with some seeing a case for 7% rates.

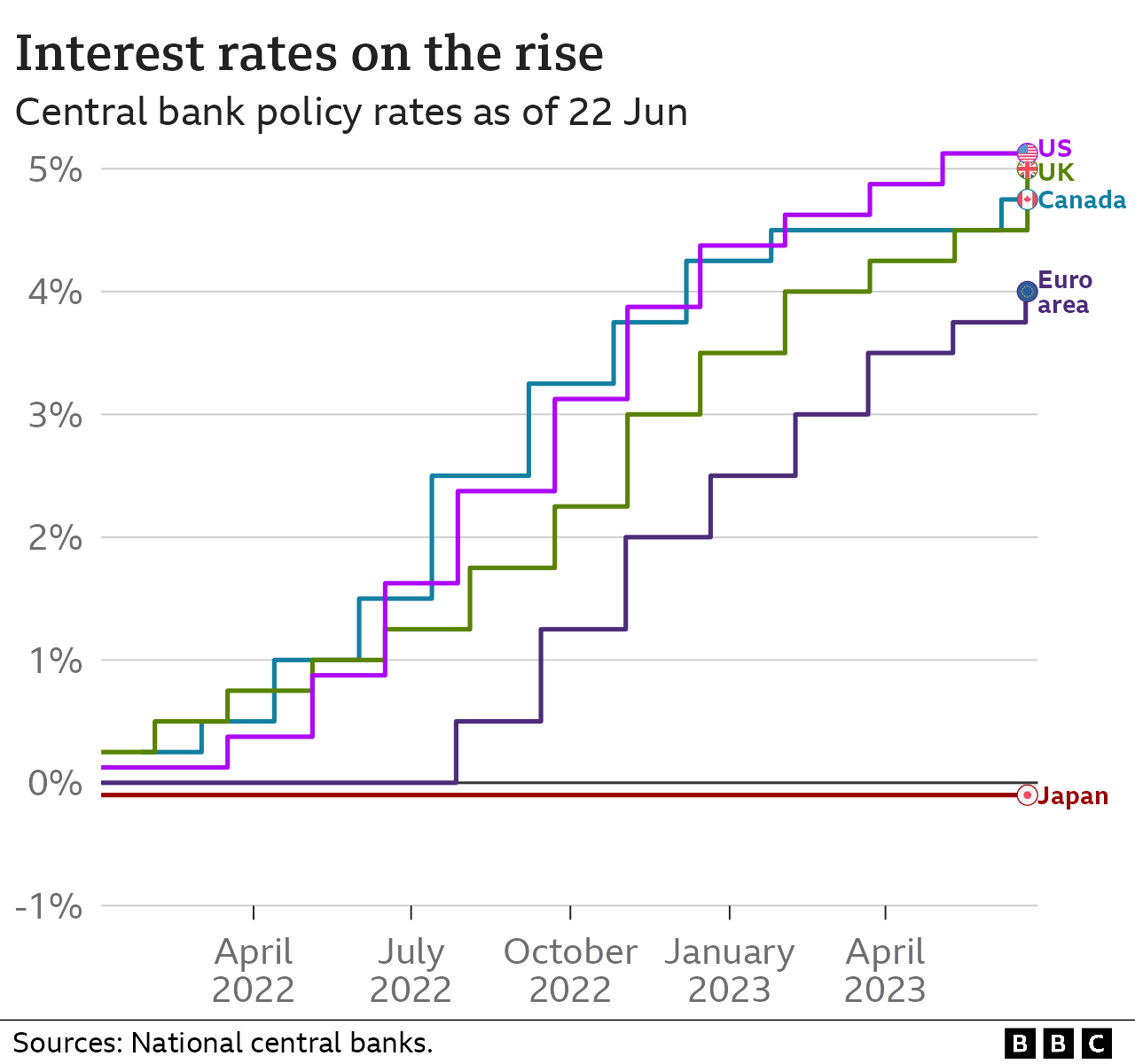

In financial markets, the UK is starting to diverge from other western economies: longer term borrowing rates for government are now at 15-year highs, above where they got to after the ill-fated Liz Truss mini budget.

While this is not a panic, it is a notable squeeze; the result of market perceptions that sticky UK inflation in particular will mean higher rates for longer in the UK.

It now costs the government two percentage points more to borrow over 10 years than the German government. That was 0.7 percentage points just three months ago.

When the government came into office 13 years ago it promised to avoid the-then fate of the Greeks in the borrowing markets.

But it is now notably cheaper for Greece (3.99%) to borrow over 10 years than Britain (4.67%).

This does not reflect solvency fears, but it is a judgement for UK authorities on whether inflation is under control.

This week the government borrowed effectively £4bn over two years from the markets at a gilt auction.

It had to pay, at 5.7%, the highest rates this century over two years, the second highest this century on any UK government bond.

Added to all of this, interest rates are higher for the government to borrow over two years than it is over 10 years.

That's unusual and often a sign of a coming recession.

In the jargon, the yield curve is "inverted". This is very consequential for banks' business models, their savings rates, and risks to their funding or liquidity.

All of this provides the backdrop for those mortgage lending rates.

The move so far from just above zero to 5% is the "biggest and fastest move any of us can remember" according to Andrew Bailey, the Governor of the Bank of England.

So really the question is, why have house prices not fallen even further? And the related point is - should that in fact be the aim, or at least a test of what the Bank of England is trying to do in getting inflation down?

Late last year Jerome Powell, the US Federal Reserve Chair, was very clear in public that a "housing correction" was an immediate sign that raising US rates was having the desired effect.

To be clear, we are not yet seeing a price correction, arrears, a spike in repossessions, or people forced to sell, that would be expected from the hike in interest rates.

To give some context, typical house prices on the Halifax measure are now £285,932.

That is down on the peak last August of £293,992, but still well up on the figure two years ago (very relevant for those remortgaging two-year fixes) of £260,358.

The pre pandemic level of house prices in December 2019 was £238,963.

Is the housing market more cushioned from rate rises? Clearly the prevalence of fixed rates makes a difference.

But two thirds of the impact of the existing rate rises will hit the economy as people roll off those fixed rates.

But even that can not explain the relatively benign impact so far.

The mortgage banks are behaving differently to how they have acted in previous aggressive rate rise cycles.

They are really trying to avoid repossessions. Their departments dealing with arrears are no longer even called "Collections and Recoveries" as they were back in the 1990s.

They are extending mortgage terms, offering payment holidays, switching appropriate customers to interest-only deals.

They are also using their customer data to identify subtle financial stresses at an early stage.

They run models of hundreds of thousands of their customers to find the key signs for what might become arrears.

Regular trips to a discount supermarket, from a former Waitrose customer, is, I'm told, a clear sign for intervention.

Using machine learning they can calculate probabilities of whether customers will face a negative budget by, say, the end of the year.

Much of this is automated, and allows early interventions and the consideration of more subtle patterns of spending across the population.

In the 1990s, actual human bank managers would be enforcing more rigid affordability guidelines.

"Literally the last thing I ever want to do is repossess someone's home," I was told by one top mortgage industry boss.

"We do an income and expenditure analysis, a budget analysis with somebody who's struggling to pay. So long as they can afford to pay a pound - I want to keep them in their home."

The candidates for repossession are those who are obstructive or do not communicate at all.

Or in cases where candidates for flexible treatment can simply no longer afford to live in their homes, and would be better served in selling up, downsizing and extracting equity.

While these numbers will inevitably grow, for now, they remain remarkably low.

Just over 400 repossessions a month occurred in the first three months of the year. In the early 1990s it was more than 5,000 a month.

There is another reason for the, so far, soft landing in the housing market.

The economy is very divided and unequal. The poorest section of society do not have mortgages.

The richest are still up from the period of lockdown-forced savings and super low interest rates.

In the middle, millions of households face a significant and painful squeeze from rising mortgage rates, but the banks' models tell them it can be afforded, albeit with significant adjustments to spending habits.

The jobs market, for now, remains resilient, even as companies' borrowing costs are also starting to spike.

To rephrase former Conservative Chancellor John Major, if it isn't hurting, is it working?

Are the Monetary Policy Committee turning the tap harder and harder on the interest rate hose to try to dampen down the inflationary fire, but finding only a slow trickle of water?

Put another way, will the Bank of England have to raise rates higher than it predicted, to temper demand and spending power in the economy?

Allan Monks, the UK economist at JP Morgan, calculates that had every mortgage been variable, then the affordability shock to the economy would already be the same as the 1980s.

He can see scenarios where interest rates might have to go as high as 7% to rein in inflation.

Conversely the former Bank of England chief economist, Andy Haldane, fears what he called "monetary austerity", calling for some calm in financial markets and on the Monetary Policy Committee.

Even before new inflation figures that might show inflation still above 8%, there are some important milestones this week.

On Tuesday mortgage lenders are up in front of MPs.

On Wednesday, the Bank of England releases its biannual assessment of financial stability of the banking system and households.

And on Monday we hear from the Chancellor Jeremy Hunt and the Bank of England governor at Mansion House.

Financial markets are flashing a warning signal. The housing market has so far been intriguingly immune.

That might not be good news.

Related topics

- Published4 July 2023