Why can’t the world keep its promises?

- Published

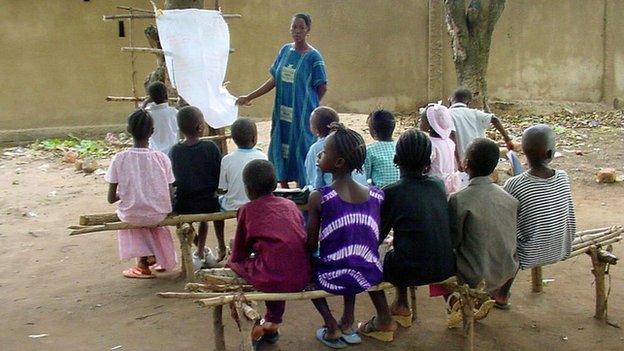

Open-air classroom in Guinea in 2001: Even such basic education is still unavailable to millions

In April 2000, in a wave of new millennium optimism, world leaders promised to deliver something at the beginning of the 21st Century that in many developed countries had been taken for granted by the end of the 19th Century:

Primary education for all children.

This basic gap was going to be fixed within 15 years, so that by April 2015, the unacceptable position of millions of children never even beginning school would be consigned to history.

This was one of six Education for All pledges, which included targets such as girls having equal access to learning, and a halving of adult illiteracy.

Kofi Annan, UN secretary-general at the time, said that getting this completed by 2015 would be the "test of all of us who call ourselves the international community".

Well, here were are in their future.

How many of the pledges were fulfilled? None of them.

Initial optimism

Unesco's Global Monitoring Report, which painstakingly tracked the progress, saw an initial surge of improvement.

But the optimism of the window that opened at the end of the Cold War gave way to the anxiety of 9/11 and then the austerity of the financial crash.

The final evaluation shows substantial progress, particularly in parts of Asia, but there are still 58 million children missing primary school, 100 million who do not complete primary school and 250 million who have schools of such poor quality that they leave unable to read a single sentence.

The obstacles that have confounded countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, have been lack of funding, lack of political will, a willingness to tolerate extreme poverty alongside extreme wealth, a rising population and the relentless destabilisation of conflict and war.

The six Education for All targets were:

Expand early childhood care and education Achieved by 47% of countries, two thirds more children in early-years education compared with 1999

Universal primary education Achieved by 52% of countries

Equal access to learning There is universal enrolment in lower secondary school in 46% of countries. But in low-income countries, one in three youngsters will not complete lower secondary school.

Adult illiteracy cut by 50% Only one in four countries achieved this goal. In sub-Saharan Africa, half of women remain illiterate.

Gender parity In 69% of countries there is gender parity in access to primary school; at secondary level, 48% of countries.

Improve the quality of education The pupil-teacher ratio has improved in more than three in four countries. But to achieve universal primary education would require an extra four million teachers.

On a more practical level, it's hard to run a school system without a reliable way of training and paying teachers, and when schools lack basic services such as electricity and sanitation.

The lack of access to education is not evenly spread. Poor girls, rural families and children from groups who are discriminated against, all end up more likely to miss out on school.

A lack of fairness within countries has been a barrier, as well as the differences between high and low-income countries.

All the evidence shows that for individuals, as for entire countries, the quality of education is often the key factor deciding the places in the global economic food chain.

And millions of youngsters never get a chance to get off the bottom.

What's possible

There is going to be another milestone world gathering next month to decide another set of targets for 2030.

And the choice of location in South Korea is a signpost to how much a country can improve its education system in a short space of time.

It shows what can be possible. And it's perhaps worth thinking about what else has arrived since the education pledges were made in April 2000.

YouTube, the iPhone, Facebook, hybrid cars, 3D printing, Twitter, the Mars rover, Wikipedia, China's and India's space programmes, mobile broadband, Skype and mapping the human genome.

Unlike building primary schools, somehow these all proved possible.