Inspiring school on the wrong side of the tracks

- Published

Pupils are very enthusiastic about their new school

Where children grow up has a far greater impact on their education than it did 30 years ago, according to analysis by the centrist think tank the Social Market Foundation.

It examined a wide set of results, including verbal reasoning tests, done by 11-year-olds enrolled in two major studies.

For both sets of children, the parents' socio-economic background was the most significant factor.

For those born in 1970, according to the authors, it didn't really matter where in England they were born and grew up - but for those born in 2000, regional difference had become "a more powerful predictive factor".

In 1970, being from an ethnic minority was a disadvantage: today the picture is more mixed, with some minority groups, like Chinese or Indian children, doing better than average.

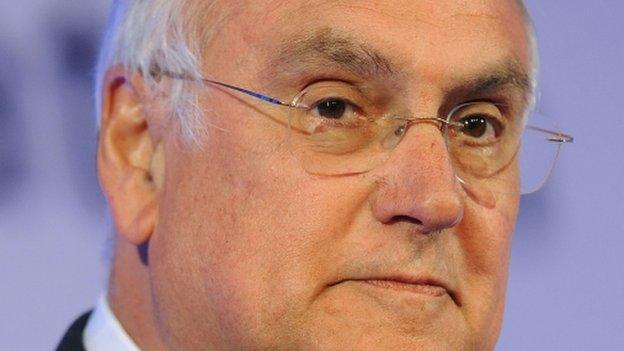

Ofsted has warned of the regional variation for several years: in 2013 chief inspector Sir Michael Wilshaw described it as "unacceptable"., external

There is considerable difference between regions at GCSE. Last year, 72% of pupils in London achieved grades of A* to C, compared to 65% in Yorkshire and Humberside.

Identifying causes

Identifying the cause of the variation is difficult. London schools benefited from the so-called "London Challenge", external, put in place by the Labour government, which encouraged schools to work together and improve practice.

Sir Michael Wilshaw has cited Hull's Boulevard Academy as a model for others

However, funding for that was cut in 2010, and the improvement in grades has continued.

"Teach First", external - the scheme which puts graduates from leading universities into schools - also initially helped schools in London and the major cities, but it has been moving into other areas.

The influx of immigrants to London and other centres is also a factor. Many immigrant parents will push their children to succeed in education - it is part of the reason why they moved.

In some of the old industrial or coastal areas, it can be difficult to overcome decades of entrenched underachievement.

In West Hull a new school - the Boulevard Academy - is trying to do just that.

It is located in an area where almost half the adult population have no formal qualifications at all: half are unemployed - half of all housing is overcrowded.

School principal Andy Grace aims to provide pupils with the right environment

The principal, Andy Grace, says parents want a good education for their children: they just don't know how to support it.

His school was classed as Outstanding by Ofsted, external last summer and cited by Sir Michael Wilshaw as a model in his last annual report - even though no pupil has yet sat a single GCSE exam.

Most pupils arrive, aged 11, with a reading level several years below their age. There are small classes. A special curriculum develops their literacy skills.

There is an extended school day, shorter summer holiday and Saturday school. Most importantly, according to Mr Grace, is the relationship he builds with parents.

Boulevard Academy:

Students are expected to arrive at the Academy at 0820 and formal learning concludes at 1630

Students are expected to attend the Academy on Saturday mornings

The summer term is two weeks longer than standard

Consequently students receive more than 300 hours extra learning time a year or the equivalent of an extra half term

Over five years, this is equivalent to almost an additional full academic year

Before a pupil starts, he will have met each family nine times: emphasising the importance of school rules, attendance and punctuality.

Homework isn't part of that: it is done at school. That is because - according to the principal - most families can't provide the right environment.

Children can't guarantee that they will be able to make themselves something to eat when they come home, find somewhere quiet, go on the internet or receive help from their parents.

The children I spoke to were positive about the school and the parents were passionate about it, saying it had given their children confidence and a love of learning.

None of them had succeeded at school and felt the teachers had written them off.

Gerry, who has one daughter at the school, and whose son has applied, told me he had failed his A-levels.

He said: "Although I was trying to push myself, the help from the teachers wasn't there. By the time I finished my education I just wanted to be outside, so I became a labourer".

He hopes for more for his own children, adding: "What I want is for them to be able to do what they want to do...not just have to do a job."

Searching for answers

Nick Clegg, the former deputy prime minister, is launching a cross-party commission with the Labour MP Stephen Kinnock and Conservative MP Suella Fernandes to investigate why the regional inequalities exist and how they can be addressed.

Nick Clegg is launching a commission to examine regional inequality

He believes that while Liberal Democrat policies like the pupil premium did help address the economic gap - they did not cover this regional issue.

He said: "By focusing strictly on socio-economic inequality, policymakers like myself have been preoccupied with just one part of the problem.

"What is now becoming clear is that inequality in education comes in many shapes and sizes. It is not just the relative wealth of parents that holds large numbers of bright kids back, it is postcode inequality too.

"What part of the country a child grows up in has a real impact on their life chances."

- Published22 January 2015

- Published2 November 2015

- Published30 June 2014

- Published21 February 2013