10 charts that show the effect of tuition fees

- Published

University tuition fees in England have become a political battleground - with renewed calls that they should be scrapped.

When they were increased a few years ago to £9,000 they became a literal battleground, with activists clashing with police on the streets around Westminster.

Now they are going to rise again. But what has the impact of higher fees been? Have they cut student numbers? And are they worth the money?

1. How do England's fees compare with other countries?

Students in England leave university with higher debts than almost anywhere else in the developed world, the Institute for Fiscal Studies said this week.

Charging £9,250 a year for an undergraduate degree makes England a real outlier by international standards.

It's even an outlier in the UK, where Scotland has no fees for Scottish students, and fees in Wales and Northern Ireland are much lower.

Much of Europe still sticks with low fees or no fees - and Germany, which used to charge fees, has scrapped them.

There are also lower costs in many European countries where many more students live at home.

The only country with comparable fees is the United States.

But the US is not a straightforward comparison because courses are four years rather than three and any "average" covers a hugely diverse market.

Top private colleges can charge more than £30,000 per year while state colleges can charge local students less than fees in England.

Tuition fees have been abolished in German universities

The University of Washington has lower annual fees than the University of Wolverhampton and until the pound's value slipped, fees would have been cheaper at UCLA in California than UCLAN in Preston.

In New York state, with a population bigger than many European countries, fees are being scrapped for families earning less than about £100,000.

But there is another very important aspect to all this - England's system requires no money up front and repayment depends on earning at least £21,000.

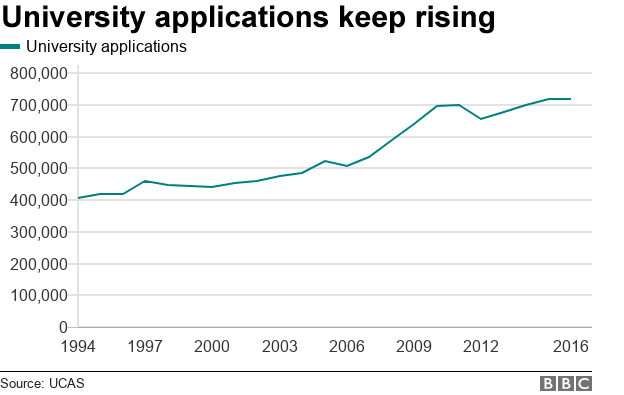

2. Have higher tuition fees deterred people from applying?

Not in the long term.

Student numbers have increased relentlessly, regardless of funding changes, fees and economic ups and downs. It represents a huge aspirational demand for higher education.

It's easy to forget what a massive change this represents.

In 1980, there were only 68,000 people starting university - this autumn there will be more than 500,000. Twice as many people are now getting a degree as were getting five O-levels in the early 1980s.

Applications have dipped only three times - on each occasion when fees were introduced or increased - but they have always recovered.

And one of the main arguments in favour of fees has been that such wide access is unsustainable unless students make a contribution to the cost.

In the early 1980s only about one in six young people could expect to go to university - now, for girls at least, it's over half.

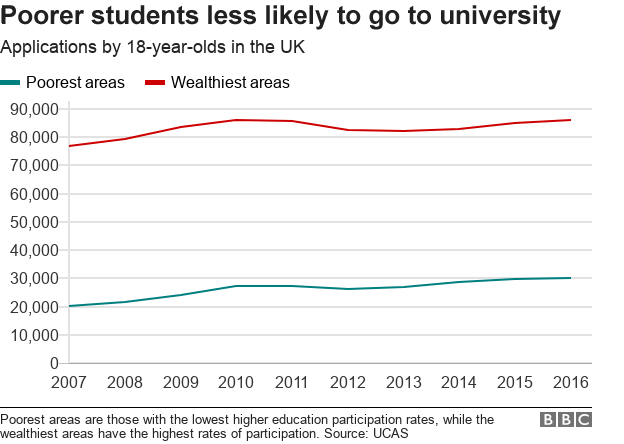

3. Have higher fees closed the door to poorer students?

Students from all backgrounds are more likely to go to university than ever before - including the poorest.

There are different ways of identifying disadvantaged students - either living in areas where few people go to university, having been eligible for free meals at school or under measures of multiple deprivation.

And they all show the same pattern - more of these youngsters are going to university, with the numbers rising through the years of fee increases.

But there is another important dimension to this. Poorer youngsters are still much less likely to go to university than their better-off classmates.

There is a brutal economic symmetry to this. Each upward notch in affluence is linked to a higher entry rate into university.

There are also significant cross-currents of gender and geography. Women are 35% more likely to go to university than men, and youngsters in London are more likely to go to university than anywhere else in the UK.

There are ethnic differences too, with poor white men, in places such as north-east England, the least likely to get university places.

A tuition fees protest, London 2015

4. Students will graduate with debts of more than £50,000

Fees are going up to £9,250 and interest rates on loans are rising to 6.1%, which will push up average student debt on graduation to more than £50,000, including maintenance loans.

The clock on interest charges starts ticking as soon as students begin their course - and it means that they will have run up £5,800 in interest charges before they have even left university.

A high-earning graduate could pay back £40,000 in interest charges, on top of repaying the amount they have borrowed.

These figures could go even higher. Interest rates are linked to inflation and if that begins to rise, then so will the amount charged for repayments.

5. The overall amount of student debt has doubled in four years

The rapid increase in tuition fees - trebling in 2006 and then trebling again in 2012 - means that the amount of outstanding debt has soared.

The figures from the Student Loans Company show the debt level has almost doubled in four years and will continue to climb if fee levels and interest rates rise further.

But about three-quarters of students will not repay their debts in full before the 30-year limit when the loans are written off.

The government wants to sell off student debt to private investors and has begun looking for a buyer for pre-2012 loans.

If this is achieved it will mean another big step away from the idea of universities receiving direct public funding.

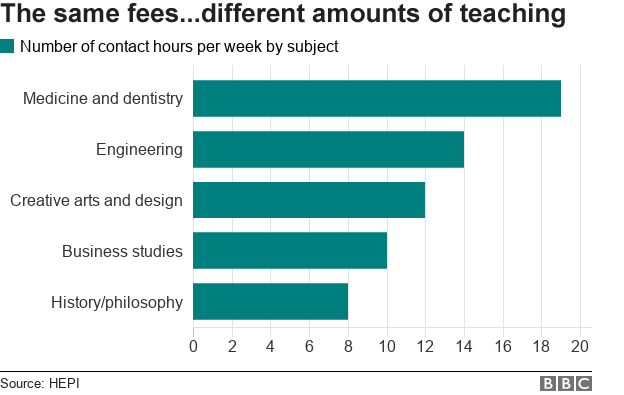

6. Are some students' fees cross-subsidising people on more expensive courses?

At most universities, no matter what course you are following, the level of fee is likely to be the same flat rate of £9,000 (soon to be £9,250).

But the cost of delivering costs is going to vary widely.

Science courses need more expensive equipment and courses such as medicine are going to get much more teaching time and personal instruction.

As the chart shows, subjects such as history will have significantly fewer classroom hours. But there is no recognition of this in the fees system.

According to the Institute for Fiscal Studies, raising fees to £9,000 brought universities 25% more funding per student. But for arts and humanities, they made an extra 47% on each student.

More on tuition fees

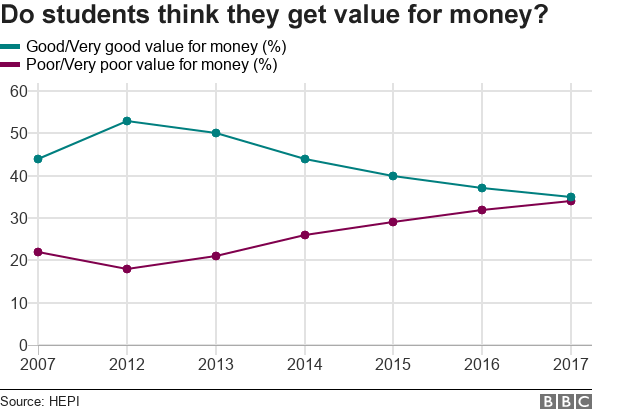

7. Students are less convinced they're getting value for money.

A lack of teaching hours - and a lack of information about how tuition fees are spent - are among the factors that have seen a plunging level of students thinking they're getting value for money.

The chart shows an annual tracking of student attitudes, which in recent years has seen a steady fall in satisfied customers and a rising level of discontent.

Five years ago, 53% of students across the UK thought university was "good" or "very good" value - but this has now slumped to its lowest level of 35%.

Students getting more hours and with expectations of high future earnings, such as medicine, were most likely to think they were getting good value for money.

Least convinced about the value were business and social studies students.

The Higher Education Policy Institute, which carried out the survey, says the quality of teaching is a key factor in perceptions of value.

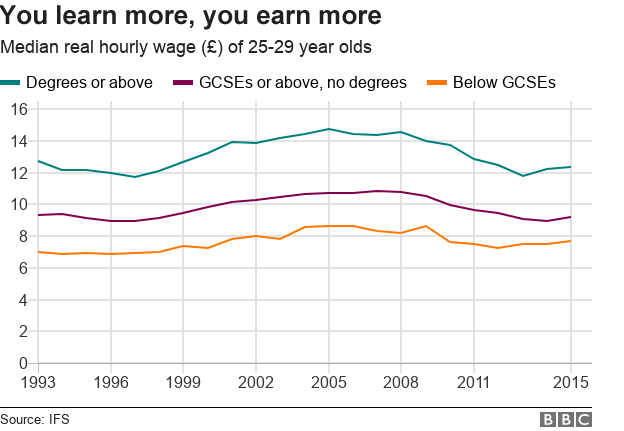

8. Will the cost of fees be returned?

Everyone has heard a story about someone getting a degree and then ending up in a job that didn't need such qualifications. And there are stories of millionaires who never bothered with college.

But all the evidence suggests a relentless link between level of qualifications and future earnings.

As the chart shows, that is the case at every level of education.

According to the OECD, there is no sign that the increase in graduates will take away the financial advantage. Having a degree means better pay and a lower likelihood of being unemployed.

And the stories about maverick billionaires who never went to college are the exception rather than the rule, as an analysis of billionaires' education showed that they are usually highly educated and more likely to have two degrees than no degree.

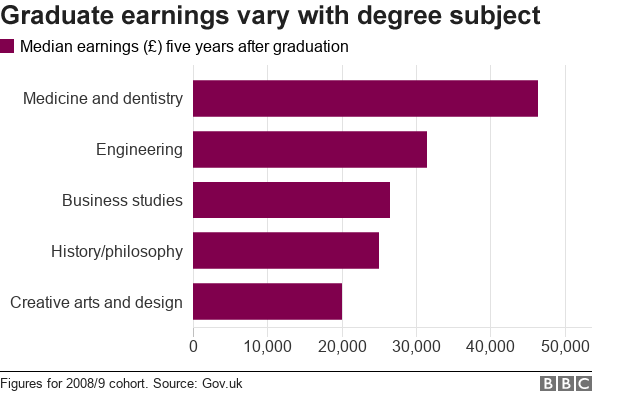

9. Graduate earnings depend on degree subjects

The question of "value" from a degree isn't just about a monetary return. There's a much wider social and cultural dimension.

But even in narrow financial terms, the relationship between the cost of fees and earnings is not straightforward.

For example, there are big differences in the future average earnings between people who studied for medicine and those who took media degrees, even though the annual fee might have been the same.

Medical students pay the same as arts students although their projected earnings are often far higher

Degrees from top-ranking universities can also convert into greater earning power and class of degree is another factor.

And any calculation of financial return on fees will be a combination of factors - what you studied, where you studied and the current demand in the jobs market.

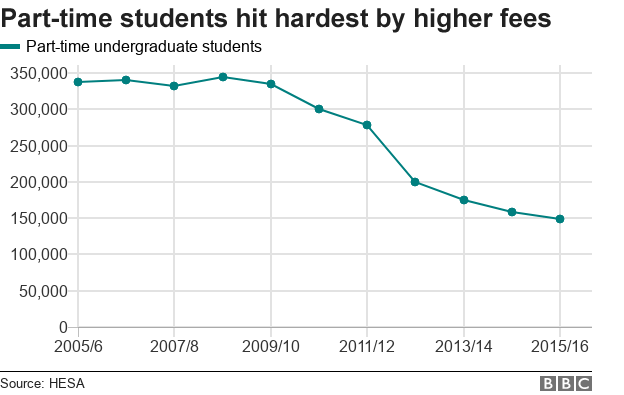

10. Have part-time students been the real losers from fees?

The political attention over tuition fees has focused on the impact on young people taking undergraduate, full-time degrees.

But the biggest change, often overlooked, has been the collapse in part-time students.

These were often adults with other responsibilities who were more sensitive to increased costs.

And the recession saw a big reduction in firms willing to pay for their staff to take qualifications.

There have been repeated warnings from industry about a skills gap, but there are few signs of any recovery in part-time student numbers.

More charts

Data research by Eleanor Lawrie and Catherine Bean