Will tuition fees be scrapped or saved by university review?

- Published

Who should pay for university remains an expensive challenge for governments of all parties

The launch of a "major review" of university tuition fees is expected in the next few weeks - despite speculation that it was going to disappear into the political black hole of a minority government consumed by Brexit.

It will set out the terms of reference for a re-examination of one of the most controversial and combustible areas of policy, which has proved a thorn in the side of all three major political parties in England.

Prime Minister Theresa May, under pressure to respond to Labour's promise to scrap fees, announced a review of "university funding and student financing" at her party conference.

The government might have wanted to reconnect with younger voters, but it seemed to kindle little enthusiasm within its own Department for Education - and the fees overhaul was talked down until it seemed to be disappearing.

'Putting money back'

But it now seems to be back on the agenda - as a big idea on the domestic front, for a government pegged down by interminable Brexit negotiations.

"We have listened and we have learned," Mrs May told her party, with a promise to freeze fees in England at £9,250 a year while the review was taking place.

Theresa May said of fees: "We have listened and we have learned."

There was also an increase in the amount that graduates could earn before having to repay loans, rising from £21,000 to £25,000 a year.

The intention, said Mrs May, was "putting money back into the pockets of graduates with high levels of debt".

And there are precedents for such big reviews of fees going ahead at times of political fragility.

The last two big policy reviews of university funding were begun ahead of general elections in 1997 and 2010 and were completed after changes of government and prime minister.

So what will be the options under scrutiny from the review?

Cut fees or scrap fees: The policy of raising charges every year with inflation was scrapped before it was even introduced this year. It seemed to reflect a sea-change in attitudes towards rising fees, brought into sharper electoral focus by Labour's success with the student vote.

The prospect of average student debt rising above £50,000 sent a shiver down the spine of middle England.

There were newspaper reports suggesting that the government was considering lowering them to £7,000 a year. And there will be great political pressure to do something to reduce the headline price.

Graduate tax: Even if tuition fees were scrapped, it would not make university free: someone would have to pick up the cost. The taxpayer could pay for it all - or graduates could be asked to repay through their tax.

Change the language: Even though there has been hesitation about a graduate tax, it does show there does not need to be a price tag on the cost of tuition. Graduates, over their working lives, will pay for many services through tax without any fixed headline cost. For example, the future amount that a graduate will pay towards the NHS through income tax will not be seen as a "debt".

Interest rates: There will be a hard look at the interest charges on loans, currently up to 6.1%.

Maintenance grants: There will be a strong lobby for a return to grants for disadvantaged students, rather than the repayable loans that replaced them.

Variable fees: There have been calls for fees to be more directly linked to likely future earnings, so that students would pay less for courses in which they might expect to earn less. This would resisted by universities that would see some subjects or institutions being stripped of funding. Others have called for means-tested fees.

Value for money: Disputes over vice-chancellors' pay have highlighted the much greater need for students to feel they're getting value for their fees, over issues such as teaching hours.

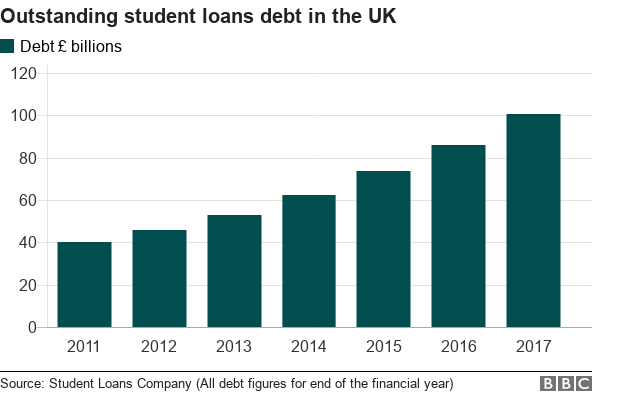

Selling student loan debt: There will be calls to end the sale of student-loan debt to private investors. Debt levels passed the £100bn mark this year - and there have been challenges to privatising this debt.

'Buy back debt'

On the sale of debt, Estelle Clarke, former City lawyer and adviser to the Intergenerational Foundation think tank, has an idea that puts cat among the pigeons.

She has called for a "right to buy" for graduates to be able to buy back their own student loans at the same reduced price at which they will be sold to investors.

The argument, in a paper for the Finance and Society journal, external, is that if the government can sell student debt to private investors, why not offer the same terms to the student, who will have to spend decades paying off the debt?

"That the government is prepared to sell student loans to wealthy investors for a price that reflects a fraction of their value shows a profound disconnect between government and the people," says Ms Clarke.

The radical idea has been backed by Professor Sir Keith Burnett, vice-chancellor, of the University of Sheffield.

"Education feels to many like a burden as well as a liberation," says Sir Keith.

"Higher education is now the subject of fierce party-political debate, and some believe it could decide the outcome of the next election," he says.

'Dramatic increase in investment'

But there will be voices calling to keep the current system in place - and the Department for Education will be unlikely to provide any propulsion for change.

A report this week from the Centre for Global Higher Education, based at the UCL Institute of Education in London, said that the introduction of tuition fees had made the system better funded and able to expand to provide places for more students.

The study said that fees had meant a "dramatic increase in investment" in per-student funding - with university budgets no longer having to depend on governments with more pressing priorities.

The fee system has been defended as a sustainable model for university funding

Dr Gill Wyness, co-author of the study, said the current fees and loan system "keeps university free at the point of entry, and provides students with comparatively generous assistance for living expenses, while protecting low-earning graduates from the risk of high repayments".

But the study highlights that this is as much about perception as economics, and "the system is still poorly understood by students".

The OECD's influential education chief, Andreas Schleicher, is also an advocate of England's fee system.

Speaking at the Education Policy Institute in London this month, he said that it provided sustainable funding for universities, in contrast to many European systems where expansion was being held back by underfunding.

Mr Schleicher said the system of fees and loans was "years ahead" of other major economies.

Ahead of its time? Or a fee that has run out of time? The debate is about to begin again.

- Published8 July 2017

- Published13 July 2017