Hate mail and firebombs: How women won the vote

- Published

"I am glad to hear you are in hospital. I hope you suffer torture until you die, you idiot."

Signed "an Englishman", this piece of hate mail was sent to votes-for-women campaigner Emily Wilding Davison as she lay dying in hospital in June 1913.

Days earlier, she had been trampled by the King's horse after ducking on to the track in a protest at the Epsom Derby.

She never regained consciousness and her death on 8 June is regarded as a key point in the votes-for-women campaign.

The letter is among hundreds of rarely seen documents made accessible to students on a new free online course,, external marking 100 years since the first women gained the right to vote in the UK.

The course timing is "hugely appropriate", and the content "so relevant" given current debates on the gender pay-gap and sexual harassment, says its leader Claire Kennan of Royal Holloway, University of London.

The letter shows today's trolling of female academics, MPs and other public figures is nothing new, she says.

"It just so happens that now this is done on social media platforms rather than through letters.

"There are so many parallels here."

The 100-year-old votes for women posters

New coin marks 100 years of voting

"The idea is that we wanted to take the learners on a journey with me as I go and discover of history of the women's suffrage movement," says Mrs Kennan.

"It's not just sitting listening to a video of a lecture, there are very short sharp documentary-style interviews - which makes it accessible and a lot more interesting and engaging than a traditional course."

Students will learn about the "splits and splinters" in the suffrage movement, with many organisations preferring peaceful campaigning and rejecting the "deeds not words" approach adopted by Emily Wilding Davison and her allies in the Women's Social and Political Union, led by Emmeline Pankhurst.

"Without the militant action we probably wouldn't have got the vote as early but we mustn't forget the peaceful constitutional methods of protest," says Mrs Kennan.

Millicent Fawcett preferred to campaign within the law

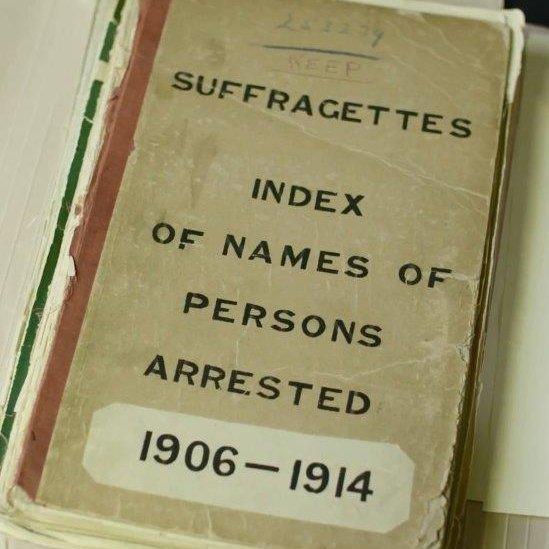

Documents from the National Archive at Kew detail how the state kept tabs on the suffrage campaigns, the protests and the attacks on property.

Windows were smashed, telegraph wires cut and chemical bombs put in letter boxes. There was even a bomb at St Paul's Cathedral which failed to go off.

There are the official records of the costs of repairs, as well police arrest lists and first-hand accounts of the violent force-feeding of women protesters who went on hunger strike in prison.

There's also access to the London School of Economics Women's Library collection, which holds the personal effects that Emily Wilding Davison had on her on Derby Day, including her race programme and her return train ticket.

And another letter, sent to Emily while she was in hospital, this time from her mother.

"I feel I must write to you. I am in a terrible state of mind at the news which reached me last evening.

"I cannot realise that you could have done such a dreadful act, even for the cause which I know you have given up your whole heart and soul to - and it has done so little in return for you.

It is signed: "Oceans of love, Mother." But Emily was never able to read it.

The 1918 Act

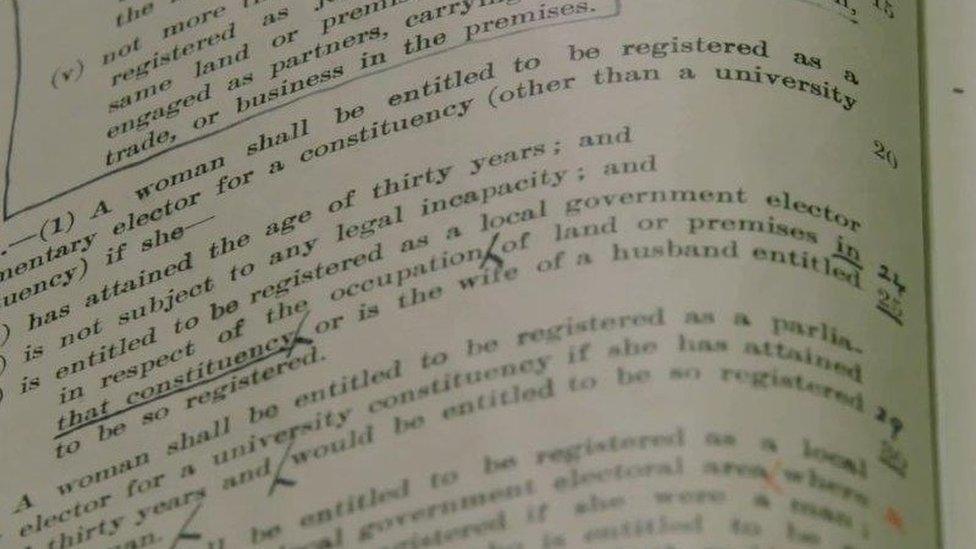

Students can also look at copies of the 1918 Representation of the People Bill, which proposed granting the right to vote to property-owning women over 30, as it went through Parliament.

"They were literally sticking these amendments in by hand and working out what the Act would say," says Mrs Kennan.

Course leader Claire Kennan (R) in the UK Parliament's Original Act Room with senior archivist Mari Takayanagi

She found putting the course together "incredibly eye-opening".

It showed her "just how much my predecessors have done".

A long battle

The first mass petition backing votes for women was presented to Parliament in 1866.

But it took until 6 February 1918 for the law to change for some women, and only in 1928 did women finally gain equal voting rights with men.

Nancy Astor was the first female MP to take her seat in the House of Commons in December 1919.

The archive shows male MPs did not make her particularly welcome - but very slowly, Parliament began to take issues important to women into account, says Mrs Kennan.

"Things like the tampon tax are now discussed in Parliament, issues around childcare... but there's still a way to go."

She hopes the three-week course will attract a wide range of people, including those who might not otherwise consider higher education.

"It's so important that we encourage a dialogue about the history of women's rights.

"It's not something that's taught widely... charting the process of protest, liberty and reform, women's rights, workers' rights and minority rights."

And there's a message in the history of the long struggle for votes for women for today's equal rights campaigners, she says.

"Don't give up... It's been a long battle and there's still a way to go... but we have come a long way and that's why we need to remember these women."

- Published22 January 2018

- Published18 January 2018

- Published14 January 2018

- Published4 December 2017

- Published8 March 2017

- Published6 November 2015