Jacob Rees-Mogg says heckling good for politicians

- Published

Jacob Rees-Mogg said masks were sinister, but protests were part of political life

Jacob Rees-Mogg said that heckling can be good for politicians making a speech, in evidence to a parliamentary inquiry into free speech in universities.

The Conservative MP faced protests last week when he spoke at the University of the West of England.

But he said that the wearing of masks by demonstrators was more "sinister".

Sam Gyimah, the Universities Minister, earlier warned of a "creeping culture of censorship" on university campuses.

Mr Rees-Mogg told the Human Rights Committee that "people shouting and heckling" is part of political life.

"To be perfectly honest, as a politician a bit of heckling can make your speech. It can actually be very good for the speaker rather than damaging."

Online abuse

He said that protestors at the event in Bristol were trying to stop him speak, but there was no threat of violence until there were claims that one of the demonstrators had been hit.

Apart from the masks, he said the protest was "perfectly legitimate" and only a little "pushy".

Jacob Rees-Mogg faced protests at the University of the West of England

"As a politician you should expect that people may come and heckle and that not everybody is going to want to sit there quietly and listen to my view of the world," said Mr Rees-Mogg.

"As MPs, we can hardly complain considering the noise we make in the chamber of the House of Commons."

The committee is investigating claims that free speech is being inhibited in universities - and Mr Rees-Mogg told them the protest he faced was much less worrying than the "online abuse" faced by some female MPs.

Sam Gyimah said students should not be "mollycoddled" away from difficult subjects

The Conservative MP said he feared "self-censorship" from universities, who might not want the "hassle" and expense of inviting speakers who might be controversial.

Mr Gyimah, the universities minister, had told the Human Rights Committee that a culture of intolerance was spilling over from social media.

"There is a section within our universities that think you can restrict free speech.

"If what you're doing is essentially mollycoddling someone from opinions and views that they might find offensive, then that is wrong."

Any evidence?

But Harriet Harman, who chairs the committee, questioned whether there was evidence of free speech being eroded.

Concerns about threats to free speech in university had been widely publicised, but that was not the same as providing evidence, she said.

Harriet Harman asked for evidence to back claims of free speech being limited at university

Mr Gyimah said he thought there was a growing problem in universities of groups trying to stop others from expressing ideas - although specific evidence could be "difficult to gather".

He said there had been protests over speakers on topics such as Israel and issues of religion, sexuality or political belief.

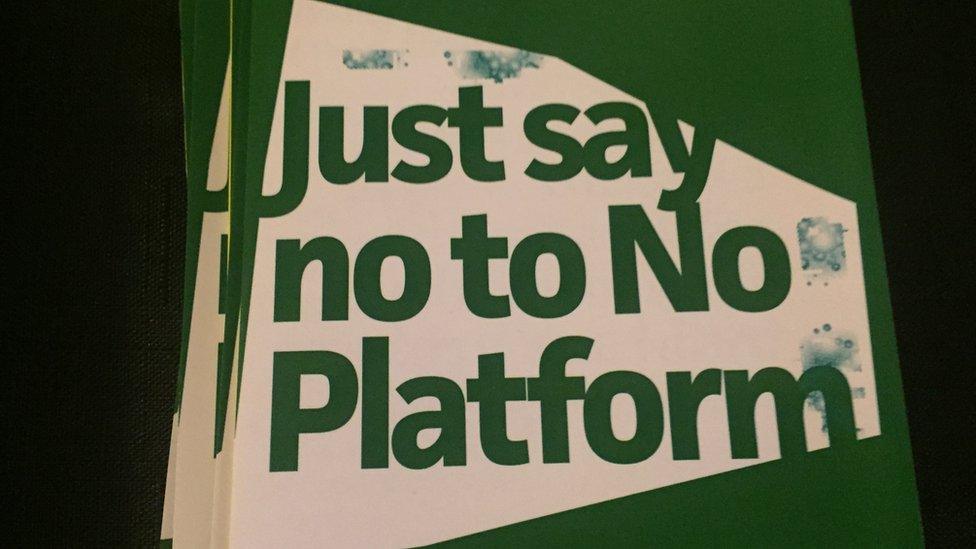

There have also been concerns over "no-platforming", where people are prevented from speaking - but members of the committee pressed Mr Gyimah over whether there was any proof of this being a widespread problem in universities.

'Freedom of speech not absolute'

The committee is also considering whether the Prevent counter-extremism strategy stops students from discussing some controversial subjects.

Ben Wallace, Security Minister, said there was "no real evidence of free speech being curtailed by Prevent".

Ben Wallace, Security Minister, said it was a myth that Prevent was curtailing free speech

"We have struggled to find evidence of actual events that have been cancelled."

But Mr Wallace said: "Freedom of speech is not absolute." For example, it was not lawful to incite racial hatred.

He said that Prevent was a response to an authentic problem, of people being radicalised on campus.

Radical Islamists were still recruiting in "educational settings" and 23,000 people in the UK were currently considered security concerns with an "extremist mindset", he told the committee.

But MPs and peers on the committee questioned whether there was enough guidance to make a clear distinction between legitimate, strong views and unlawful violent extremism.

They raised concerns that even if events had not been cancelled, there could have been events that were never even proposed, because of fears over being referred to Prevent.

In December, the previous Universities Minister, Jo Johnson, warned that universities that failed to uphold free speech could face fines from the new regulator, the Office for Students.

Earlier this week, the Prime Minister, Theresa May, said: "In our universities, which should be bastions of free thought and expression, we've seen the efforts of politicians and academics to engage in open debate frustrated by an aggressive and intolerant minority.

"It's time we asked ourselves seriously whether we really want it to be like this."

- Published10 January 2018

- Published26 December 2017

- Published26 February 2016