'No exams but I knew I wasn't thick'

- Published

Maxine left school without qualifications but went on to become a tutor

Maxine Turner left school without a single qualification.

"But I knew I wasn't thick," she says.

She went on to get a teaching qualification and now she's running education courses trying to help adults without qualifications, without jobs and often drained of self-confidence.

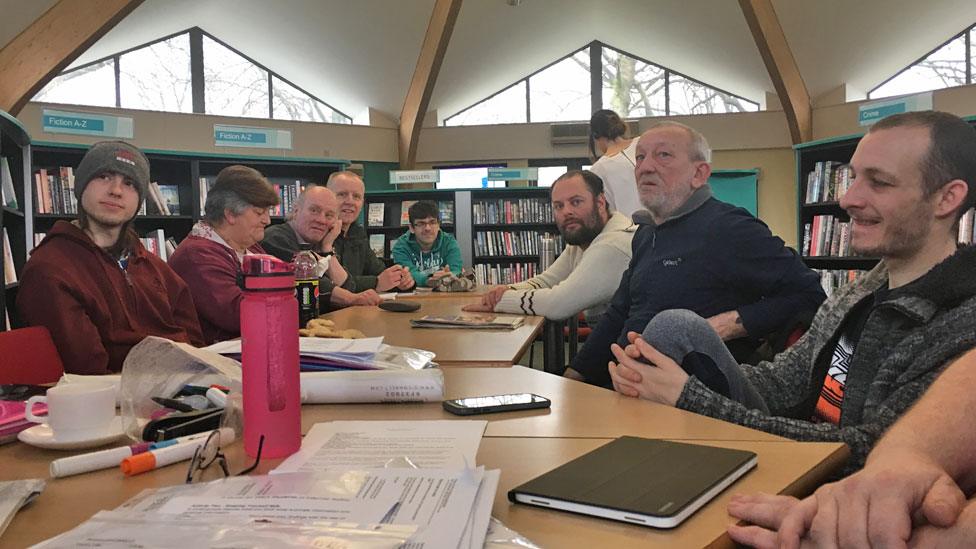

Maxine is speaking at Mowbray Gardens Library in Rotherham, South Yorkshire, where a group is gathering for lessons taught by the Workers Educational Association (WEA), the largest voluntary sector provider of adult education.

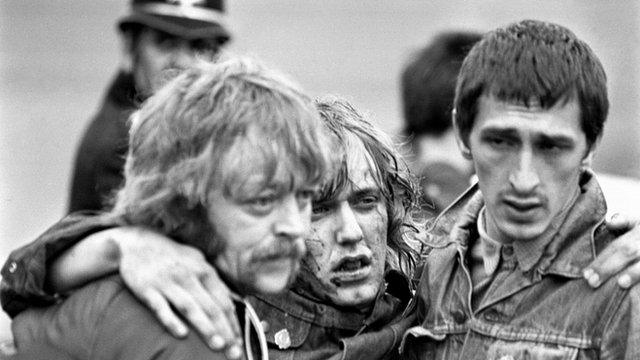

There are ex-miners here who haven't worked since the pits closed in the 1980s.

"We all need respect. Everyone should have a chance," says Shane

When Maxine left school in the 1970s, she says working class youngsters were expected to go straight into factories, mines or the steelworks. They didn't need to take exams.

"Maths may as well have been taught in Martian language," she says.

'A kind of malaise'

But those industries have declined and communities have been left behind.

"There's a kind of malaise that falls over like a blanket. It's really hard to break through," says Maxine, who found her own way back into learning through the WEA, where she became a tutor.

There have been endless policy announcements and glossy strategies about improving vocational skills and helping people to retrain.

But how does that really translate at the sharp end?

It's tough enough for people with qualifications - imagine what it's like without any exams and your only work experience is in jobs that no longer exist.

"We all need respect. Everyone should have a chance," says Shane, who is part of the student group.

"I felt like a proper lost cause," says Laura

He doesn't want anyone looking down their noses at people trying to find work or training for a fresh start.

Students talk of feeling "belittled" by an often faceless online application process.

These are the disenfranchised white, working class. Not working, but at least back in class.

'Communities aren't there any more'

At the weekly lesson, they're being taught IT skills that could help them write an application letter, put together a CV or find ways to access information online.

It's also about working as a group.

The classes are run each week in the library in Rotherham

There are repeated comments about the threat of social isolation in areas where there are shrinking numbers of shared places to be together.

"People lived, drank, worked together. But those communities aren't there any more," says Maxine.

Richard, in his 40s, says he'd been living more or less like a "recluse", sometimes struggling with depression and finding it difficult to get out of the house.

This WEA class had given him a sense of purpose and friendship, as well as learning.

The need for retraining is profound.

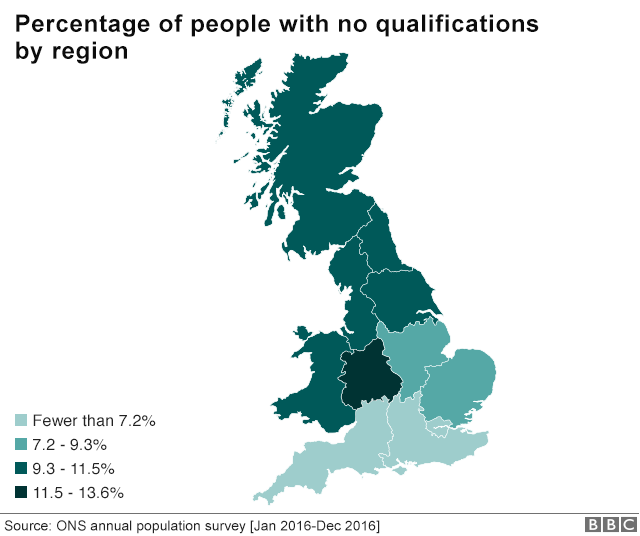

North-south divide

In Rotherham, 12% of the working-age population have no qualifications - in Surrey it's 4%, in parts of London it's too low to be measured.

It's a problem that is markedly worse across the north of England compared with the south.

London represents the other end of the spectrum, with the highest concentration of graduates anywhere in Europe.

For those who find work in Rotherham, the typical full-time annual salary in the town is about £25,600.

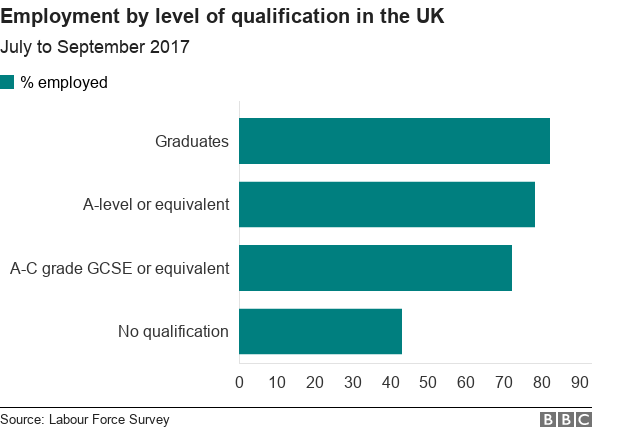

The news agenda has been focused on value for money for university students, but it's those without qualifications who are almost twice as likely not to be working.

The WEA runs 8,000 adult courses per year - with a very different social profile from the debate about university access.

Among their students, almost half have no or almost no qualifications, almost 40% live in the most deprived areas, a quarter have health problems and 12% have mental health difficulties.

But it's also where education can make the biggest difference.

Miners' strike in south Yorkshire: The industries and communities have disappeared

Research into the impact of WEA courses has shown big improvements in employability and positive benefits for those with mental health conditions.

Parents reported being more confident with helping their own children to learn.

However, it's an uphill struggle. Inside the library there are three separate adult education courses taking place, but the back windows seem to be pitted with what look like air-rifle impacts.

Whether or not that's the cause, it seems an appropriate metaphor for people trying to improve but being assailed from every side.

Parents learning together

In York, another WEA group is gathering. This might be an historic, picturesque city, but it's a tourist economy with lots of insecure, low-paid work.

Its schools have the lowest level of per pupil funding in England.

Parents in York are returning to learning themselves through projects in schools

The group here are taking part in a project where parents learn about helping in school and are encouraged to improve their own skills.

"When you've got a child, but you don't have the financial backing, it's very difficult to get training," says Annemarie.

"I struggled at school with the academic stuff, my self-esteem was very low. I felt stupid. That's what I told myself. I stopped trying because it felt so hard to try."

But she says her confidence has been reinvigorated by her return to lessons.

You may also like:

"I was that scared. I was shy, this awkward person. I felt like a proper lost cause," says Laura, also on the Helping In Schools course.

"I left school when I was 14, I didn't gain any GCSEs. I thought this is me, this is all I have to offer.

"But with this course, I've proved I can still do something.

"Now I feel like I can go on to other things."

Richard says there are many people who have little chance of work and are living like "recluses"

Applying for jobs left her filled with a sense of "not being good enough".

"You think you're going to be turned down straight away."

She spent a long time in her flat, not going out. There are many people like her, she says, "going under the radar".

Now she wants to work with children and is going to study how to help with special educational needs.

Catherine says it was once much easier to get jobs without qualifications

The students and their tutors say the barriers to learning are often practical.

Courses can cost too much or the lack of transport can make them out of reach. Affordable childcare can be the key to returning to learning.

Again and again these students mention the need for confidence and to make learning seem less daunting.

Another student, Catherine, says it used to be much easier to get jobs without qualifications, but now they need to have exams.

"People can do it if they get help," says Laura.

"They throw the tablets at you, but this has helped me more than any medication.

"I feel like my life's been turned around. I want to keep on learning now."

- Published8 February 2018