When truth trumped propaganda in wartime

- Published

The University of London's Senate House building was the wartime Ministry of Information and Orwell's Ministry of Truth

When George Orwell described the "Ministry of Truth" in his novel 1984 he used the University of London's Senate House as his model.

The "enormous pyramidal structure of glittering white concrete" in Bloomsbury had been the Ministry of Information during World War Two.

It was a building Orwell knew well, not least because his wife Eileen O'Shaughnessy worked there in the censorship department.

But there was another secret operation taking place in Senate House.

The Ministry of Information wanted to know what the public was thinking.

How were people responding to the bombing raids? What rumours were circulating? What was really irritating the public?

'We want the truth'

So every day and then weekly, a report was gathered by local intelligence officers across the country, feeding back information to Senate House about what people were saying in pubs, shops, workplaces and air-raid shelters.

When a city was blitzed, the intelligence operation was there soon afterwards listening to what people were saying on bombed streets and the state of their morale.

All these reports, tracking swings in the public mood, are being made available online, external.

A family made homeless by an air raid in 1941 - the intelligence gathering examined whether the public could withstand such attacks

Historian Simon Eliot has been researching this archive of "home intelligence" - and says it fundamentally altered how the war was fought on the home front.

"People were saying, 'We want the truth, even if it's bad. We want to be treated as adults'," said Prof Eliot, who is based in Senate House, in the University of London's School of Advanced Study.

"It quickly dawned on the Ministry of Information that this was critical."

"What comes through very strongly is, 'Don't patronise us, don't treat us as children. We'll feel much better if we know where we stand."

Prof Eliot works in Senate House where the Ministry of Information gathered its daily reports

There was an immediate response from the government and posters which seemed to be implausibly smug or propagandistic were pulled down.

There was an attempt, without divulging military secrets, to be as open as possible in news and to provide accessible information about how and why the war was being fought.

Propaganda leaflets

Prof Eliot says the reports on morale show a remarkable confidence in eventual victory - but also a public that expected to be treated as equal partners.

In the wake of a bombing raid on Portsmouth, the intelligence reports warned of "distrust and indignation", not at the destruction but because the extent of the damage had been underplayed in news reports.

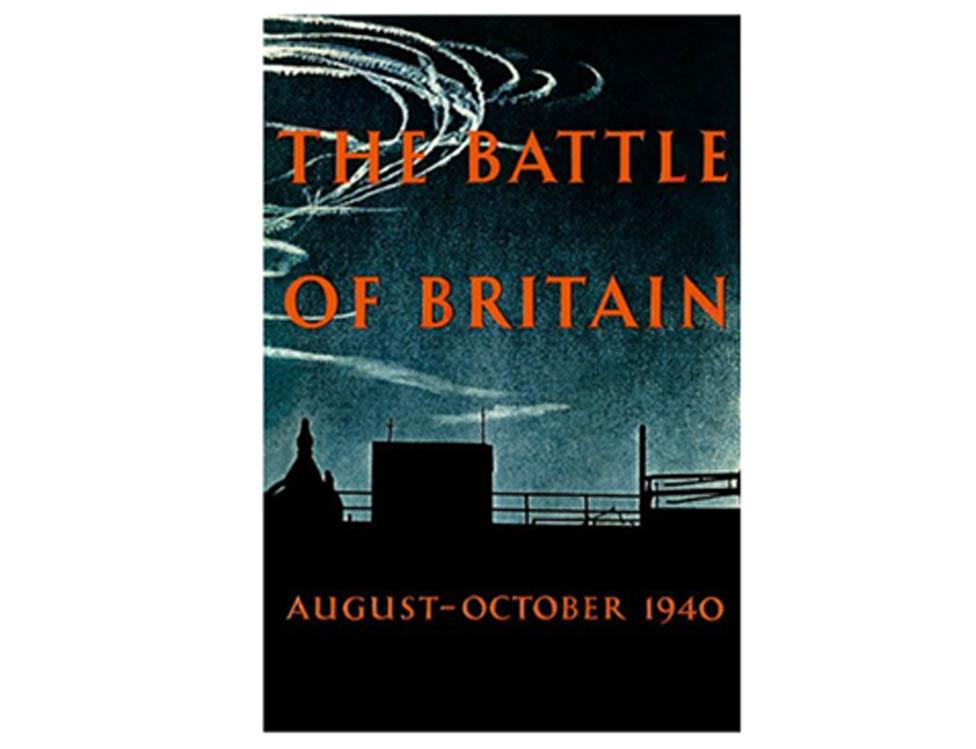

The ministry's information book about the Battle of Britain sold 4.5 million copies

While from a military perspective, there was an instinct to give less information - the reports showed public anger if the severity of attacks, which they had witnessed with their own eyes, seemed to have been glossed over.

When the Nazis dropped propaganda leaflets, people were annoyed when the authorities tried to stop them reading them.

"Not because they would believe them," says Prof Eliot. "But because they liked to hear another view."

'Class bitterness'

There was intense sensitivity about how civilian populations would cope with air raids - but the intelligence reports showed that rather than undermine morale, they seemed to have the opposite effect, hardening resolve and deepening hostility towards the enemy.

But there were tensions. "Class bitterness" was reported with bombed-out people in London's East End threatening to march to the "West End to commandeer hotels and clubs".

There were also concerns about what happened during raids - with reports of "blatant immorality in shelters" and warnings about looting.

George Orwell's novel 1984 showed how dictatorships could stop freedom of expression and replace it with propaganda

The persistence of anti-Semitism was reported frequently. It was explained as a "scapegoat as an outlet for emotional disturbances", but it was enough of a problem to have a separate report commissioned.

This found examples of prejudice against Jewish people, including refugees from Nazi-occupied Europe, in almost all of the 12 regional divisions used by the intelligence services.

The message from the intelligence reports was that war posters should avoid being patronising and talking down to people

But elsewhere there were signs of tolerance.

When the United States entered the war, the ministry found strong public opposition to any discrimination against black servicemen.

'Fire and destruction'

These were secret documents, intended for a very limited circulation, and they could be blunt in their assessments.

"Plymouth as a business and commercial centre of a prosperous countryside has ceased to exist," said an intelligence report after an air raid.

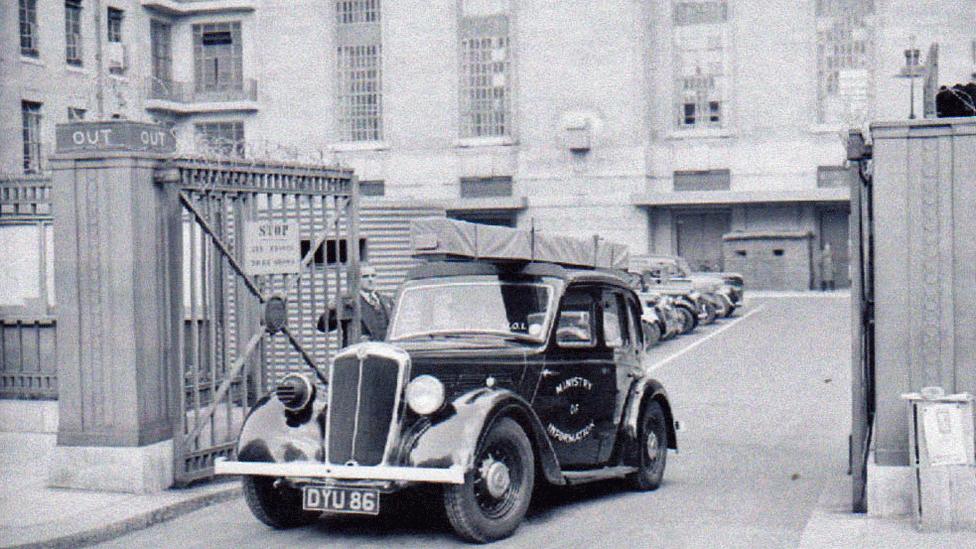

A Ministry of Information car leaves its wartime headquarters in Senate House

"Conditions of living now almost impossible and great feeling in dockside areas of living on island surrounded by fire and destruction," said a report on the bombing of London's docks.

There was great attention to how news was presented.

A BBC News announcer was described as: "Too pompous and heavy, almost as if the Nazis had taken over already."

The intelligence gatherers wanted to know how the public saw the enemy and whether there was an appetite for revenge.

When people saw pictures of French women, accused of collaborating with the Nazis, having their heads shaved by mobs, this went against the public mood.

A report from September 1944 described the response as "sadistic methods of punishment are just what we are fighting against".

'Nuns and parachutists'

With official news being controlled, the intelligence reports focused regularly on the rumours circulating.

There were invasion scares, claims of secret weapons, double agents and disguises and in Newcastle there were stories of messages being written in German on the pavements.

In May 1940, a report wryly notes: "Stories about nuns and parachutists are little in evidence today."

The reports wanted to monitor the morale of people and to know the reality of their experiences

Prof Eliot says that as well as a determination to win the war, the reports show a strong sense of people expecting to win the peace.

He says there are repeated messages about families wanting a better and fairer future.

A report quotes a young man promising that after the war "the old-school tie will be burned at the stake".

Open society

The Ministry of Information, says Prof Eliot, realised that if people thought they were fighting for a more democratic future, this had to be reflected in how news about the war was presented.

It had to be fundamentally different from the dictatorships of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia that shaped Orwell's vision of a Ministry of Truth.

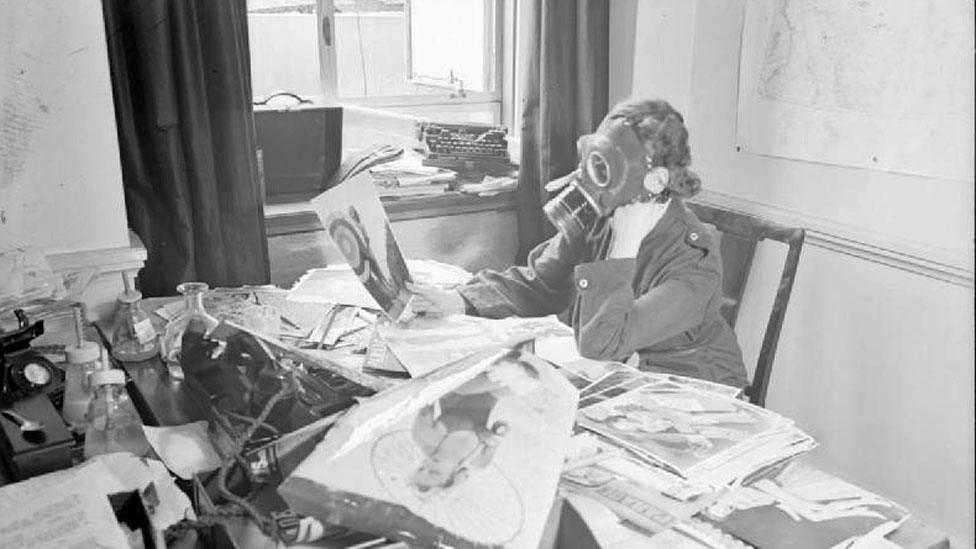

Ministry of Information staff in Senate House showing preparations for an air raid

"It was a case of, 'We've got truth on our side, we're going to use it as a weapon. And we can't do the same as the Germans or the Russians'," says Prof Eliot.

"We are defending an open society - and to an extraordinary extent it remained an open society.

"Their practice was as far as possible to get the information out.

"There was a clear feeling that we were fighting the war for freedom, democracy and the truth - and those things were indivisible."

- Published3 September 2019

- Published18 March 2019

- Published13 November 2015