The ‘taboo’ about who doesn’t go to university

- Published

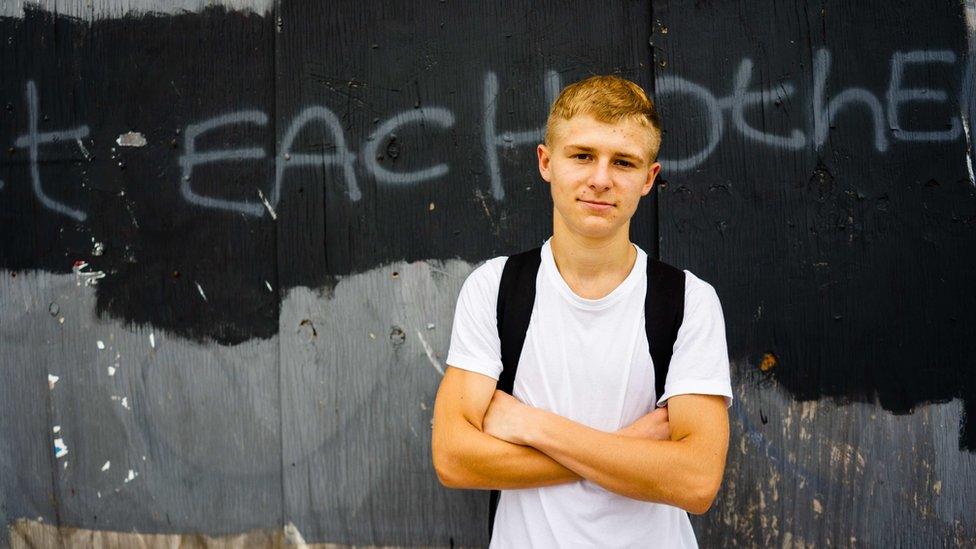

John-Russell Barnes says many of his friends in Hastings remain uncertain about going to university

John-Russell Barnes has three part-time jobs to help support his mother and sisters. But that's not what makes the 18-year-old from Hastings unusual.

He's a white working-class boy who is going to university.

More than half a million new students will be heading off to start at universities across the UK this term, with record numbers set to enter despite all the Covid complications.

But white males from low-income families are the "least likely" group to be going, according to the most recent figures from the Department for Education.

Left behind

Among state school youngsters not on free school meals, 45% go on to higher education by the age of 19. Those more disadvantaged students, eligible for free school meals, have a lower entry rate of 26%.

But for "male, white British, free school meals" pupils, the figure is 13% - even lower than the year before, and to put it in context, it's below "looked after" children who have been in council care and far below those speaking English as a second language.

Coastal towns often have lower rates of young people going to university

This figure of 13% is stuck in another era compared with the success stories of other groups, such as black students, with 59% progressing to higher education, and 64% of Asian students.

For sixth formers in independent schools, 85% make the step forward into higher education.

The gap is so wide that the chairman of the House of Commons education select committee, Robert Halfon, says there has almost been a "taboo" talking about it.

Should I stay or should I go?

But why are young white males from poorer backgrounds so less likely to go to university?

"At the beginning of college a lot of my mates were saying they were going to go to university - and then at the end, they're like 'maybe not,'" says John-Russell Barnes.

"People started to drift off on to different paths."

John-Russell is taking the plunge to go to university in Swansea to study law

That might be a positive alternative, such as an apprenticeship or a good job - but it might also be insecure, temporary work they can pick up in the East Sussex seaside town.

He thinks boys are particularly susceptible to short-term incentives, taking the quick cash available and putting off going to university in a way that means it will never really happen.

"Whereas I feel girls are probably more mature. They're prepared to just go to uni and not worry about it, whereas men are: 'Oh, you know, I'll see how I am in a couple of years and then maybe I'll go.' And they don't end up going."

And in practice it's often easier for men to get better-paid casual labour than women, he says.

Step in to the unknown

John-Russell's own focus has been on studying law, the subject he's going to take at Swansea University after getting the A-level grades he needed at a further education college. He wants it to be a different future from his round of temporary jobs in a bakery, corner shop and pub.

"I've always been quite set on it," he says, and he's been supported by the Villiers Park trust, a charity which works with bright disadvantaged youngsters trying to get into university.

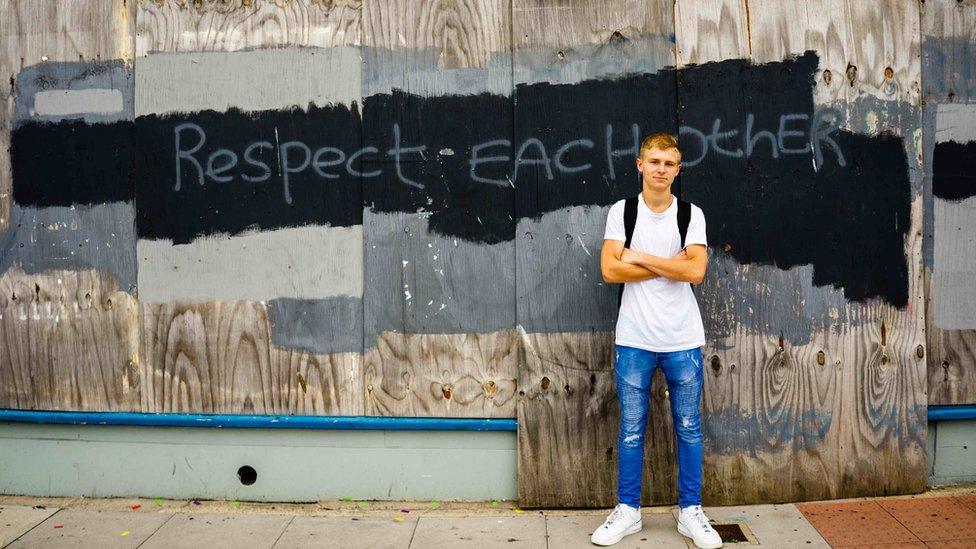

The view from Hastings beach: John-Russell has been working with the Villiers Trust on raising horizons

He's been on projects run by Villiers Park, which provide information, advice and opportunities to meet other young people who are thinking about going to university. And for John-Russell, the biggest deciding factor has been seeing university as the route for his ambition to become a lawyer.

For those of his friends not going to university, he says it's not necessarily the tuition fees that are the main deterrent, but the lack of certainty about getting a career to make the expense worthwhile.

Seaside towns can see holidaymakers, second-homers and deprivation all side by side

There's also the "fear of the unknown", he says, that it's "intimidating" to move into something very different and away from home and family, with no guarantee of a good job at the end.

"Personally I don't really like change that much. It's like going to a restaurant - I always order the same sort of things, rather than trying something new," he says.

It's a big step for him - but he's confident that it's the right decision.

'Imposter syndrome'

But why has this group been so often left behind while others have taken big strides in getting into higher education?

There is nothing inevitable about deprivation being a barrier. Inner London is the most stellar illustration of this, with 49% of pupils on free meals going on to higher education - and overall numbers of disadvantaged students have been rising.

The big factor for John-Russell was seeing university as a path to his ambition to be a lawyer

Women have continued to get more places and accelerated further ahead of men - and boys from middle-class families are able to stay on the conveyor belt that takes them seamlessly from school to university.

And the biggest single increase in university entry over the past decade has been among black youngsters, with black African families doing particularly well. For boys on free school meals from black African families, 52% progress to higher education, compared with 24% for black Caribbean boys on free school meals.

Anne-Marie Canning, chief executive of the Brilliant Club, which campaigns to widen access to university, says there remains a "real issue" about the lack of a similar breakthrough for white working-class boys.

"We need to be more mature about what diversity means," says Ms Canning, a former director of social mobility at King's College London.

She says too often projects to engage this demographic have reverted to stereotypes - with links to things like boxing or other sports which from the outside might seem gritty and male, but which in practice fail to land a punch.

Have changes in jobs and industries dented the confidence of communities?

There are much deeper issues at play with young white males from "post-industrial towns", she suggests.

These are places where the confidence, status and identity of communities have been badly dented by changes in jobs and the economy.

She points to the "collapse of local institutions" - whether it's social clubs, work-based societies, church groups, adult education or trade union organisations, which might once have raised horizons.

"Parental attitudes really matter," she says - and too often such disadvantaged youngsters thinking about applying to university can suffer badly from "imposter syndrome".

Leaving home

There is a strong overlapping regional dimension. The areas of England with a high concentration of white disadvantaged youngsters, such as the north-east, east, south-west and coastal towns, are also where university entry rates are lower.

Sir David Bell, vice chancellor of the University of Sunderland, says universities need to think more about how to present courses to their local community - such as showing clear links into employment and appealing to students who want to carry on living at home.

There are record numbers of students this year - but big regional differences in entry rates

"Social mobility too often is thought of as a relatively small number going away to study and never coming back," said Sir David, a former head of Ofsted.

There have been arguments from the government against getting 50% of young people into university - but in the north-east, where the entry rate for those on free school meals is 21% - he sees this as missing the point.

"It's a nice argument to have in the salons of London that too many people are going to university," said Sir David.

Lack of targets

But what's being done to close the gap?

Graeme Atherton, director of the National Education Opportunities Network, produced research last year revealing that more than half of England's universities had fewer than 5% of poor white students in their intakes.

Instead of this being a call to arms, he says there has been a "perfect storm of inaction".

Only 2% of white low-income males get places in the top group of universities

He has carried out research, so far unpublished, which will show that the numbers of universities with targets for disadvantaged white students are going down rather than up - from 27 institutions to four.

Universities find this a "difficult conversation", he says, and without pressure from policymakers, it's one they often seem to prefer to leave alone.

The low entry rate is in some ways easy to explain. Boys get worse exam results than girls, white students are among the lowest achievers and poor pupils tend to do worse than the wealthy.

It's been been a success story in improving access to universities for students from ethnic minorities

When those factors are combined, white boys from low-income families have among the lowest exam results and are the least well-equipped to get university places.

But Dr Atherton says there are other dimensions.

"We use the term social mobility, but it also means you're leaving something behind, physically and culturally," he says.

Going away to university is a big social departure - and if the rest of the family are ambivalent about its benefits and didn't go themselves, the idea can soon be abandoned.

Even in terms of qualifications, this group can be facing an uphill struggle. They are disproportionately more likely to be taking BTecs rather than the A-levels that will be the more typical path into higher-ranking universities.

Only 2% of white working class boys get into more selective, "high tariff" universities.

MPs warned that delays in BTec grades this summer could have caused even more disruption for students wanting to use the results for university places.

Mary Curnock Cook was previously in charge of Ucas, the admissions system for universities, and she says there has been a reluctance to engage with this issue - which gets left in the "too difficult to handle box".

But she says it's a "double discrimination" if disadvantaged white males not only are under-represented in university, but then have the problem ignored.

Robert Halfon, whose select committee is investigating the achievement gap for these "left behind" young people, says it's important that it's no longer "swept under the carpet".