Election 2019: How significant is immigration to the UK?

- Published

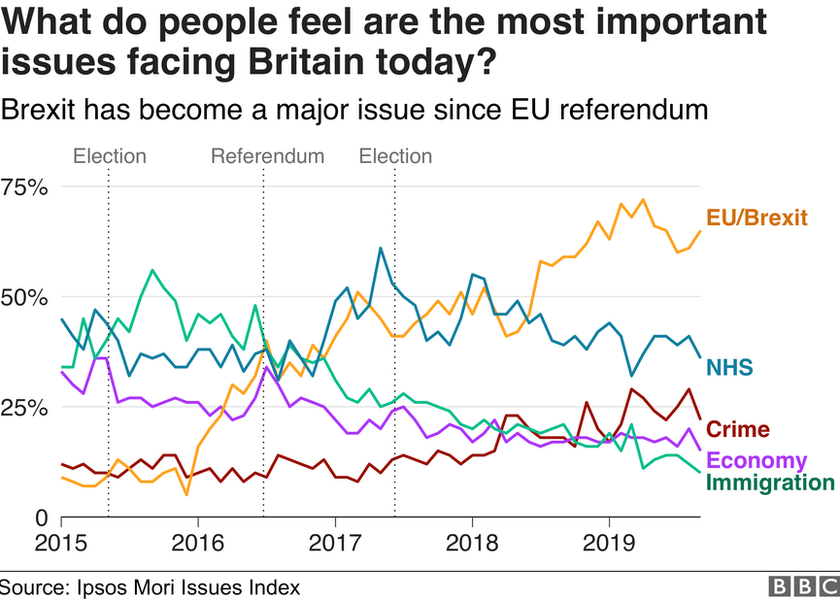

In the lead-up to the 2016 Brexit referendum, polls suggested immigration was seen as the most pressing issue facing the nation, not EU membership.

Today, concern about immigration is far lower,, external even though many of the underlying factors have not changed.

Whether or not we leave the EU, there are a huge number of unanswered questions over exactly what a reformed immigration system would look like.

EU immigration has fallen

For almost a decade, the number of migrants coming to the UK was the primary focus of the Conservative Party.

David Cameron pledged to push net migration - the balance of people arriving minus those leaving in any one year - below 100,000. He failed.

There is no doubt that many who back Brexit hope it will lead to greater control of immigration.

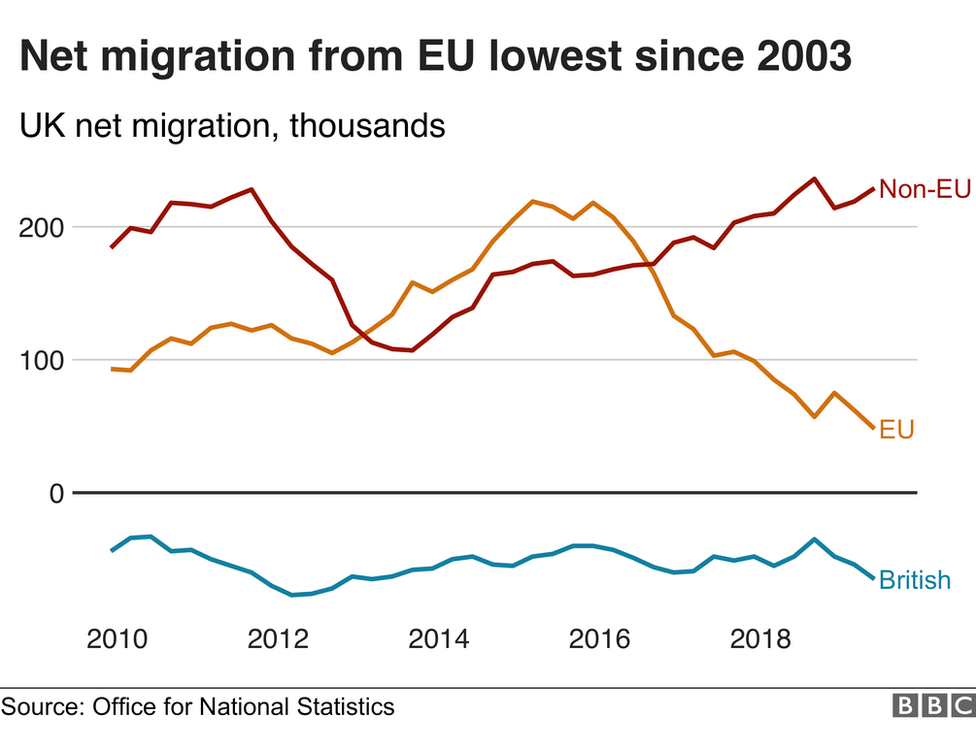

But recent immigration statistics clearly show leaving the EU may not affect the overall number of migrants coming to the UK, because of the continuing economic pull the country exerts on the rest of the world.

In the year to June 2019, an estimated 212,000 more people moved to the UK than left. Within that total, the number of EU citizens arriving was its lowest level since 2003.

At the same time, net migration from the rest of the world has continued to go up and now stands at an estimated 229,000.

'Control' not counting

Migration today is a fundamental part of the British economic landscape, as is the case for every other leading industrialised nation.

This narrative is now being adopted by all the main political parties, although it is being packaged in quite different ways.

Rather than making promises they will never be able to keep on numbers, all of the political parties are promising control and management.

The Conservatives pledge an "Australian-style points-based system" which will end freedom of movement.

In essence, this means that someone's chances of getting into the UK comes down to the skills they can offer. The party says this provides "real control".

The Brexit Party has also pledged to introduce a points-based system, and promised to cut migration to the UK to 50,000, although this figure did not appear in its manifesto.

Proposals for a points-based system are not remotely new. It is a rather staggering 14 years since a Labour government first used these words - but the resulting system looks nothing like the Australian model because it has been constantly tinkered with by successive governments.

So creating an Australian system would be a massive undertaking and could take years to implement.

Everything hinges on Brexit

What's more, the exact shape of this system entirely depends on what happens with Brexit.

If the UK stays in the EU, then freedom of movement remains.

If we leave, the system could be influenced by the trade deals the UK makes with other countries. For instance, the EU or India may hold out on a deal until the UK offers preferential access to their workers.

Labour has not made such an explicit reference to Australia as the Conservatives - but pledges to "recruit the people we need". It says that EU freedom of movement may be "subject to negotiations".

The Conservatives say there will be "fewer lower-skilled migrants and overall numbers will come down". But this raises specific questions for specific sectors of the economy.

What, for instance, would it mean for social care? There are more than 120,000 vacancies in this increasingly crisis-ridden sector. Most potential workers are not classed as skilled, and the problem is said to be getting worse because the weak pound is putting off many would-be immigrant workers.

Labour talks about filling labour shortages. This could mean a very open approach, dictated by business leaders unconcerned about the effect that migration may have on housing and the population.

The Liberal Democrats, meanwhile, explicitly propose taking control of work permits out of the hands of the Home Office and into the Departments for Business and Education. Detractors say this would have the same effect as Labour's policy.

Critics say these proposals also raise the prospect that British workers' wages will be undercut. Labour claims it can stop that through regulation and by targeting labour exploitation more effectively.

CONFUSED? Our simple election guide, external

MANIFESTO GUIDE: Who should I vote for?, external

POSTCODE SEARCH: Find your local candidates, external

Payments and benefits

The Conservatives are pledging a suite of measures - some already existing - which aim to ensure migrants pay their way. The current NHS surcharge - paid on entry - will continue, as will another for "skills".

The party also promises that leaving the EU means European migrants will only be able to access to some key benefits in the way that non-EEA migrants currently do - after five years. It will also stop people claiming child benefit to send to families back home.

Labour, the Liberal Democrats and other parties accuse the Conservatives of running a "hostile environment" for immigrants who should be made welcome. In particular, Labour and the Lib Dems say migrants should have the right to have their family living with them - which means, among other things, ending a complex minimum income scheme that prevents some spouses coming to the UK.

One interesting unanswered question is how the UK counts migrants. At present, the UK is not doing a very good job at doing so, as I have explained elsewhere.

The Conservatives say that after Brexit they will track who is coming in and out of the country. However, implementing such a system has not been stopped by the EU, but a combination of technological failures and cuts.

The UK once had paper records of migrants, but they were scrapped more than 20 years ago. Tony Blair's Labour then promised an "e-Borders" system - but it staggered from crisis to crisis. The Conservative-Lib Dem coalition scrapped that plan in 2010, and to this day there is still no single system in place to count all people in and out.

And that perhaps raises the biggest issue.

Whatever your view of migration, every expert in this field - from former border officers to academics - says the British immigration system has become a total mess over 20 years: underfunded, blown from crisis to crisis amid competing and contradictory policy objectives and implicitly undermined by a lack of consensus as to what the nation wants.