EU net migration to the UK falls to lowest level since 2003

- Published

- comments

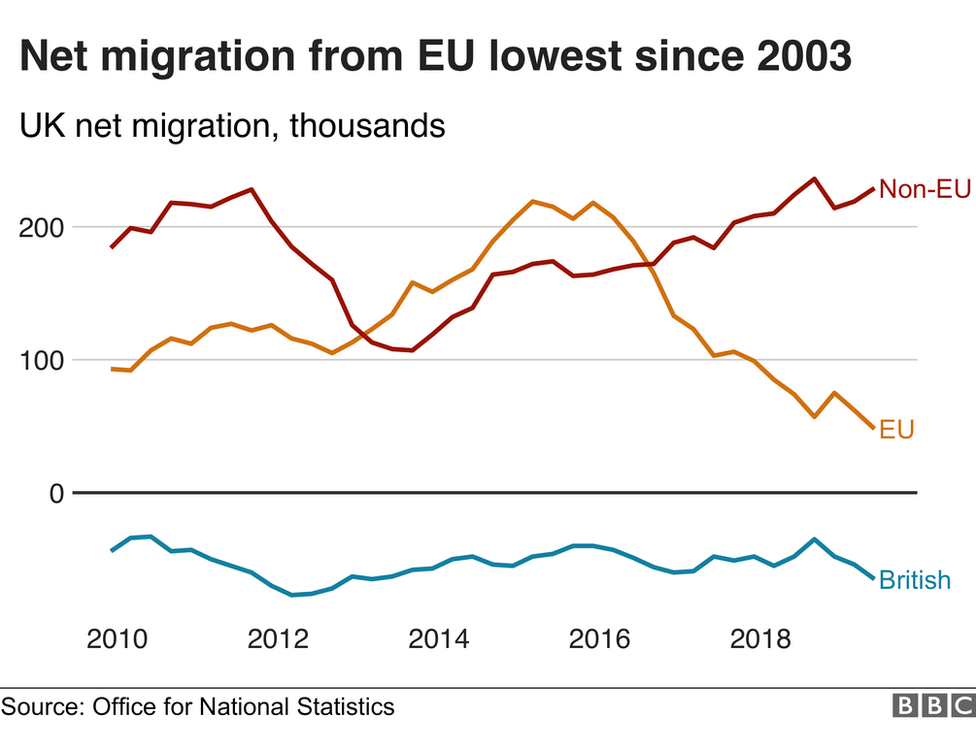

EU net migration to the UK has fallen to its lowest level for 16 years, ONS figures show.

The difference between how many people from the EU came to the UK for at least 12 months and how many left dropped to 48,000 - the lowest level since 2003.

The ONS says this was down to fewer people coming to Britain for work, while a record high returned home.

In the year to June, overall net migration from both EU and non-EU countries was 212,000.

The number of people arriving from the EU now stands at its lowest level since the year ending March 2013, according to the figures published by the Office for National Statistics, external.

The BBC's home affairs correspondent Danny Shaw said there had also been a steady rise in the number of EU citizens returning home - 151,000 emigrated in the past 12 months, double the number six years ago and the highest figure on record.

EU net migration previously hit peak levels of more than 200,000 in 2015 and early 2016.

Meanwhile, net migration from outside the EU has gradually increased for the past six years as more non-EU citizens came to the UK to study, the ONS says.

Migration Watch UK's chairman Alp Mehmet said it was "hardly surprising" that EU net migration had fallen due to Brexit uncertainty.

However, Madeleine Sumption, director of the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, suggested other reasons could also be behind the fall.

She said: "The reasons for this will include things like the lower value of the pound making the UK less attractive, improving economic prospects in EU countries of origin, and potentially the political uncertainty of the prolonged Brexit process."

Immigration figures were reclassified as "experimental" earlier this year after officials said there was "significant uncertainty" about the reliability of recent data.

Since 2016, there has been a decrease in immigration for work while people coming to the UK for study has gradually increased, the report adds.

It says the fall in immigration for work has mainly been because of a decrease in EU citizens coming to the UK looking for work, particularly those from eight of the countries which joined the EU in 2004, including Poland.

The ONS estimated that about 229,000 more non-EU citizens moved to the UK than left in the year ending June 2019.

This non-EU net migration has gradually increased since 2013 as immigration has risen and emigration for this group has remained "broadly stable".

Is this the Brexit effect?

EU immigration has fallen by 85,000 since the 'in-out' referendum in 2016 while EU emigration has increased by 56,000.

It's a steep, clear trend that has taken EU net migration back to what it was before the expansion of the bloc in 2004.

That was when people from 10 nations, including Poland, Hungary, Latvia and Lithuania, were controversially given free movement rights to live and work in the UK.

In some areas, the influx of migrants from this group of countries fuelled concerns about immigration, stoking a wider debate about control of Britain's borders and membership of the EU.

It's ironic, therefore, that just as the UK stands on the brink of severing its ties with the European Union one of the key factors that persuaded people to vote leave may be - in numerical terms at least - diminishing as an issue.

The ONS says the rise in non-EU immigration is mainly because of a gradual increase in those coming to the UK for formal study.

A spokesman for the ONS said: "Our best assessment using all data sources is that long-term immigration, emigration and net migration have remained broadly stable since the end of 2016. However, we have seen different patterns for EU and non-EU citizens.

"While there are still more EU citizens moving to the UK than leaving, EU net migration has fallen since 2016, driven by fewer EU arrivals for work.

"In contrast, non-EU net migration has gradually increased for the past six years, largely as more non-EU citizens came to study."

In response to the figures, business leaders said that ensuring firms had access "to the people and skills they need" was "as important as forging our future trading relationship with the EU".

Matthew Fell, chief UK policy director for Confederation of British Industry (CBI), said "shortages already exist at all skill levels" and that future immigration policy should not only focus on the "brightest and best".

"To build new homes and schools, we don't just need architects and engineers, but bricklayers and plumbers too," he said.

What are the parties promising you?

This concise guide to where the parties stand on key issues includes pledges on immigration.

- Published21 August 2019

- Published28 February 2019