Migration data: Why is it so hard to count people?

- Published

The UK's Office for National Statistics (ONS) has downgraded the reliability of its own method for measuring migration, after discovering serious flaws in its methodology. So do we ever really know the scale of UK migration?

The headline migration figure is the number of people arriving in the UK who are planning to stay for at least a year, minus the people who are leaving the UK and planning to be away for at least a year.

The latest figures for net migration from the European Union, external estimate that in the year to the end of March, 59,000 more EU citizens came to the UK than left. That is the lowest figure since 2013.

But that number is not the full story. It's not a spot-on accurate count. As of this week, it is merely an "experimental" statistic after the ONS concluded it has been systematically underestimating EU migrants and overestimating others. That means it is no longer one of the 850 trusted "national statistics" that drive decisions across the nation every day.

This is of little surprise to experts who have repeatedly warned of shortcomings. In fact, the ONS itself has long said the core component of the system had been "stretched beyond its purpose".

How has it been counting migrants?

Every three months the ONS publishes a migration update. At the heart of this is the International Passenger Survey (IPS)., external

This enormous exercise was launched in 1961 to help the government understand the impact of travel and tourism on the economy - but over the years, it became, for political purposes, a proxy for finding out about who was coming and going, and estimating their long-term migration intentions.

For 362 days a year, cheerful IPS staff bounce in front of travellers at 19 airports, 10 ports and the Channel Tunnel rail link. Their short, voluntary questionnaire records a little bit of the travellers' life story: where they are from, why they are in the UK and how long they might be staying.

Just 800,000 people a year take part and the results are put through the statistical mixer to come up with an estimate for the number of people either arriving to live in the UK or leaving the UK for at least a year - the internationally-agreed definition of a long-term migrant.

But the IPS does not cover all the ports, all of the time. Take Dover, for example. There are up to 51 ferry arrivals a day - but the IPS activity at the port is equivalent to capturing about a week's worth of that traffic across an entire year. The total nationwide sample is roughly equivalent to 1% of Heathrow's annual traffic.

Within the sample, the number of known migrants is about 4,000. So they are an incredibly small group, within an already small sample, upon which statisticians are expected to give ministers some big answers.

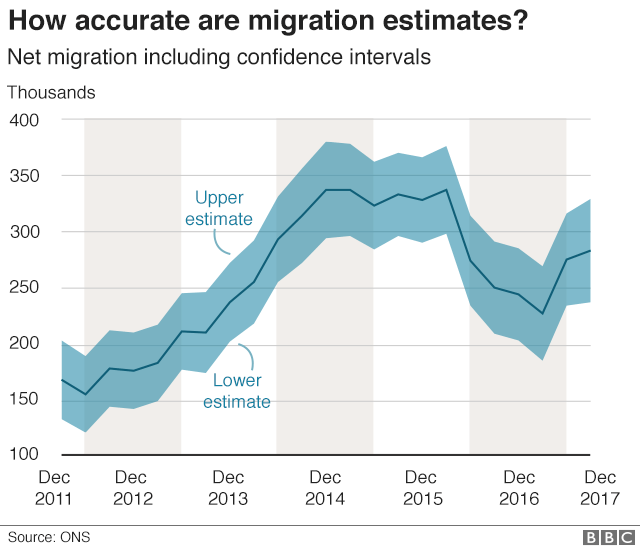

The ONS has never said the scheme is perfect. And to help explain the uncertainty it publishes figures that, in layman's terms, show how confident it is in the estimates.

Here is how it works. In July 2018, for example, the ONS estimated net migration to be 282,000 a year. But there was a large margin of error. The ONS is 95% confident that the actual figure is within 47,000 either way. So net migration may have been as low as 235,000 or as high as 329,000.

That is the statistical problem with surveys the world over. And two parliamentary committees in just over a year concluded that the IPS was next to useless, on its own, for what ministers expected it to do.

And those statistical uncertainties matter most when they are taken as facts by politicians and policy-makers.

Here is an example.

In 2015, a sizeable gap between the number of international students arriving and leaving prompted accusations that a lot of students were illegally overstaying their visas.

"The fact is too many [students] are not returning home as soon as their visas run out," Theresa May - then home secretary - told that year's Conservative Party conference. "I don't care what the university lobbyists say. The rules must be enforced. Students, yes; overstayers, no."

It turned out there was no mass overstaying. The first-ever experimental deep dive into departure gate data (more on that in a moment) revealed the vast majority of students went home on time. The gap was all down to the limitations in the IPS.

Those limitations led one parliamentary committee to later declare the statistics were so poor, external that ministries were "formulating policy in the dark".

Using new data

Major change is now under way.

In 2018, the ONS said it had begun to use other data sources, external in its migration estimates, including Home Office administrative data, such as records of granted visas.

It also used National Insurance numbers, which are a way of counting foreign nationals, but people do not cancel them when they leave the UK.

Home Office records of granted visas are great for counting people from most of the world, but you do not currently need a visa if you are an EU national or a returning Briton.

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) captures the nationality of people working in the UK. But it does not capture people in communal accommodation and does not cover short-term migration. And there have been claims that it has been undercounting migrants in specific sectors, such as hospitality.

Visa data can be used to measure migration, but not for EU citizens who have visa-free access to the UK

What about the UK census? It is the most definitive physical count of people we have - so reliable in fact, that the 2011 exercise added almost 350,000 to the net migration estimates for the previous decade.

But it is a mammoth undertaking, costing close to £500m. And it only happens once a decade, so it is not going to tell you much in an age of mass and rapid migration.

What do other nations do ?

A lot already have more sophisticated counts. No-one can enter or leave New Zealand until they have completed an entry or exit card. This system, which includes their own nationals, gives a pretty precise measure of who is where. The UK once had a similar system that was scrapped in 1998.

Italy is among the nations that has a rolling population register. People are supposed to register with the local authority when they move to a new town. The big problem with a register? People forget to register in the first place or forget to remove themselves if they move on.

Ways to measure migration:

Passenger survey: interviewing people at borders, but sample sizes mean there is uncertainty about the results. Used in the UK and Malta.

Visas: the number of people applying for visas to a country, but this does not count those with visa-free travel, such as citizens of the EU. Used in New Zealand, Australia, Canada.

Register: making all new migrants to an area register with a municipal hall. But some people do not do it or simply forget to say when they move on. Used in most EU countries.

Census: almost all countries do this, but it is expensive, so done at long intervals.

Denmark and Sweden try to resolve that problem by matching registers with other official sources, and it is this use of "administrative data" that is now seen as the holy grail of understanding migration.

The UK's long-delayed electronic replacement for exit and entry checks is now operational and the prize for statisticians is to take this data and mash it up with new sources, such as those already being used in those two Scandinavian countries.

The official plan in the UK is to come up with a "fully transformed" way of accurately counting people by 2023.

Denmark and Sweden are both seen as countries with better ways to capture migration

In an ideal world, statisticians would link the movement of real people to tax records and information about their whereabouts from other sources, such as registrations with schools and doctors' surgeries. The progress reports from the ONS say the initial experiments have been promising, but not without limitations.

Here is a good example. The ONS team ran an experiment to match workers' National Insurance numbers to information on the NHS's massive patient database, the theory being that the two sources taken together could give a more accurate measure of who was definitely in the UK.

But lots of EU-born workers could not be found in NHS records. There is a simple reason for this: we know that these workers tend to arrive young, childless and almost certainly reasonably healthy. On average, Polish workers take more than 500 days to first pop up in the NHS system, so you cannot rely on hospital databases to tell us a great deal about their presence.

So the ONS's aim is to use as many sources as possible. If the system can be made to work, the IPS would no longer be the primary source upon which so much policy is based.

- Published22 August 2019

- Published30 July 2018

- Published2 May 2018

- Published16 July 2018