Donald Trump, Hillary Clinton and the 'None of the Above' era in politics

- Published

As the world looks on askance at the freakishness of the US presidential election, it is worth bearing in mind that a large number of Americans feel much the same sense of unease.

To outside eyes, the rise of Donald Trump especially looks like the ultimate "Only in America" story, but many of his compatriots wish it was a "Not in America" phenomenon.

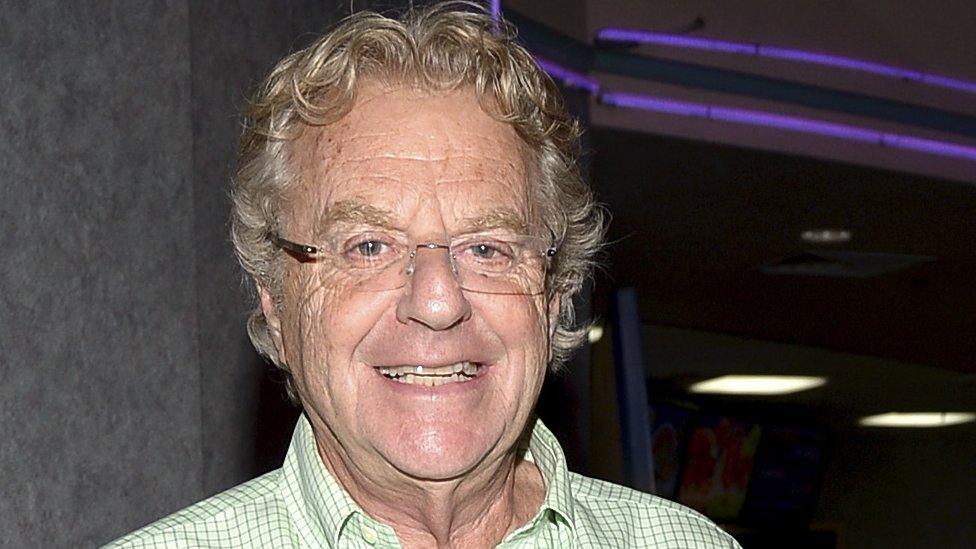

Just ask Jerry Springer, who recently told the Financial Times that the Republican race is too crazy even for his own show, a programme known for its on-stage punch-ups, pixelated nudity and madcap segments, such as "the man who married his horse".

For all the billionaire's dominance in the Republican race, for all the free airtime lavished upon him by the media, polls repeatedly suggest that he is the most unpopular presidential candidate in modern history.

A recent survey conducted for the Washington Post and ABC News, external showed that 67% of voters have an unfavourable view of him.

The Republican race has become too juvenile even for Jerry Springer

What's also striking about the polling data is that the more exposure the billionaire gets, the higher his negatives soar, whether it is women angered by his misogyny, Latinos upset by his racial demagoguery, African-Americans who don't take kindly to being called "the blacks" or fellow Republicans who believe he will lead their party off a cliff.

His hard-line stance on abortion - this week, before hastily backtracking, he said that women who opted for the procedure should be punished if abortion were made illegal - had the unusual effect of angering both pro-choicers and pro-lifers.

Though 7.8 million voters have backed Trump, often precisely because of his rollicking approach, more Republicans continue to vote against him than for him. In primaries and caucuses he's won 37.1% of the vote and never more than 50% in any one primary.

As the Harvard political scientist Danielle Allen recently pointed out, external, Trump claims to be the spokesman of America's "silent majority" but, like so many of his boasts, it does not withstand close scrutiny. Presently, he represents a minority. So far, Trump has won the votes of just 6% of the American electorate.

More on the Trump campaign

The 40-year hurt - How Bruce Springsteen articulated the forces that underpin the rise of Trump

Trumpisms - 22 things that Trump believes

A civil war - Lifelong Republicans turned off by Trump

Lesser of two evils

It would be wrong, however, to think that all the negativity and voter antipathy is directed against Trump.

Hillary Clinton also has a high unfavourable rating

Though Hillary Clinton is more popular than the property tycoon with general election voters, she still has the highest unfavourable rating - 53% - of any Democratic candidate in the past 30 years. To many, she fails the basic trust and likeability tests.

So with polls repeatedly suggesting that both Clinton and Trump are viewed unfavourably by a majority of Americans, with historically unprecedented negative ratings, America is heading towards a lesser of two evils style presidential election.

More on the Clinton campaign

Travels with Hillary - On the campaign bus with Clinton

Women problems - Clinton's struggle to appeal to female voters

Shouting row - Clinton's voice and tone under fire

The unpopularity of the front-runners is a reminder that we live in a "None of the Above" era of politics, in America and elsewhere.

Out of the five remaining candidates, only two, Bernie Sanders and John Kasich, have positive approval ratings, but neither is translating that relative popularity into getting enough votes to win at present.

Robotic careerists

Part of the reason for this none of the above dynamic is a rejection, globally, of the political class. Voters just don't seem to warm to careerist politicians who have devoted their working lives to politics, a self-perpetuating cadre who seem to be increasingly detached from the people they represent.

Their sound bites sound contrived, prefabricated and overly rehearsed. Their views often seem to be dictated by focus groups rather than conviction. Their primary goal, their overriding motivation, frequently seems to be accruing power, rather than using it to effect change.

Marco Rubio was mocked for his robotic delivery during his campaign

To many, figures like Hillary Clinton just seem too pre-programmed, too pragmatic and too overtly political. As the veteran commentator Jeff Greenfield wrote in Politico last month, external: "It's almost as if her brain and tongue were on a seven-second delay in which every word is subject to a pre-utterance examination for potential damage."

Marco Rubio suffered from the same affliction and never recovered from the charge that he was a robot, a political automaton.

Antipathy towards the political class explains the rise of protest candidates like Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders.

Self-styled anti-politicians - Sanders has successfully cast himself as an outsider, despite serving in Washington since 1991 - their unexpected success stems from their defiance of political convention and an authenticity, however idiosyncratic, that sets them apart from conventional politicians.

Shallow pool

Trump and Sanders have not just benefited from the repudiation of the political class, but also its qualitative weakness. In all the coverage devoted to Trump's rise, one key point often gets overlooked: his unexpected strength is due in part to the weakness of his Republican rivals.

The billionaire has risen to the top of a shallow Republican talent pool. The best that the GOP establishment could come up with - Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, Chris Christie and John Kasich - managed between them to win only three contests to date, in Minnesota and Puerto Rico (Rubio) and Ohio (Kasich).

The upshot is that many conservatives complain they are now being presented with a woeful choice, either Trump or his main rival Ted Cruz.

Senator Lindsey Graham, a failed candidate himself, described it as akin to choosing between being poisoned or shot, perhaps the most pungent description yet of the none of the above trend in politics.

Like Donald Trump in the US, Jeremy Corbyn has energised the Labour Party's base in the UK

This is not solely an American problem. Just cast your eye across the pond. In last year's Labour leadership contest, Jeremy Corbyn, another anti-politician, was the beneficiary of a weak and underperforming field of rivals, all of whom were career politicians.

Labour's political class failed to produce a strong enough candidate to beat him, just as the Republican political class has seemingly failed to produce a strong enough candidate to halt Trump.

However, as Trump and Corbyn demonstrate, there are limits to the appeal of protest candidates and anti-politicians. While both have, in wildly different ways, energised their bases, they have also struggled to appeal to general election voters.

Though Trump probably has a better chance of occupying the White House than Corbyn does of living in Downing Street, polls suggest that both are long shots and that voters will ultimately opt for more conventional politicians, albeit without any great enthusiasm.

Thus, the rise of anti-politicians has not done much to improve the political choice for voters, or alter the none of the above paradigm.

Notable absentees

There remain leaders in the political Anglosphere who voters not only seem to respect but also like and trust. Three examples are Nicola Sturgeon, Scotland's First Minister, Justin Trudeau, the new Canadian Prime Minister, and Malcolm Turnbull, Australia's Prime Minister.

But what's been noticeable in recent times is how many strong candidates choose not to seek high office - in the Labour leadership race, Alan Johnson and David Miliband were notable absentees - and how many best-in-their-generation figures steer clear of politics altogether, choosing instead to change the world through working in business, NGOs or tech start-ups.

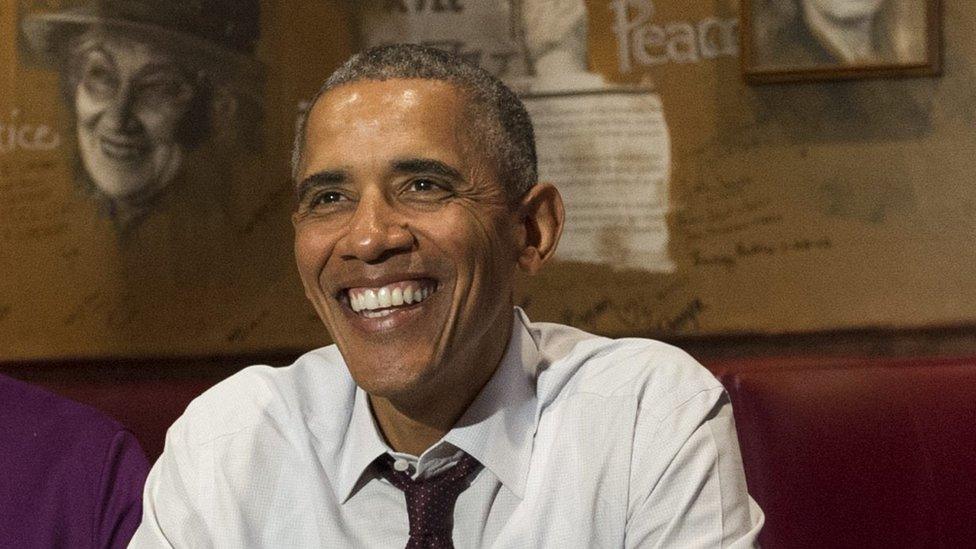

The current president's ratings have soared

One politician whose standing has risen in this election season is President Barack Obama. His approval rating is higher than at any time in the past three years.

But the most persuasive explanation for his surging popularity is the hostility towards his two possible successors and the sense of pre-emptive nostalgia that Campaign 2016 has brought on for presidency.

Still, it is worth remembering that President Obama's ratings are hardly stratospheric. His most recent approval rating - 53% - is a far cry from the 60-plus approval ratings that Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton enjoyed in the twilight of their presidencies, what now look like halcyon political days.

For whether products of the establishment or protest candidates pushed by anti-establishment insurgents, rarely have those running for high office been held in such low esteem. Politics may be broken, but anti-politics doesn't appear to offer a fix.