US election 2020: The 750,000 people you didn’t know could vote

- Published

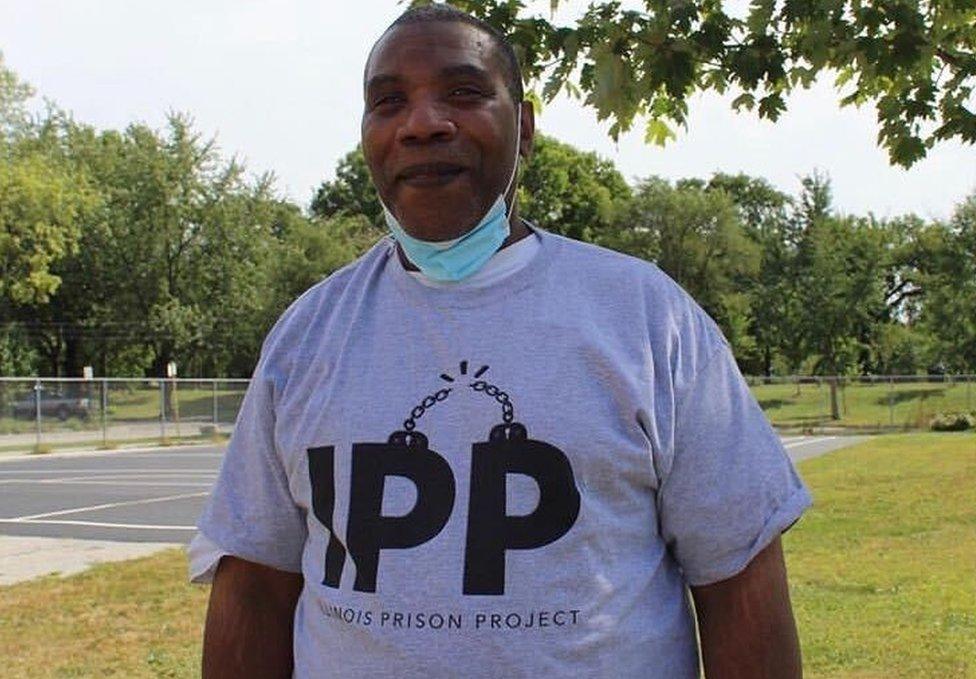

Renaldo Hudson spent almost four decades in prison, and now works with advocacy group Illinois Prison Project

Renaldo Hudson knew he needed to change his life when he got uninvited from a death row birthday party, for scaring the other inmates.

He laughs ruefully telling the story now.

Mr Hudson committed murder as an abused, drug-addicted teenager, and served 37 years in the Illinois justice system. He walked out a very different man, but considers he was fortunate to emerge at all. And having worked as a peer educator in prison, he's thought deeply about how to support incarcerated people and preserve their links to the outside world.

Now 56, he has a vocation for 2020: "I want to encourage a million people to vote!"

Why voting? Because it's a right that hundreds of thousands of people in jail don't know they have - and that unawareness locks them out of participating in democracy, and shaping their communities.

Mr Hudson is one of scores of activists pushing to prevent the mass disenfranchisement of up to 750,000 people in US jails.

The question of who can vote in the US comes down to the difference between prisons and jails. Prisoners, who have been convicted of felonies (more serious crimes) and are typically serving longer stretches, are barred from the ballot box except in Maine, Vermont and Washington DC.

But in jails, almost everyone is awaiting trial, or serving a short sentence for a misdemeanour. And in either case, they are entitled to vote.

It's worth stressing that most people in local jails haven't been convicted of a crime. They may be there purely because they can't afford $500 (£390) bail.

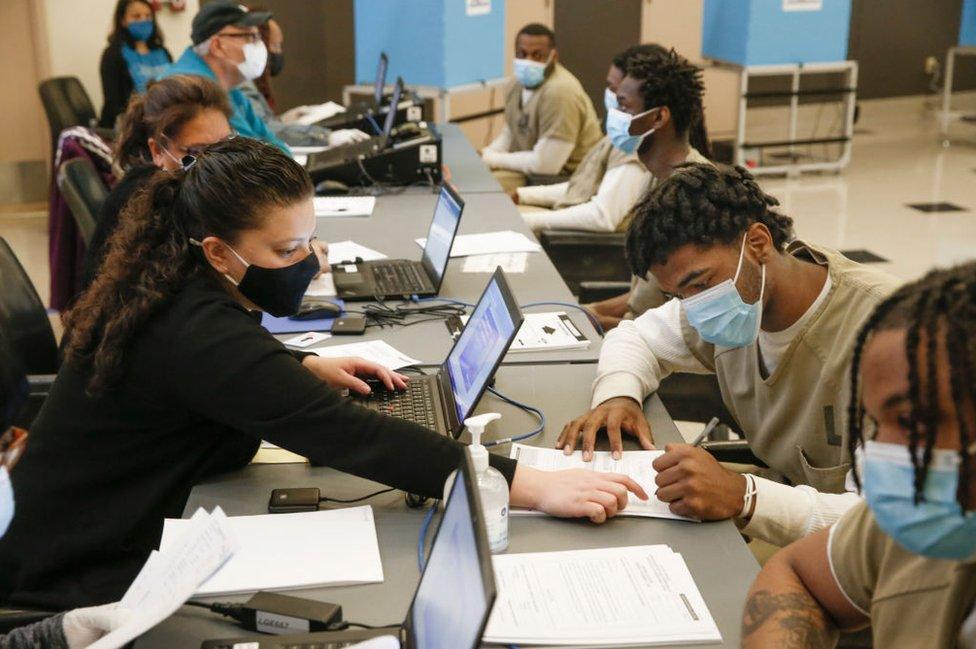

Chicago Votes registering people to vote at Cook County Jail, pre-Covid-19. This year, face-mask-wearing volunteers were allowed in for two days in September-October

In recent years, pro-democracy groups across America have sent volunteers into jails to educate, enthuse and register potential voters.

Some have still made it in this year - as in Harris County Jail in Houston, where a face-masked team registered more than 1,000 people in June at the sheriff's invitation.

Others have mobilised those inside, as in San Diego where Pillars of the Community, a criminal justice advocacy group led by black Muslims, paid detainees $17 an hour to help get out the vote.

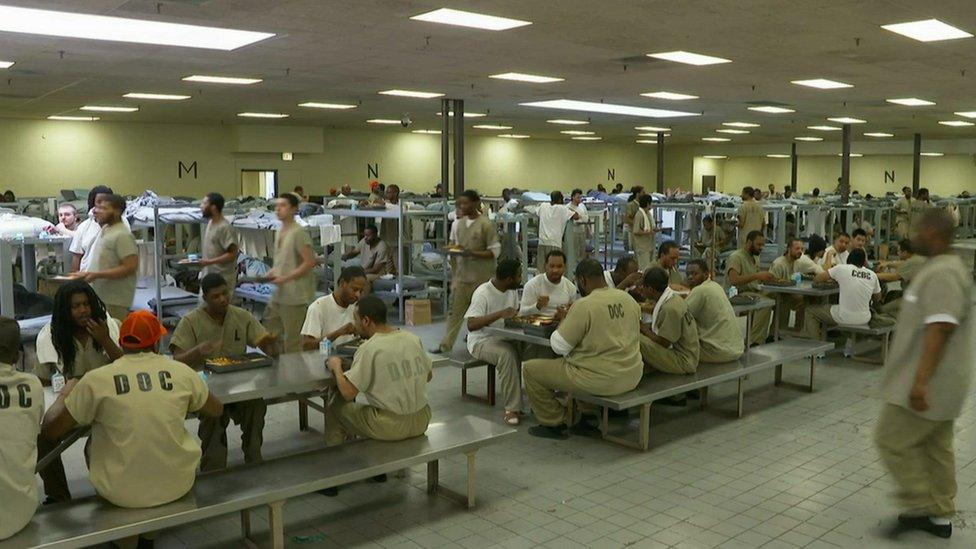

But generally the coronavirus pandemic has made in-person visiting significantly harder. Faced with overcrowding and a high population turnover, jails have suffered some of the country's worst outbreaks.

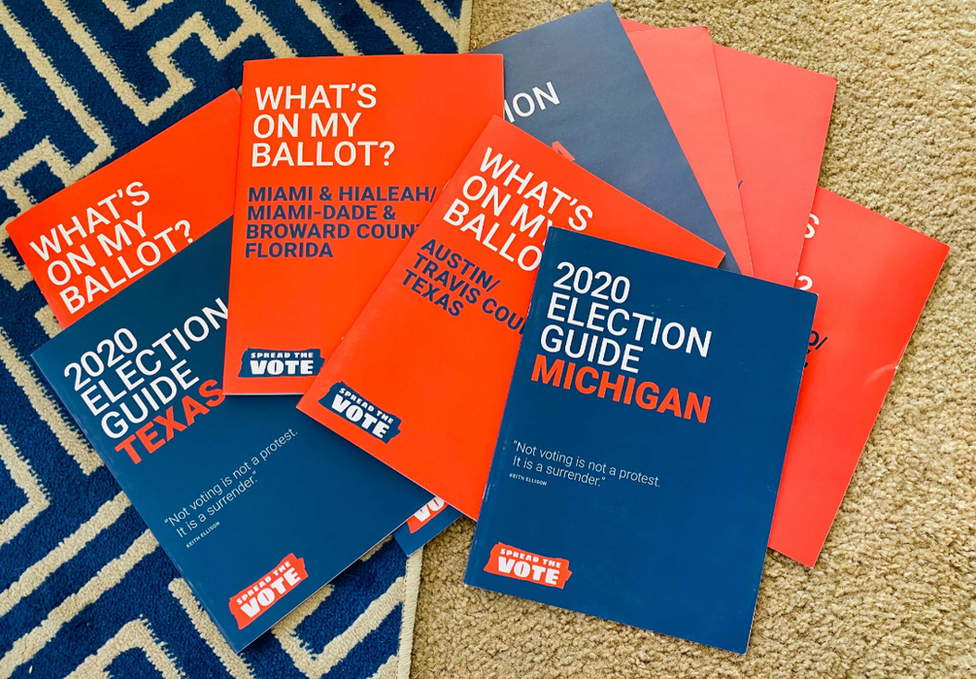

Kat Calvin, founder of advocacy group Spread The Vote, launched a programme called Vote By Mail in Jail, which is now in 52 jails across almost 20 states, to help bridge the gap.

"What we're doing is working through middlemen," she says. "From each of those jails we have a contact, which is either the jail administrator, or a chaplain, or it might be like a rabbi or someone who goes into the jail.

"So we train them to register voters and how to request absentee ballots. And then we have volunteers who write postcards to all of the incarcerated citizens in the jails saying 'hey, there is this programme, you can vote from jail, your in-house contact is Bob, go talk to Bob and he'll make it happen.'

"We know that it's working because one particular jail administrator called us very angry because too many inmates had approached them saying they wanted to vote.

"We were like, Yes! Let's make more people angry!"

Spread the Vote worked with jails in almost 20 states, training staff to register voters

Ms Calvin hopes the jails she works with will have finished their voting work before 3 November - the day of the US presidential election - thanks to absentee ballots which they are mailing in as fast as possible.

Voter rights advocates stress that mail-in voting from jail isn't as tidy an option as it might sound, however.

Jen Dean, deputy director of the non-profit group Chicago Votes, which works to increase ballot access, explains: "There's a lot of human error going through this process. Especially with absentee ballots that are in paper form.

"A person has to ask a guard to register to vote; the guard has to go and get a voter registration form; the person has to fill out the voter registration form; get it somehow back to the board of elections; fill out a ballot application form, then send that back to the board of elections. And then somehow find their ballot. All within jail, where you don't have access to money - you don't have access to pretty much anything. So that process, those seven steps, are a nightmare for somebody in jail."

Chicago Votes has a longstanding tie-up with the city's Cook County Jail, which holds roughly 5,000 people at any one time.

Its flagship programme has registered more than 5,000 voters since 2017. Then last year, civic advocacy groups successfully pushed through legislation making Cook County an official polling place, so people can vote there in person.

It's an outlier, as most state laws offer no protection for voters in jail. But on the third and fourth weekends in October, early voting went ahead - and the jail had its own voting machines, which Ms Dean considers essential.

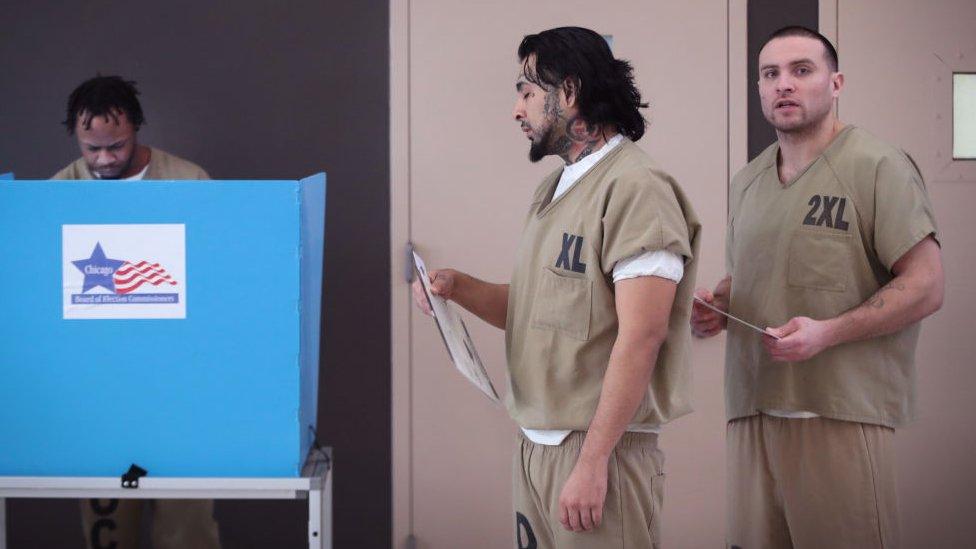

People in Cook County Jail check in before casting their votes early

"If you just have vote by mail, you will officially disqualify about 600 voters," she says. "Last election cycle we had around 1,700 voters, and 600 of them used same-day voter registration, which requires those polling machines inside the jail."

Sadly for those incarcerated, few jails liaise with local advocates the way Cook County's Sheriff Tom Dart has for years. There are logistical issues: Most states demand ID and a home address to register a voter. But jails generally confiscate drivers' licences when people arrive, and many people in jail don't have a fixed address.

Would-be voters may also be obstructed by hostile or ignorant officials and jail administrators - some of whom don't realise people in jail can vote.

On the other hand, it's true that some people will simply have no interest in voting - just as in the wider US population, where 61.4% said they voted in the 2016 presidential election.

Marc Mauer is a senior adviser at the Sentencing Project, a research and advocacy centre working for a fairer justice system. After decades in the field, he admits it's hard to get data on how many people in jail actually vote when they're given the choice.

"It seems like it's a relatively modest proportion, it may be as low as 10% or something like that," he says. "But nonetheless I think it's a question of democracy, you know - one person wants to do it, should they be able to do it? To my mind that's what we're looking at."

If the number of votes coming out of jail is low, that doesn't prove people don't care, or aren't trying. Jen Dean of Chicago Votes says she witnessed that before the voting machines arrived at Cook County.

"I was specifically in the women's division in the jail. Seventy-four per cent of the women in that jail said - I want to vote. And they all filled out the ballot applications. When it came time for their ballots, between people either getting out of jail, new people coming in, forms getting lost, incomplete forms, it comes down to only 20 to 40 ballots that actually get filled out. When there's 80-plus women in that division. So people definitely do want to vote, I think it's more the voting barriers that are placed in jail making it very difficult."

Simplifying the process can make a big difference to take-up. Since Cook County got voting machines, Mr Mauer notes, they had a "very high voter turnout in the [March 2020] primary". And for this election, it already stands at over 40% - which will rise as several hundred mail-in votes are added.

A team from Chicago Votes on a voter registration day (Centre, executive director Stevie Valles, Front-Right, deputy director Jen Dean)

Problems with voting in jail disproportionately affect communities of colour, because they are imprisoned at disproportionate rates. Almost half of those in US jails are African American or Latino.

Research shows that over-exposure to the criminal justice system (whether through police stops, arrests, or living in a heavily policed neighbourhood) makes people less likely to vote.

How do you make the case to someone uninterested or wary, who may never have cast a ballot before they were locked up?

Ms Dean says: "I would encourage people to think about the structures in their neighbourhoods or the environment that they grew up in, that may have led them down a pathway that ultimately led them to jail, or made it more likely for them to be incarcerated. These are systems that could have been structured in a way that could have helped you to avoid it, you know?

"The quality of the jails that they're in is horrendous, and unless those people that are actually impacted by the poor quality of the jail have a voice, they're going to continue to be ignored."

Another factor that can win over sceptical voters: In the US, elected officials such as sheriffs, judges and prosecutors are on the ballot.

"That is something that definitely resonates with people when they are going through the legal system," says Ms Dean. "Hey - did you know you either get to vote for this judge who helped you out, or you get to vote against this judge who you felt treated you unfairly?"

Voting gives people in jail a voice in their communities, advocates say

Prisoner turned community organiser Renaldo Hudson takes a more robust approach to voter recruitment.

"I'm doing a call-out every chance I get," he says. "How dare you walk around with the right to vote and you don't act upon it!"

This election will mark the second vote of his life and his first as a free man. The last time he cast a ballot was in the 1980s, when Chicago had its first black mayor, Harold Washington, and he was still in pre-trial detention.

He has this advice for people in jail who can vote, but might not:

"Listen, prison is already an inconvenience. Anyone that is incarcerated, or has been, knows that everything about prison is an inconvenience.

"Make the request. Because they don't have to like you, or the fact that you are making the request: it's your constitutional right. And it's your social duty."

Explaining the Electoral College and which voters will decide who wins

- Published2 November 2020

- Published6 November 2020

- Published5 October 2020

- Published27 July 2020

- Published20 October 2020

- Published6 October 2020

- Published20 May 2016