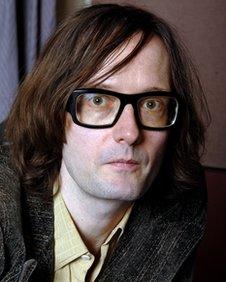

Jarvis Cocker: Pop poet

- Published

Pulp frontman Jarvis Cocker has been writing songs since he was 15 years old. Now, at 48, a selection of his lyrics have been collected in a book. But how did a geeky misfit from Sheffield become a poet for the Britpop generation?

Jarvis Cocker admits he is dangerously close to becoming a grumpy old man, so it comes as no surprise that he pines for a golden age of pop when, he says, music really mattered.

"Before, pop stars invented themselves," he says, contrasting the likes of Scott Walker and David Bowie with the manufactured stars of the X Factor generation.

He harks back to the days when kids waited eagerly for Top of the Pops every Thursday night and talked about it for days after. A time when teenagers identified themselves by the music they listened to.

"I don't know whether kids are using music in such a fundamental way any more," he says. "You can express yourself much more directly now by having a Facebook profile."

The singer's childhood and upbringing in Sheffield has had an overwhelming influence on Pulp's lyrics.

From the explicit scenes in Sheffield: Sex City to the fountain which plays a central role in Disco 2000, the city has coloured the band's music since they began performing there in 1978.

Pop and poetry: Listen to Jarvis Cocker on the BBC World Service

It started with a lunchtime gig at their comprehensive, The City School, where a young Pulp - then known as Arabacus Pulp - charged classmates 20p to see them play.

"We got a group together to play a show and I realised with horror that I had to write words," he recalls.

His first attempt was a song called Shakespeare Rock, which contained the lyrical gem: "Got a baby, only one thing's wrong. She quotes Shakespeare all day long. I said, 'baby why you ignoring me?'. She said, 'to be or not to be'."

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the song does not feature in his current anthology.

In fact, it wasn't until the mid-1990s that Pulp's blend of catchy melodies and Cocker's ability to capture the awkward, fumbling mundanity of life with irreverence and wit brought the band to fame.

"It took me a long time to take my eyes down from the lofty peak and realise that the stuff that was strewn around me was the stuff I had to be writing about," he says.

Pulp's full, original line-up played together for the first time since 1996 this summer

"We have dreams of what we want our life to be and we always fall short don't we? So instead of editing those bits out and pretending that that incident didn't happen why don't we just embrace it?"

At the same time he admits to romanticising the Sheffield of his childhood.

"It's much easier to have a relationship with someone once you've split up with them and you can turn them into this saint who never did anything wrong. So I created a Sheffield of the mind," he says.

"All these details that maybe I overlooked when I lived there, had a tang of nostalgia but also exoticism."

Reality has a way of undermining pop's romanticism, though. That "fountain down the road" was demolished in 1998. Anyone wanting to meet there in the year 2000 would have been sorely disappointed.

"That was very mean," says Cocker.

'Clunky and obvious'

On stage, Cocker cuts a distinctive figure, dressed in a jacket and tie, jerking his arms into familiar, angular poses, with his thick horn-rimmed glasses tied around his head with an elastic band.

"Short of saving up for some corrective surgery you have to deal with the cards you're dealt with," he says. "If you exaggerate it enough it'll actually turn into a fashion feature."

Anyone who attended Pulp's reunion shows this summer will know that the band's music is much more than just Cocker's words. There are catchy melodies, clever bass lines and enrapturing performances, as well as Cocker's unique voice.

So how does it translate to the page? Is there a danger that the lyrics could seem neutered?

"Yeah, but it's exciting. It's like walking around the house naked," he says. "The thing was to try and arrange the book so they would come across in some way... but you are getting half the picture, I suppose."

But he fundamentally disagrees with the idea that song lyrics are poetry and objects to the way some bands present their lyrics on record and CD sleeves.

The singer has also directed music videos and played a role in Fantastic Mr Fox

"Often the words are laid out [and] they're kind of typeset to resemble poetry. That's always rubbed me up the wrong way because it's just not poetry," he says.

"The rhymes in lyrics tend to be very clunky and kind of obvious but it works in songs. I love the fact that songs rhyme, that's one of the real joys of writing for me. When you find a good rhyme you congratulate yourself. If you could high five yourself you would do."

Still, he is proud that his work will stand on bookshelves alongside that of poets such as Philip Larkin and Seamus Heaney and impressed that the lyrics he wrote as a young man still resonate today.

"I'm not a person who would sit at home listening to his own music, but I found myself having listened to them because we were about to do some concerts and I wanted to remember what the words were," he says.

"I was pleased, because it's not a given that you spend your adolescence doing something that stands the test of time. It could have been absolute twaddle."

But now that he is in his middle age, and apparently taking a pause from song writing, is the well of creativity drying up?

"I think that's a horrible way to think of life, as material. You're playing at it then and I think that's rubbish. At the moment I'm doing the living bit and maybe I'll start commenting about it in a while," he says.

"I don't really like happy songs, and I'm going through a relatively happy time right now. I don't want to spoil it by commenting on it."

Mother, Brother, Lover: Selected Lyrics, by Jarvis Cocker, is published by Faber and is out now. Listen to Jarvis Cocker speaking to Sarfraz Manzoor on The Strand from the BBC World Service.

- Published12 October 2011

- Published27 May 2011