Arnold Bennett: The Edwardian David Bowie?

- Published

Arnold Bennett was once considered a national figure, whose death caused widespread mourning

Arnold Bennett is probably the most successful and famous British celebrity you've never heard of, unless you've tried the omelette that bears his name.

The dish was invented at London's Savoy Hotel, where this lover of the high life often stayed.

The JK Rowling of his day, his books sold in huge numbers, he was a figure of huge influence in politics and culture, a friend of the newspaper magnate Lord Beaverbrook, and declined a knighthood after notable service running the French propaganda department for the British government during World War I.

When Bennett lay dying from typhoid in his flat at Chiltern Court above Baker Street station in 1931, London's city authorities laid straw on the streets to dull the noise. It was testament to his status as a great national figure.

Not bad for a pawnbroker's son with a terrible stammer from the grimy Staffordshire potteries' town of Hanley who dreamed of escape.

And that story of social mobility is what makes it all the more remarkable that Bennett's place in literary history is currently so obscure, especially compared to his great friend HG Wells, with whom he shared a fascination for the technological innovations like the cinema and cars that were transforming early 20th-Century life.

Bennett came to London aged 21, originally to be a solicitor's clerk. But after winning a literary competition he never looked back and never stopped writing; up to half a million words a year.

First he wrote short stories for women's magazines, then novels and more: He wrote blockbuster film screenplays (Piccadilly 1929) and discussed working with a young Alfred Hitchcock.

He wrote smash hit plays that made him a theatre celebrity. He wrote self-help guides, such as How To Live On 24 Hours A Day (still in print today).

Bennett's most famous novel The Old Wives' Tale is about two sisters one of whom elopes to a scandalous life in France and the other who stays at home running the family draper's shop.

The shop, now empty, that inspired the book still stands in Burslem. It used to belong to Bennett's maternal family. And by coincidence Peter Coates, the millionaire chairman of Stoke City FC started his family's Bet365 business in that very shop.

Coates is one of a significant core of Bennett devotees who believe Bennett deserves rediscovery.

The Old Wives' Tale was made into a 1921 film starring American actress Florence Turner

They include novelists Margaret Drabble and Sathnam Sanghera, who transposed the story of The Old Wives' Tale to an Asian corner shop in the 1960s and 70s for his recent novel Marriage Material.

Ask a Bennett admirer like Coates or Sanghera how they first came to read him, and almost always they say it's because someone gave them a book and they were hooked by his great stories and characters.

So why did Britain stop reading Bennett in significant numbers?

Many of his books are short and very readable. One of his funniest novels The Card was made into a much loved film starring Alec Guinness, shot on location in the Potteries.

But that was in 1952. And it was the 70s and 80s when the last major TV serialisations of The Old Wives' Tale and the Clayhanger trilogy were made.

Some fans say he wrote too much, some of it very mediocre. But that still leaves a dozen great novels and collections of short stories.

Many believe the long-term decline was down to the critical trashing of his reputation by Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury set of modernist writers which continued after his death in 1931.

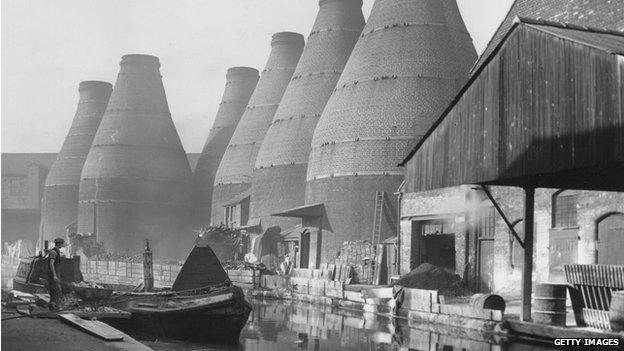

Arnold Bennett ruffled feathers in his native Potteries when in his novels he reduced the official number of towns included in the title from six to five and painted a gloomy picture of life there

Margaret Drabble, who wrote Bennett's biography, believes upper middle class snobbery at a lower class provincial writer was part of it.

But there is also the author's strained relationship with his roots. Bennett's most acclaimed novels were nearly all set in the Potteries that he'd been so desperate to leave.

He hardly ever went back. He turned the real six towns into a fictional five, which still rankles.

And in Clayhanger, Anna of the Five Towns and other books, the Potteries were portrayed as places of oppressive religious conformity, bullying Victorian patriarchs and philistine attitudes to art and literature.

This cryptic entry in Bennett's journal written on 20 October 1927 - nearly 40 years after he left - says it all: "I took the 1205 back to London, which went through the Potteries. The sight of this district gave me a shudder."

These days Stoke-on-Trent is proud of Bennett, but getting his books back onto school reading lists is a challenge.

You can still get an omelette Arnold Bennett at the Savoy Hotel or make one yourself, which is a lot cheaper. But why not try one of its namesake's classic novels instead?

Arnold of the Five Towns, written and presented by Samira Ahmed is on Radio 4 on Monday 23 June at 16:00 BST

- Published25 July 2013

- Published20 January 2012