Sir Andrew Motion's creation of verse from soldiers' words

- Published

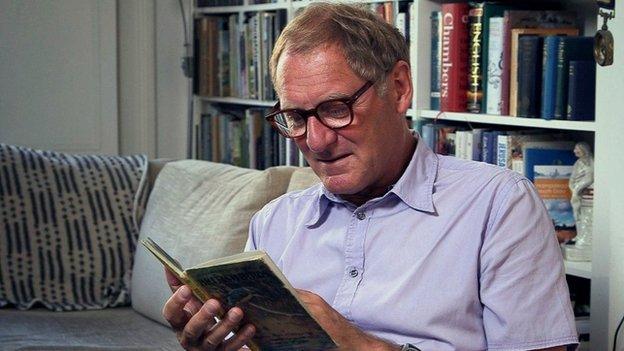

The first poetry book Sir Andrew Motion bought was by World War One poet Wilfred Owen

This year saw the end of the UK combat mission to Afghanistan. At its peak Britain had some 5,000 troops there. Now a small number remain in training and advisory roles.

The former poet laureate, Sir Andrew Motion, took the opportunity to discuss their experiences with British military personnel who had come back - and he's turned their words into poetry.

So far Andrew Motion's poems based on conversations with military personnel returning from Afghanistan have gone under the title Coming Home.

"But that's slightly misleading and maybe I'll change it when they appear in book form," he says.

The interviews were mainly recorded at the British military base at Bad Fallingbostel in Germany. "It's where the 7th Armoured Brigade, the Desert Rats, are based. But in a sense that's not really home for them either."

It's no coincidence that the poems have emerged when the centenary of World War One has meant the work of Wilfred Owen, Siegfried Sassoon and others has been much quoted.

"I yield to no one in my respect for that work," Sir Andrew says. "The first poetry book I ever bought was one by Wilfred Owen. But however great those poems are there's a sense that you're hearing the men speak through their officers and I wanted to do something more direct."

Dr Margaret Evison wrote a book about the death of her son Mark, a British army lieutenant

The interviews were set up through the MoD, "so it's true that the choice of men and women I spoke to was made for me - and most of the time there was a communications officer present," he adds.

"But the interviews were at length and at no point did I feel people were censoring themselves simply for fear of saying the wrong thing about their experiences in a political sense. So I wasn't fettered.

"But some of those experiences had been quite bad and I was aware that some kind of control was being exerted by the guys themselves. I think it's a mixture of not wanting to break the army code and not being willing to open up the Pandora's box of all the sights and experiences they recall from Afghanistan.

He soon realised his hopes of finding perfectly formed statements recalling intense experiences was unrealistic.

"The interviews were typed out and I suppose I hoped I would run my poetic water divining rod over them and it would tweak when I found something of real linguistic interest. But it didn't and for a time I thought that was a problem. But I recalled William Wordsworth's phrase about writing in 'the language such as men do use'. I thought here's a chance to follow that advice.

One Tourniquet by Andrew Motion

It was a long time ago

but I was there,

a combat medical technician.

I saw

children and IEDs

which wasn't nice at all.

One boy:

he had shorts and a dirty vest,

he stood on a mine;

he was conscious at first,

screaming,

and I thought

what a mess.

All in bit of field.

None of the other kids cried,

they're quite sort of tough.

Very tough kids in fact.

Definitely.

At the time

we were only issued one tourniquet each.

Camp Phoenix was down the road

and he went there.

A double amputee.

But we heard later he survived.

So yeah, brilliant.

Everything is hard.

Everything they've got to do,

everywhere they've got to go.

Just hard.

I used to imagine

little towns in the country

nobody knew.

Little towns nobody had touched.

There would be people living there

all the same.

Just living there

in the vastness.

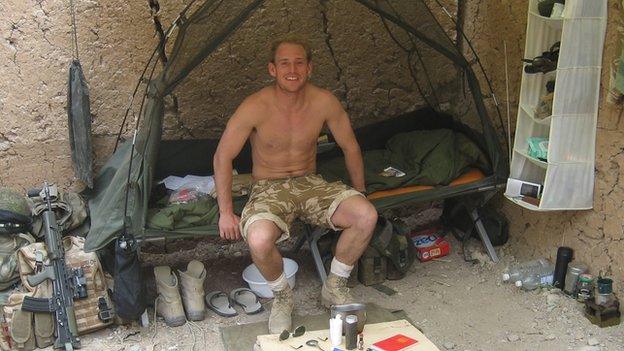

Sir Andrew recalls at first Sergeant Vicky Clarke was hesitant to discuss her time as ambulance crew and the specific incident which led to his poem One Tourniquet: "She'd had to deal with a young Afghan who trod on a mine and what she said wasn't in the usual sense poetic. But I hope that's what gives the piece its strength."

Sir Andrew says the thing almost all interviewees were eloquent about was the Afghan landscape. "It made me regret I was doing my interviews in Germany. Even people who found it hard to talk in personal terms about their own experience would talk in great detail about how gorgeous the countryside was.

"Perhaps it was a release mechanism - something they could talk about from their hearts when other things were bottled up inside. And the one interview I did with someone not in the military also came to focus on landscape, or at least on a garden."

The exception was clinical psychologist Dr Margaret Evison. She had already written a book - Death of a Soldier - about her son Lieutenant Mark Evison. He died in 2009, aged 26, after being shot at Haji Alem in southern Helmand.

The poet says when he met Dr Evison he thought her a remarkable person: "We became friends and it seemed to me, however blunt this sounds, that the death of a soldier was an inevitable part of the story."

Extract from The Gardener

In Memory of Lieutenant Mark Evison

We spent

many hours kneeling together in the garden

so many hours

Mark

he liked lending a hand

watching Gardener's World

building compost heaps

or the brick path with the cherry tree

that grows over it now the white cherry

where I thought I mustn't cry

I must behave

as if he's coming back

*

It was just after Easter

with everything in leaf

he is so sweet really

though worldly

before his time

I kissed him and said

See you

in six months and he turned round

he turned round and said

*

I opened the garden for the first time

the National Gardens Scheme

you know

what gardens are like in May

and this man was hovering

outside the front

as we walked down the side passage

he said

I'm a Major

I said

O my son he's in the army

sort of brightly.

Dr Evison says despite having written her own book about Mark's death, she was happy to take part in Sir Andrew's project.

"When soldiers come home they carry so much pain in their heads and their hearts about their lost colleagues. I did understand why it was important for Andrew to talk to the parent of someone who had been killed in Afghanistan," she says.

"I had had a close relationship with Mark's soldiers: we had wept many tears together in funny little pubs all around the UK. So I knew what it meant to them to have that loss remembered. I was delighted that Andrew used me talking about the garden in May because it was something Mark loved too.

Lieutenant Mark Evison lost his life in combat in 2009 at the age of 26

"When Mark died it felt like it was the only death, the only loss. But of course since then I've come to understand the loss of the 400-odd families around the UK who've lost someone in Afghanistan. And there are perhaps 20,000 families in Afghanistan who must feel the same because they lost someone too.

"It's always lovely to talk about deep thoughts and have them heard. My career is as a clinical psychologist and I'm aware that it's not something we do very often as human beings. But Andrew listens very intently to people's real thoughts. Even if what they're saying is buried beneath."

- Published10 August 2014