Is streaming good for music?

- Published

Early in June 2015, Apple Music became the latest in a succession of music services, including Spotify and Tidal, which allow music fans to stream music directly from the internet without actually owning it.

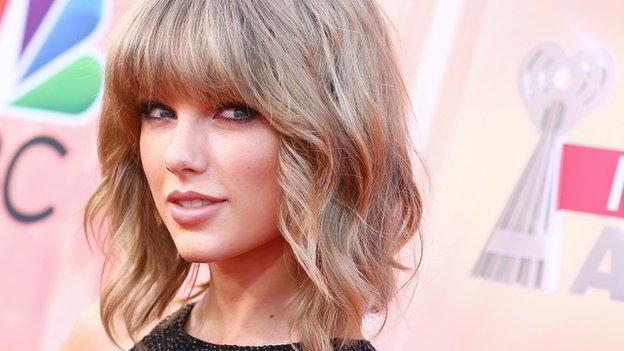

But days later Taylor Swift, the global popstar, published an open letter to Apple. She was shocked, she says, that during the three-month free trial for new subscribers, Apple would not be paying musicians for the songs its users streamed. "We don't ask you for free iPhones," she wrote. "So why should we give you free music?"

Apple quickly caved. But by then, the spat had reignited an important debate: does streaming reward artists fairly? There are other concerns too. Does it affect the quality and variety of music that's made? And does it change the way we listen?

In other words: is streaming good for music? Here, four experts give their views to the Inquiry programme.

Lucy Rose: It's getting harder to survive in the industry

Lucy Rose is a 26-year-old British singer-songwriter. She started by recording songs in her parents' living room.

"We put a video up and it was only from people sharing that YouTube video that actually anything happened with me. I was unsigned, playing small gigs, but that was a real big break for me."

After her videos and songs got millions of plays on streaming sites, a record company took her on, and began to promote her, even in countries where she didn't have a physical record out.

Lucy Rose

"We got flown out to do some shows in Singapore and Kuala Lumpur and China, and that was only possible because these streaming services were exposing my music to people that probably wouldn't have heard it otherwise.

"I feel like it's getting harder and harder to survive in the music industry and to get established in any way. Not as many people are buying records as they used to, which makes things a lot harder for us. Because if people don't buy my record... I will get dropped by my label."

"I was interested in the number of streams I got on Spotify and I think it was around five million plays of the entire album from start to finish, in America, which for me was really exciting. But at the same time I didn't see any money from that... so I don't think it's actually made a difference how the company sees me as an artist."

Spotify says that for five million individual plays, it pays $25,000. But they don't pay artists directly: instead they pay the artists' labels and publishers who own the music.

Chris Carey: A giant opportunity

Chris Carey works for Media Insight Consulting, a boutique consultancy focusing on data in the music industry.

"The reality for music streaming is you are changing the business model. You're going from paying for all your consumption upfront to almost paying as you go, so you get much smaller payments but you get them much more often. So rather than getting paid once for your album you instead get remunerated every time someone listens.

"There's a tightrope to be walked between valuing the artists appropriately for the work, but also then convincing consumers to pay.

"There's an argument that says the free service and the premium service are too similar. I think the challenge is to make the premium service even better rather than simply making the free service worse.

"The pricing would be different if we hadn't gone through the illegal downloading world but I think the fundamental challenge we've got is that music is undervalued as a result of that first step and what we're now doing is playing catch-up, that we're trying to compete with free.

"If you look at the decline of the recorded music industry, we are a small fraction of where we were 10, 15 years ago. We're now arguing about how we get out of that hole. For people who are innovating in that space, I'd be very happy to defend them.

"I think it's a giant opportunity if streaming can become a mass-market activity."

Carrie Colliton: I connect more with a record

Carrie is a music fan and vinyl obsessive who got her first job in a record store aged 20.

"I have streaming in my office and I can listen to music all day long and maybe not tell you the next day most of the artists I listen to. But if I'm purposely taking out a record that I own and putting it on, I'm choosing what that is and I'm connecting with it more.

Vinyl records still have their supporters

"I just really like the idea that I'm holding the physical artefact of what the musicians wanted you to have, what they created in their brain, you know. You can listen to it when you want and you can hold it.

"I was obsessive, like a lot of people, about reading the liner notes and learning about, oh, what does this person do, oh, this person was on the other album too, this other band, they must know each other.

"I think streaming has turned out to be, and will continue to be, an incredibly effective discovery tool. The fact that you can think of a song or read about an artist and you can go and listen to the music and have this giant listening station at your discretion is fantastic."

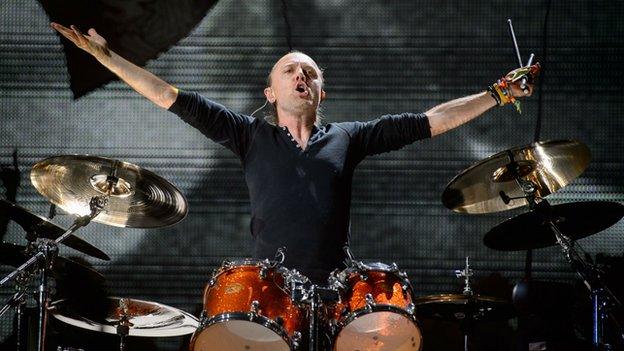

Lars Ulrich: Record companies take fewer chances

Lars Ulrich is the drummer with Metallica, the heavy metal band that's sold more than 100 million records.

"I believe streaming is good for music. I mean the thing that I read a lot is that people sit there and go, 'I'm not getting paid very much for streaming.' But there's one major thing that gets overlooked in that argument and the whole thing is that streaming is a choice on all fronts.

"It's a choice for the fan to be part of, it's a choice for the artists who are involved in making their music available on streaming services. It's a choice by the record companies that represent the artist. Fifteen years ago those choices didn't exist.

"Streaming probably does benefit artists with higher profiles. And if you listen to the playlists a lot of these playlists that are being made available for people in the streaming service, they seem to feature higher profile artists and that just seems to be the way it's sort of playing out right now.

Lars Ulrich

"One of the main reasons I connect less with new music in my life now is because there's less great new music to connect with. A lot of the stuff that's been played is just regurgitated, this year's flavour, this thing, but it's not people on the leading edge like the Beatles or the Miles Davises or the Jimi Hendrixes taking us all by the hand into these completely unknown, uncharted musical territories.

"When there's less people buying music, there's less money generated back and record companies take less chances and instead of promoting 500 records a year, they promote 50 records a year and they don't put the same amount of money into breaking new art. The saddest thing about all of this is that there's less and less money being put into younger artists and there is a danger of younger artists coming close to extinction.

"Thirty, 40 years ago I would get on my bike, drive to the record store, spend time figuring out which record I could buy by listening to a bunch of them. By the time I got home I would end up spending every minute of my free time for the next week just acting with this particular record.

"Nowadays music, to an extent, for some people it's become kind of background noise."

The Inquiry is broadcast on the BBC World Service on Tuesdays from 12:05 GMT/13:05 BST. Listen online or download the podcast.

- Published30 June 2015

- Published23 June 2015