The emotions that make a film a hit... or a miss

- Published

- comments

On the surface, The Godfather, The Sixth Sense and Little Miss Sunshine appear to have little in common.

But even though these films belong to different genres and have very different plots, technically they have the same "emotional arc" - a journey of highs and lows.

Using artificial intelligence, we analysed more than 6,000 scripts from the past 80 years and discovered all films fall within six emotional arcs.

These include the emotional rise of "rags to riches" films such as The Shawshank Redemption and the rise and fall of "man in a hole" films such as Who Framed Roger Rabbit.

But which of these are the most successful, critically and commercially?

Tragedies, which depict a continuing emotional fall, appear to receive the highest number of Oscar nominations per film.

This new technology means scientists may be able to give the film industry the tools to understand their viewers and work out what they really want to see on screen.

Critical acclaim

The tragedies we studied won an average of 2.14 Oscars per film.

For example, political thriller The Constant Gardener was nominated for four Oscars, winning the best supporting actress award for Rachel Weisz, in 2006.

Telling the story of a British diplomat in Kenya uncovering the mystery behind his wife's death, it follows a downward emotional arc.

But while they may be critically acclaimed, these "riches to rags" films often fail to set the box office alight.

Angelina Jolie (right) won an Oscar for Girl, Interrupted

Consider Lawrence of Arabia, one of the most critically acclaimed films of all time, which received seven Oscars in 1963, including the best picture award. It initially flopped at the box office, making close to $6m (£4.7m) compared with a budget of $15m, external (£11.8m).

Another example is Girl, Interrupted which earned Angelia Jolie the best supporting actress win in 2000 but failed to achieve box office returns, external.

When it comes to financial success, it is actually "man in a hole" films - an emotional fall followed by a rise - that come out on top, regardless of genre or production budget.

How it works

Using a filtering process, external, we selected 6,147 films released between 1935 and 2018 and added up Oscar nominations in all categories.

Our machine learning algorithm then split each film script into sentences.

Each sentence was given a score calculated by averaging the sentimental value of each word. An emotionally negative term scored minus one, an emotionally neutral term scored nought, and an emotionally positive term scored one point.

Toy Story 3 is an example of a "riches to rags" emotional journey

The total sentiment for each film was accumulated and overlaid on to the span of the film, to map the emotional arc.

Films were then grouped based on the similarity of their emotional arc. By doing this, scientists discovered that films, like novels, all fitted within six standard emotional journeys, external:

Rags to riches: a continuing emotional rise (eg The Shawshank Redemption, Groundhog Day, The Nightmare Before Christmas)

Riches to rags: a continuing emotional fall (eg Psycho, Monty Python and the Holy Grail, Toy Story 3)

Man in a hole: a fall followed by a rise (eg The Godfather, The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, The Sixth Sense)

Icarus: A rise followed by a fall (eg On the Waterfront, Mary Poppins, A Very Long Engagement)

Cinderella: "rise-fall-rise" (eg Rushmore, Babe, Spider-Man 2)

Oedipus: "fall-rise-fall" (All About My Mother, As Good as It Gets, The Little Mermaid)

Following the money

If man in a hole films are the most profitable, should the entertainment industry just make those?

The answer is probably not, for several reasons.

While those films do make the most money, we discovered that the right combination of genre and budget can produce a financially successful movie of any emotional shape.

Lord of the Rings: Fellowship of the Ring is an example of the financially successful "man in a hole" structure

For example, the "Icarus" arc - a rise followed by a fall - is good for low budget films, such as 2005's family drama Junebug.

However, if you want to shoot a financially successful tragedy, then it helps if it is epic, with a large budget of over $100m (£78m).

Sad superheroes

Superhero films are a perfect example of this.

In this genre, man in a hole films become only the second most profitable after epic tragedies, ie riches to rags films with plenty of funding.

However, superhero tragedies seem to attract bigger than average budgets anyway - $186m (£147m) - and bring in an average revenue of $310.5m (£245m).

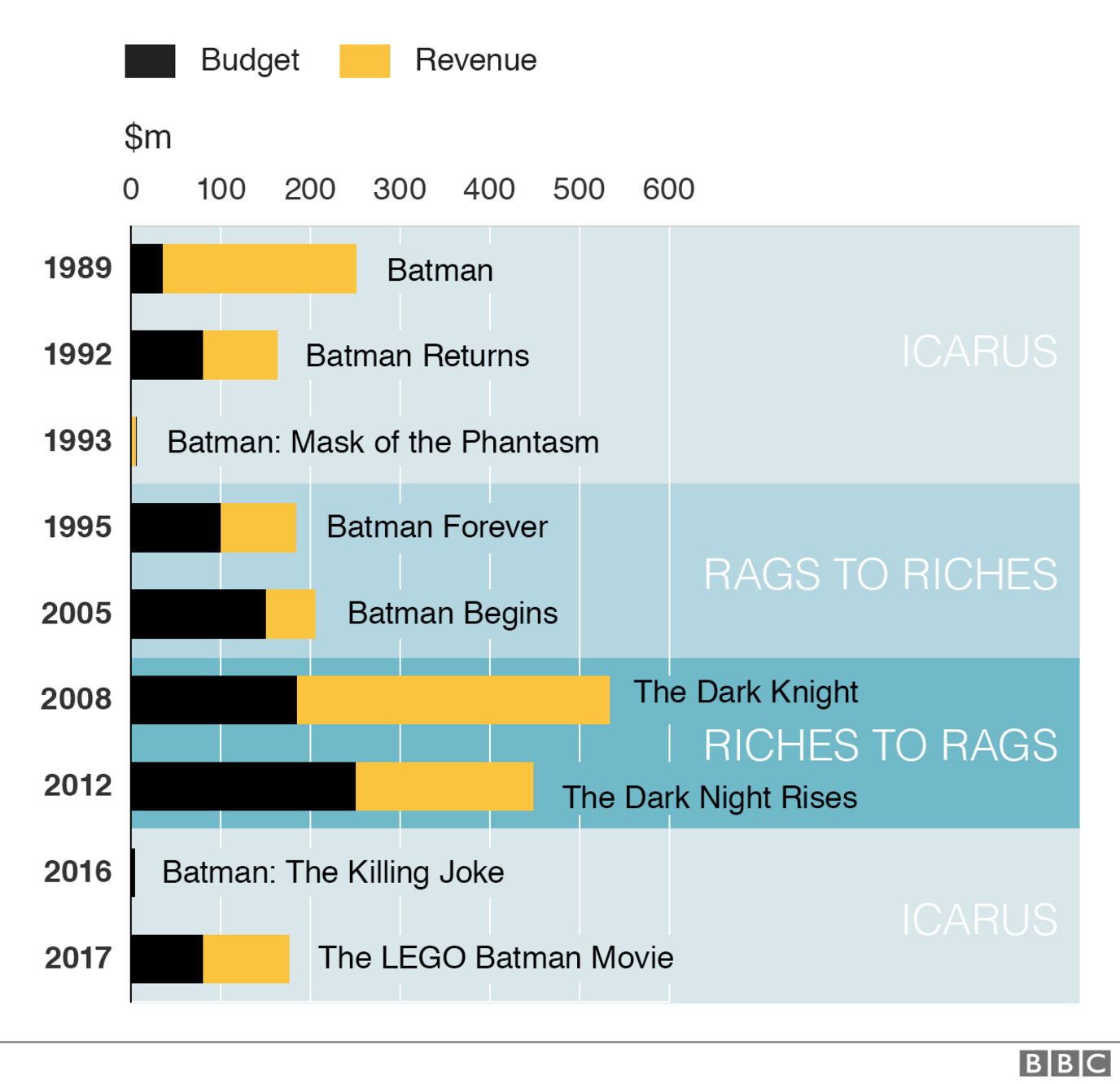

Looking at all the mainstream Batman films, you can see the top performers were the epic tragedies - the Dark Knight films.

Sci-fi, mysteries, and thrillers with happy endings - the rags to riches shape - do not tend to do well at the box office.

This includes the Wachowskis' sci-fi epic Cloud Atlas, which flopped at the box office in 2012, making $27m, external (£21.3m) in the US against a budget of about $128.5m (£101.5m)

Equally, it is not a good idea to shoot a comedy with a sad ending.

Tom Hanks and Halle Berry starred in sci-fi epic Cloud Atlas, which had a budget of about $128.5m (£101.5m)

Writing by robot

The entertainment industry tends to make ad hoc, top-down decisions about the content offered to the viewer.

Determining which films get the green light is based primarily on the intuition, expertise and experience of a relatively small group of producers and studio executives, with limited input from focus groups.

Could machines do better?

Recently, a bot was "employed" to produce a sci-fi film, external, with nonsensical and sometimes hilarious results, highlighting how far automated scriptwriting still has to go.

That's because robots still aren't very good at replicating the nuances of human emotion, especially humour, and struggle to write scripts to which people can relate.

But we can use data science to enhance the efforts of human scriptwriters and production companies.

Time will tell whether these new techniques will actually shift decision-making about film content from producers to the viewers.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Ganna Pogrebna, external is a fellow at The Alan Turing Institute, the UK's national centre for data science and artificial intelligence.

She is also a professor of behavioural science at the University of Birmingham.

Edited by Eleanor Lawrie