The places where too many are fat and too many are thin

- Published

Obesity is often portrayed as a Western problem, with under-nutrition found in poorer countries.

But the truth is more complex. Nine out of 10 countries are in the grip of a health epidemic known as the "double burden", external - where overweight and undernourished people live side-by-side.

A worldwide explosion in the availability of unhealthy foods, a shift towards office jobs and the growth of transport and television are among the many causes.

Often, this double burden occurs not only within a community, but also within the same family.

It can even happen within the same person, who is overweight but lacking in vital nutrients. Alternatively, they can be part of a phenomenon known as "thin-fat", where people appear to be a healthy weight, but carry large amounts of hidden fat.

Obese children

Every country in the world is struggling with a nutrition problem of some kind.

The number of people suffering from chronic food deprivation reached an estimated 815m in 2016, external - a 5% increase in two years. Much of the increase was in Africa, where 20% of people were malnourished.

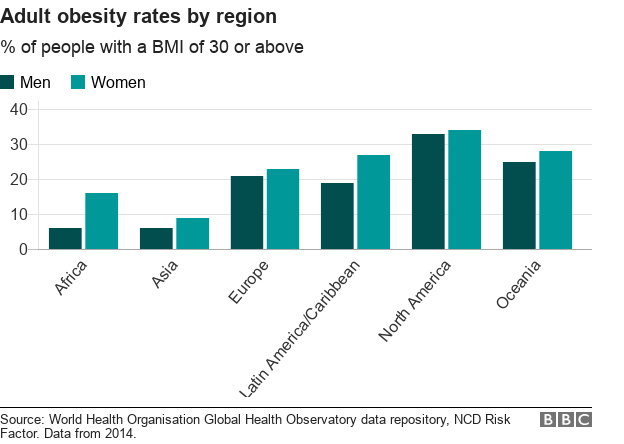

Meanwhile, obesity rates have tripled, external over the last 40 years. Globally, more than 600m adults are obese, while 1.9bn are overweight.

The number of obese people in developing countries is catching up with the developed world.

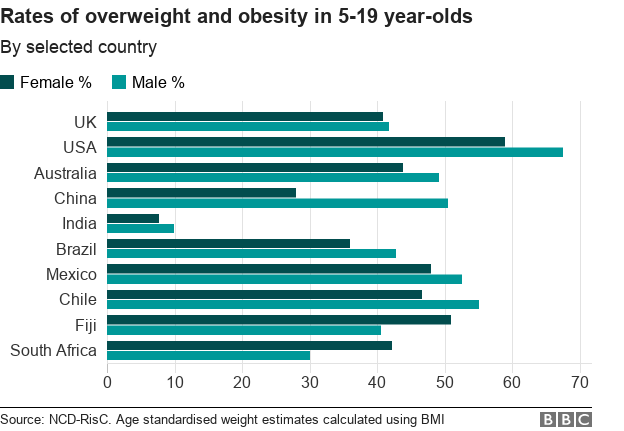

The highest rates of childhood obesity can be found in Micronesia, the Middle East and the Caribbean. And since 2000 the number of obese children in Africa has doubled.

In many places it is common to find children whose diet does not meet their needs.

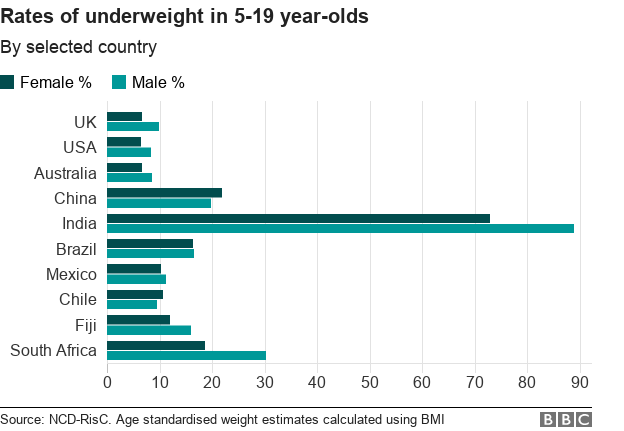

In South Africa, almost one in three boys are overweight or obese, external, while a further third are underweight.

In Brazil, 36% of girls are overweight or obese, while 16% are classed as underweight.

Money to spend

Lifestyle changes are partly to blame for the double burden of obesity and under-nourishment.

Many low and middle-income countries, such as India and Brazil, have a new middle class with disposable income, rather than just the money to spend on essentials.

Often, this has meant a move away from traditional foods towards more Western diets high in sugars, fats and meat, and low in unrefined grains and beans.

In some countries this has also happened as people move from the countryside to the city, where there is much more choice of food.

For example, a study of young children in China, external suggested that in the countryside, obesity rates were 10%, while the malnutrition rate was 21%. In cities, 17% of children were obese while 14% were malnourished.

Obese students at a weight loss summer camp in Zhengzhou, China

Although many people's diets may be higher in calories, they can still offer too few vitamins and minerals.

Professor Ranjan Yajnik, a diabetes specialist in Pune, India, is seeing first-hand one impact this change of diets is having.

"Diabetes was considered a disease of the older and more obese," he says. "But in India we're seeing it in younger people and with a lower BMI."

Indians are eating fewer nutrient-rich foods and getting more calories from junk food, he says, resulting in the problem of thin-fat - "people who are thin by most criteria are actually carrying large amounts of hidden fat".

Hidden, or visceral fat, accumulates around internal organs, including the liver. High levels of visceral fat may increase the risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease, even if the carrier doesn't look overweight.

Tackling hunger

Children are particularly vulnerable to unhealthy diets, as they need vitamins and minerals in order to grow and develop normally.

Some households contain children who are undernourished, even as they eat the same diet as their obese parents, because they are deficient in vitamins.

Research also suggests stunted or malnourished children are more likely to become overweight later in life, external, as their metabolism slows and their body hangs on to fat reserves.

This means countries need to be careful that policies aimed at tackling hunger do not accidentally add to the problem of over-nutrition.

In Chile during the 1920s, a national programme was introduced to provide rations to pregnant women and the under-sixes.

This reduced hunger but in the long-term is thought to have contributed to Chile's rapidly rising rates of childhood obesity.

The West

While the double burden may be particularly prevalent in developing countries, the problem is also found in richer nations.

In the UK, for example, more than a quarter of adults are obese, costing the NHS an estimated £5.1bn each year.

At the same time, 3.7m children live in households which cannot afford to follow healthy dietary guidelines, with one in 10 living with severe food insecurity, external.

In the European Union, 14% of 15-19 year-olds are underweight, external, and a similar proportion are overweight or obese. However, more than half of over-18s, external are overweight or obese, while just 2% are underweight.

Choices

The causes of this double burden are complicated.

It is not only a question of having access to healthy foods, and no two people or cultures view nutrition in the same way.

Our food choices are influenced by many things, some of which we may not be aware of.

They include cost, local availability, time pressures, healthily eating knowledge and the diets of people around us.

And every person's nutritional needs are different. This partly depends upon their metabolism and how good their health was to start off with.

The cost to the individual and society of over and under-nutrition are numerous.

Children who grow up undernourished often do worse in school and earn less throughout their life.

Childhood obesity is likely to lead to poorer health in adulthood, and increases the risk of diseases like cancer later on.

Malnutrition is a particular risk for older people - making them twice as likely to visit their doctor and at risk of longer hospital stays.

Making progress

In developing countries, problems like diabetes and heart disease are likely to soar in tandem with obesity rates.

For health systems which have traditionally focused on infectious diseases such as malaria and have small budgets, this will be a huge challenge.

What can be done? South America - where many countries suffer from the double burden - is leading the way.

Brazil was the first country to sign up to the UN's Decade of Action on Nutrition, making many commitments, external. These include halting the growth in obesity, cutting consumption of sugary drinks by 30% and increasing fruit and vegetable intake by 18%. It aims to achieve these with policies such as microloans to farmers, reducing tax on certain fresh foods and educating children on nutrition.

Mexico was the first country to implement a 'sugar tax', imposing a 10% levy on artificially sweetened drinks in 2014.

This tax is predicted to reduce obesity rates by 12.5% in 12 years, external, and other countries such as the UK are now adopting similar measures.

But much more is needed in order to halt this global nutrition crisis.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Dr Sophie Hawkesworth works in the population health team at Wellcome and Dr Lindsay Keir is in Wellcome's Clinical and Physiological Sciences Department. They spoke at the October Wellcome/WHO conference "Transforming Nutrition Science for Better Health", external with the aim of generating new ideas and collaborations in global nutrition research.

Edited by Eleanor Lawrie