The violent solar storms that threaten Earth

- Published

A violent storm on the Sun could cripple communications on Earth and cause huge economic damage, scientists have warned. Why are solar storms such a threat?

In 1972, dozens of sea mines off the coast of Vietnam mysteriously exploded.

It was recently confirmed the cause was solar storms, which can significantly disrupt the Earth's magnetic field.

Today, the effects of a similar event could be much more serious - disrupting the technology we rely on for everything from satellites to power grids. The cost to the UK economy alone of an unexpected event has been estimated at £16bn, external.

There are good reasons why we are vulnerable to events taking place millions of miles from Earth.

What causes an extreme solar event?

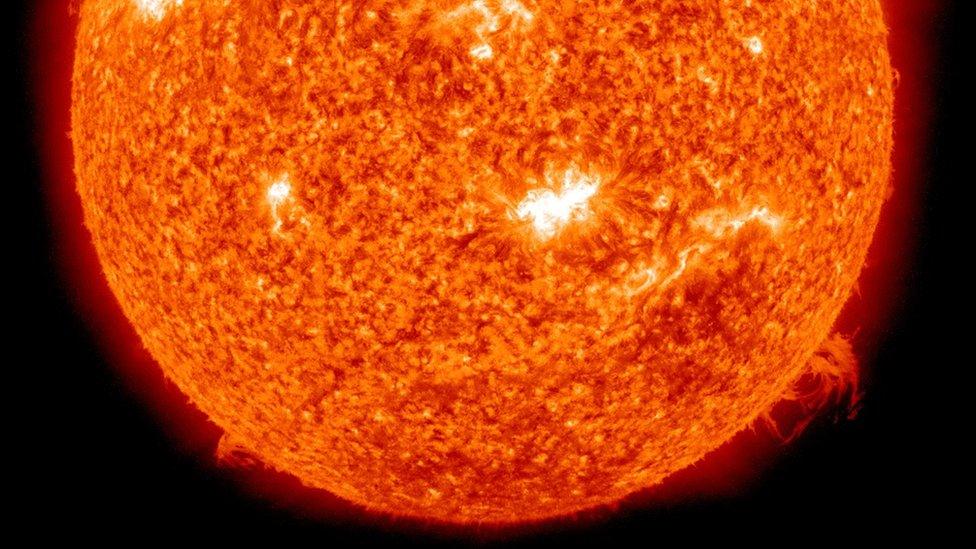

The Sun is a star, a seething mass of electrified hydrogen. As this fluid moves around, it builds up energy within its complex magnetic field.

This magnetic energy is released through intense flashes of light known as solar flares and through vast eruptions of material and magnetic fields known as coronal mass ejections or solar storms.

While flares can disrupt radio communication on Earth, solar storms pose the greatest threat.

Each storm contains the energy equivalent to 100,000 times the world's entire nuclear arsenal, although this is spread throughout an enormous volume in space.

The northern lights over Finland

The Sun rotates like a vast spinning firework, launching eruptions into space in all directions.

If one of these heads towards our planet, with a magnetic field aligned opposite to the Earth's, the two fields can merge together. As the solar storm washes past, some of the Earth's magnetic field is distorted into a long tail.

And when this distorted magnetic field eventually snaps back, it accelerates electrified particles towards the Earth. Here, they strike the upper atmosphere, heating it and causing it to glow in a spectacular display known as the northern and southern lights.

But this distortion of the Earth's magnetic field has other, more significant effects.

It is thought to have triggered the sea mines back in 1972. The mines were designed to detect small variations in the magnetic field caused by the approach of metal-hulled boats. But their engineers hadn't anticipated that solar activity could have the same effect.

When will the next extreme weather event happen?

Scientists are looking for clues as to what triggers these vast eruptions and, once they have been launched, how to track them through interplanetary space.

Our records of the Earth's magnetic field go back as far as the mid-19th Century. They suggest an extreme space weather event is likely to occur once every 100 years, although smaller events will happen more frequently. In 1859, the Carrington Event - most extreme solar storm recorded to date - caused telegraph systems to spark and for the northern lights to be spotted as far south as the Bahamas.

The next time it happens, the effects are likely to be far more serious.

Observers at the launch of a satellite

With every solar cycle, our global community has become more reliant on technology.

In 2018, space satellites are central to global communication and navigation, while aeroplanes connect continents and extensive power grids crisscross the world.

All of these could be badly affected by the aftermath of extreme solar events.

Electronic systems on spacecraft and aeroplanes could be harmed as their miniaturised electronics are zapped by energetic particles accelerated into our atmosphere, while power networks on the ground can be overwhelmed by excess electrical currents.

Planning ahead

Enough satellites and power grids have failed during past space weather events to make it clear that the Sun must be closely monitored, to help predict when a solar storm will affect Earth.

Forecasters are working on this all over the world, from the UK's Met Office to the Australian Met Bureau and the Noaa Space Weather Prediction Center in the US.

All being well, they can detect when a storm is heading towards Earth and predict its arrival time within six hours. That still leaves relatively little time to prepare but forecasting would cut the cost to the UK economy from £16bn to £3bn.

The Mauna Kea Observatory summit, in Hawaii

Space weather now appears on the UK government's risk register, external, alongside other, more familiar risks such as a flu pandemic and severe flooding. It has been rated at the equivalent risk as a severe heatwave or the emergence of a new infectious disease.

Government agencies are now speaking to power companies, spacecraft and airline operators to ensure they have plans in place to limit the impact of an extreme space weather event.

It is vital, for example, to make sure enough power is available to refrigerate supplies of food and medicine as well as to make sure water and fuel can be pumped as needed.

If communication with some satellites is lost, familiar technologies such as sat-navs and satellite television could stop working.

Spacecraft engineers study extreme events so they can build resilience into spacecraft, protecting vulnerable electronics and installing backup systems.

An accurate space weather forecast would enable operators to further protect their assets by ensuring they were in a safe state as the storm passed.

Many planes fly over the north pole en route from Europe to North America. During space weather events, aircraft operators re-route aeroplanes away from the polar skies, where most of the energetic particles enter Earth's atmosphere.

This is to limit exposure to enhanced radiation doses and ensure reliable radio communication.

We have learned much about space weather since the events of 1972 but as modern technologies evolve, we need to make sure they can withstand the worst the Sun can throw at us.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Chris Scott, external is a professor of space and atmospheric physics, at the University of Reading. Follow him on Twitter at @ProfChrisScott, external.

Edited by Eleanor Lawrie