White Crow's star dancer 'channelled' Rudolf Nureyev

- Published

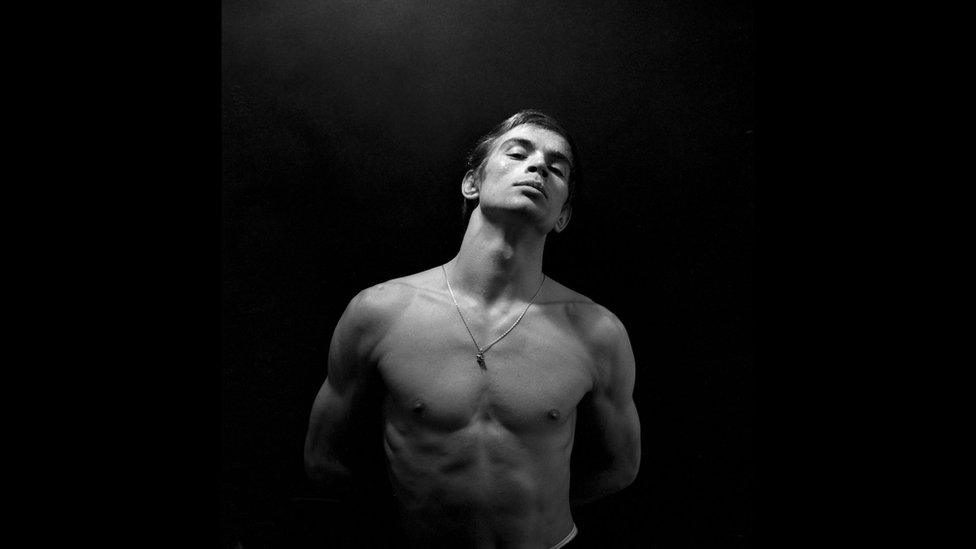

Dancer Oleg Ivenko, who stars as Rudolf Nureyev in The White Crow, had no previous acting experience

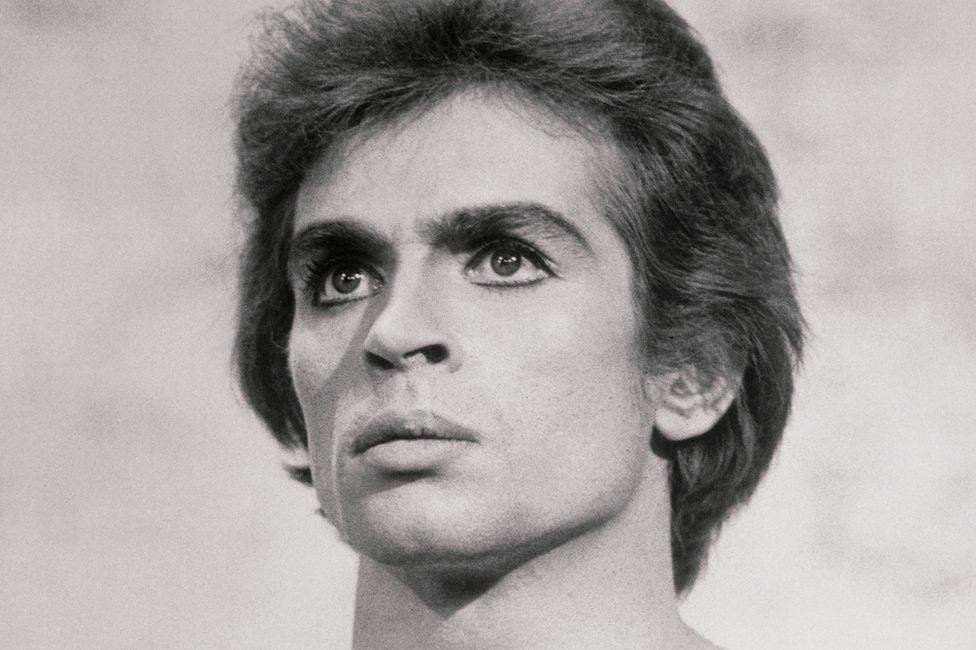

In 1961, the dancer Rudolf Nureyev defected to the west from the then-Soviet Union's famed Kirov Ballet. An apparently last-minute decision to seek asylum in France made him, at 23, the best known male dancer in the world. A glittering career followed. The new film The White Crow dramatises the defection and the early years which led to it.

When Nureyev outwitted his KGB minders at Le Bourget airport (then the main airport for Paris), he became famous overnight. A propaganda coup had fallen into the lap of the west in its Cold War with the Soviet Union. Nureyev became that rare thing - a male ballet dancer whose name was known worldwide. He spent the next 30 years delighting in his celebrity.

At 22, the dancer Oleg Ivenko hasn't acted before but he was chosen by director Ralph Fiennes to play Nureyev in the new biopic The White Crow. Born in Ukraine, he grew up speaking both Ukrainian and Russian. His career as a solo dancer began at the Tatar State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre in Kazan, 500 miles east of Moscow.

Rudolf Nureyev "became a monster of selfishness", says screenplay writer David Hare

He's danced big roles in classic ballets such as Coppelia, Giselle and La Bayadere.

"I always knew about Rudolf Nureyev but I had only seen short pieces of him dancing. To be honest I think the first thing I saw on video was him… with a pig?"

For a moment Ivenko hesitates, as though this might be something he's fantasised. But the scenes of Nureyev on The Muppet Show in 1977 have been watched millions of times online.

Until he was cast in The White Crow, Ivenko's English was almost non-existent. "So I had to learn - and also how to act. When you dance it's a type of acting but with your body - your mouth stays shut. I realised that for Rudolf suddenly to defect, at my age, to another culture and another language was a massive shock for him."

The film's screenplay is by David Hare, known as a widely produced playwright and for writing the series Collateral seen on BBC Two last year. He says the original idea for the new film came from producer Gaby Tana.

Oleg Ivenko says he believes Nureyev helped him to perform in The White Crow

"Gaby had read Julie Kavanagh's biography of Nureyev and she took it to Ralph Fiennes as a project. She told him the first six chapters were a fantastic movie - basically the events in Paris and what made Nureyev refuse to return home.

"They approached me and at first I saw the story just as the defection itself and what happens immediately before. Those are the thriller elements and were great fun to write. Someone told me those sequences in Paris reminded them of Hitchcock's North by Northwest - which I took as a huge compliment.

"But it was Ralph who then said the audience will need to understand his childhood and apprenticeship because that's what shaped him. Nureyev said he was playing princes on stage but he'd never been a prince in life: when he defected I'm sure he'd panicked and feared being sent back to Russia to be nobody again."

As a student Hare happened to meet the dancer after Nureyev came to Britain.

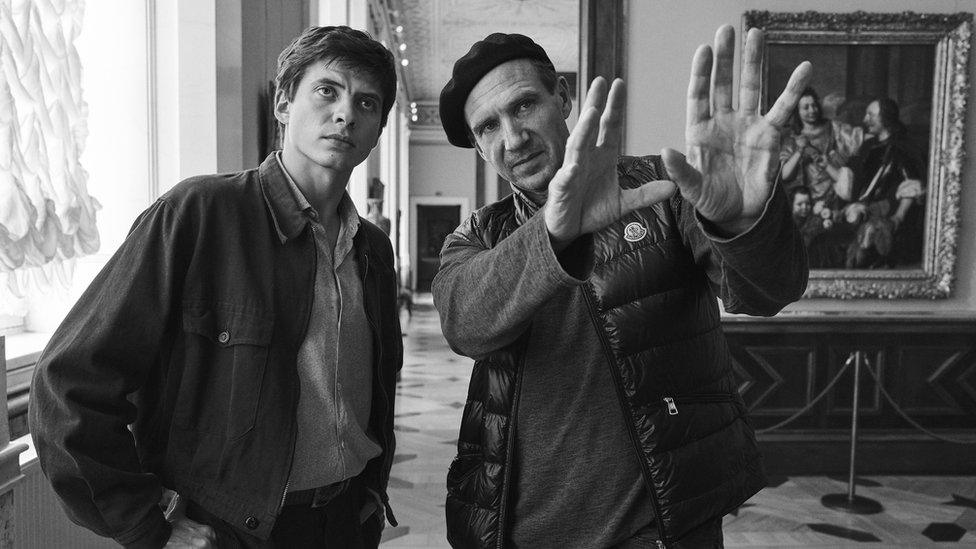

Ralph Fiennes directs Oleg Ivenko in The White Crow

A friend had a Russian mother and the family had invited Nureyev to stay. "I remember absolutely everything had to be arranged for Rudolf's benefit - was he warm and comfortable? How was his chair? Did he have enough to eat and drink?

"But he always assumed he'd just be the most talked-about person in the room and that meant he became a monster of selfishness. But the truth is he always was the most talked-about person. I did a lot of my own research with people who knew him: everyone had a story of the moment when you simply couldn't believe how badly he was behaving.

"The heart of it was that Nureyev knew he'd come from being a peasant. And because he thought he was a peasant he resented it when he thought people looked down on him."

Ivenko is a reasonable physical match for Nureyev. But did he also need to dance like him for the camera? "It's all about how you feel inside. If you go to the stage and you feel like Oleg Ivenko then that's how you will dance. When I was preparing for a take I talked with him, inside. I'd say come on Rudy I need you now - wake up. I think he helped me."

Ralph Fiennes (left) also plays ballet master Alexander Pushkin in The White Crow

Ivenko says Nureyev had a particular way of dancing. "Sometimes he was like a big cat, moving slowly. If you look at him on film, or listen to people who saw him, there was definitely something animal and sensual."

The dance sequences in The White Crow are expertly crafted but they make up only part of the film. So what opinion did Ivenko form of the man he was playing, aside from his undeniable skills on the stage?

"Sometimes I think he was a nice guy - but other times he was ruthless. But I respect him and I can see why he did certain things. I think he hid his feelings and always made sure he seemed a strong person. He could appear arrogant but inside he was like a baby left alone.

"For years Rudolf was going to a party every night or enjoying himself in gay clubs. But he had nobody just to sit with and to be together with."

The White Crow opens across the UK on 22 March.

Follow us on Facebook, external, on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external, or on Instagram at bbcnewsents, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published18 March 2019

- Published13 March 2019

- Published30 September 2018