Louis Theroux: 'I needed to give more of myself away'

- Published

There's not much Louis Theroux hasn't experienced of humanity. In more than 25 years of documentary making, he's moved in multiple worlds including those of neo-Nazis, Scientologists, pornography stars, those living with dementia - and Jimmy Savile.

While his approach has altered over the years, from comic gonzo to sober inquisitor, Theroux's ability to extract uncomfortable truths without confrontation has not.

Yet, the one person we don't get to know is Theroux himself. The questions are simple. The expression inscrutable. Only his eyebrows sometimes go rogue. In other words, he gives his interviewee space to show who they are.

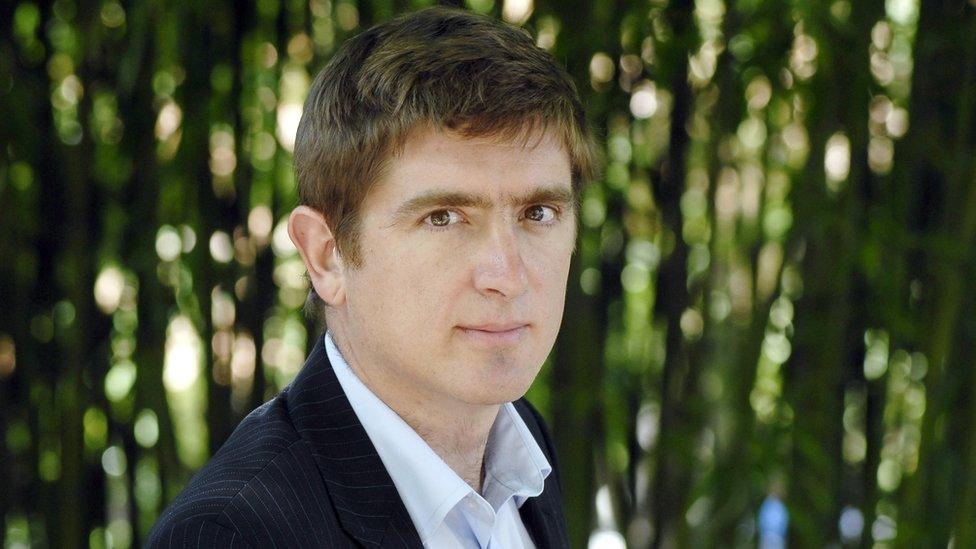

Louis Theroux is married to Nancy Strang

Epithets from "faux-naive", "impenetrable" and "wacky" have been employed in an attempt to define him. Theroux says he can, up to point, understand why.

"I plead guilty to, back in the day of Weird Weekends and When Louis Met, sometimes being a 'wacky' satirist, finding fringe people in marginal, wrongheaded or poisoned lifestyles and having fun with them, making them look a bit silly," he says.

"Now I cover stories I'm interested in, funny or not.

"We used to say, 'Where are the laughs?' as a way of eliminating a subject. But it's not about being Jeremy Paxman or David Frost, but being engaging, exciting and interesting and being the best me I can."

As Theroux edges towards 50, his latest project - a memoir - could help unmask the "real" him.

In Gotta Get Theroux This, he turns the focus inwards, to the workings of his TV world and his complicated mind. The title's pun comes from the ironic "cult of Louis" that spawned a range of Theroux-themed merchandise. Theroux wanted to "repurpose the meme, which never struck me as really that funny. Any pun on my name, I've heard a million times".

Paul Theroux became famous in the 1970s with his travelogue The Great Railway Bazaar

"But a theme of the book is getting through things, so I focused on challenges, things I found difficult: professional failures and worries, feeling I'm not up to it, I'm in over my head."

Theroux goes into forensic detail as he takes us through his childhood, into adulthood and becoming an alumnus of Michael Moore, to the present day. As for his personal life, it's been a rollercoaster of anxiety, self-doubt and emotional detachment. (There's also been a lot of pot smoking.)

"I take my work arguably too seriously. I neglected my personal life to focus on achieving some sort of professional success. The price of my lack of emotional nous was paid by those nearest and dearest to me."

He's had to learn to overcome the commitment issues which contributed to his first marriage's breakdown and almost broke his second to Nancy Strang, mother to his three boys. Given the commitment he's now asking of readers, he felt it necessary to be as open as possible.

Marcel Theroux is also a documentary maker and writer

"I owed them something that connects in a deeper way. I needed to be honest and to give more of myself away... feel kind of naked, in a surprising, maybe a shocking way."

Theroux talks about being "socially awkward" and not feeling right in his skin. It started young: aged five or six, he was already contemplating his death.

There is still room for Theroux to make documentaries with a lighter tone such as Love Without Limits

His father is the American writer Paul Theroux. His mother was a BBC World Service producer. Though loving, their parenting was hands off, leaving Louis and older brother Marcel (also a documentary maker and writer) with au pairs. Paul was also a philanderer. The couple divorced in 1993.

The young Louis, felt "freakish" and had few friends. He was fascinated with the macabre and taboo, and worked and worried himself to "emotional exhaustion" at his private school. Academic success was a pacifier when the rest of life felt out of control. He went on to read history at Oxford.

Theroux says his early resentment of his parents has mellowed but adds, "I'm very much the person I was as a child."

"For me, childhood is the most difficult passage of life. You feel imprisoned, enclosed within the choices made by other people. That can feel overwhelming."

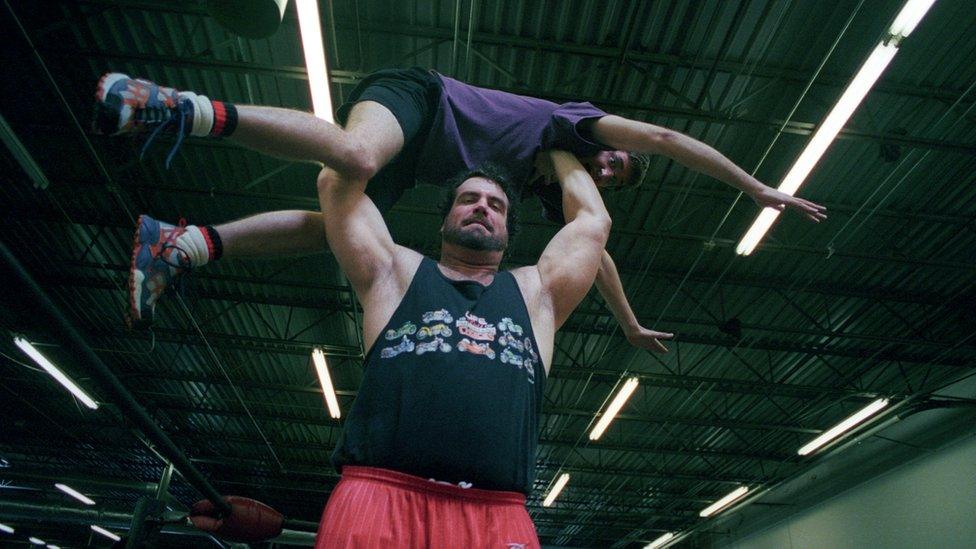

Weird Weekends saw Theroux come up against professional wrestlers

Needing distance, Theroux went to America after graduation (he's lived there on and off for several years). There, he was hired by the influential documentary maker Michael Moore - the man who would shape his future.

Fronting segments on Moore's satirical TV Nation, the naïf Theroux delved into the lives of off-the-wall characters and learned the naturalistic tricks of his trade.

"I can't imagine where I would be today were it not for that fateful day when Michael hired me and later told me to get on a plane and interview apocalyptic Christians. I felt completely out of my depth. But he had faith in me at a time when I didn't have faith in myself. I'd never considered being a TV correspondent. I've made sure I thanked him."

His subsequent move to the BBC and Weird Weekends, again set in the US, gave Theroux more doubts.

"I had enough American in me to be concerned that we might be making one of those 'let's make fun of Americans' type programmes."

When Louis Met... the Hamiltons he unwittingly experienced the full glare of being in the limelight

Weird Weekends became the vehicle by which Theroux was introduced to the British public. His "going native" rapport-building approach told a truer story than hard-nosed interrogation and won him an army of fans. The pay-off for Theroux was escapism: "When you're on location with people who think the heavens are going to rain down fire, the fact that you haven't renewed your car's tax disc doesn't seem so preoccupying."

However fame and success have sometimes divided Theroux. Even when winning awards, he's been torn between pride and feeling unworthy.

The limelight first blindsided him in the When Louis Met celebrity interview strand. The episode with UK politician Neil Hamilton and wife Christine saw him caught in the media commotion surrounding allegations of rape made against them (later discredited).

"I got into TV almost as a way of becoming invisible, in worlds where I was immersed in something remote from my daily concerns. But then I became the subject of tabloids and news reports. It wasn't comfortable," says Theroux.

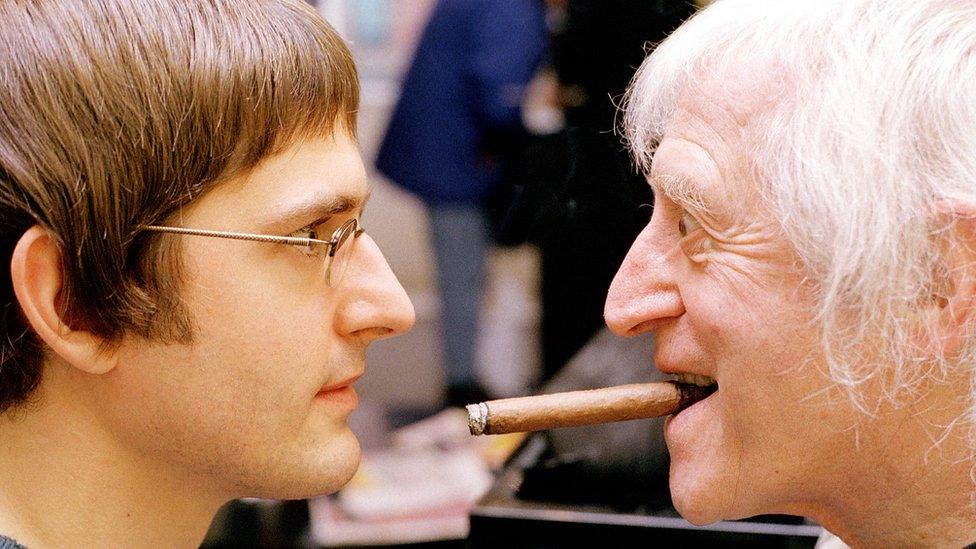

Louis Theroux has struggled with his feelings followng the revelations about Jimmy Savile

But it's the first show he made with Jimmy Savile in 2000 that left an indelible mark. Unsurprising, given what we know now. At the time Theroux could only say he felt Savile was "really odd, like someone with something to hide". The two struck up a kind of friendship, so the revelations about Savile's serial sexual abuse hit hard.

"I was stressed and upset and had a level of guilt, as part of me resisted believing," says Theroux. "I've come to the conclusion it was an understandable human response. The extent of his offending was so broad, it took a while to get your head around it."

He revisited the story in 2016, concentrating on Savile's victims. Personally, he hoped it might "exorcise" the ghosts still haunting him.

Louis Theroux looked into the world of mothers who have their new-born babies adopted in 2018's Take My Baby

"His victims have changed the landscape in the UK and how we think about historic sexual abuse or predatory behaviour by powerful people," says Theroux. "But what also came across clearly is the way some victims don't always immediately recognise it."

The seriousness of the programme was illustrative of the shift in tone of Theroux's documentaries over the last decade. Mental illness, adoption, and rape on campus are among the issues he's covered. The consistency lies in Theroux's human touch. The film-maker says he hopes to be remembered for "showing human nature in an honest way that connects with people for years to come".

His view of humanity now is "we are who we are".

"That can be really positive, altruistic, self-sacrificing and sometimes really bonkers". As for his attitude towards himself, he says: "I'm at peace with not being at peace."

Follow us on Facebook, external, or on Twitter @BBCNewsEnts, external. If you have a story suggestion email entertainment.news@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published1 October 2016

- Published3 November 2015

- Published21 March 2014

- Published20 March 2015