Still Undead: Will Gompertz reviews the Bauhaus show in Nottingham ★★★★★

- Published

Happy birthday Nottingham Contemporary!

The Caruso St John-designed art gallery situated near the city's old lace-making district is celebrating its 10th anniversary: a first decade in which it has mounted in excess of 50 exhibitions and welcomed more than two million visitors. Impressive stuff. Especially when you consider its approach to putting on shows.

This is an institution which doesn't sugar the art pill.

Its exhibitions tend to be as dry as dust, stripped to their bare essentials without any of the populist added extras beloved by wealthier museums and galleries. It wears its academic heart on its hipster sleeve, trusting visitors to share in its spirit of intellectual enquiry (exhibitions are free), with the promise of delicious post-show cake in the cafe (£5.95 for a coffee with a slice of brownie).

It's a winning formula.

Bauhausian, you might say.

At least you might if you had seen the gallery's latest show, Still Undead: Popular Culture in Britain Beyond the Bauhaus.

Bauhaus School in Dessau, designed by architect Walter Gropius in 1926

The exhibition marks the centenary of the now defunct German art school, which started life in 1919 in Weimar before relocating to Dessau in 1925. In the 14 years of its existence (Hitler shut it down in 1933) the now legendary institution played a central role in shaping the prevailing modernist aesthetics of the 20th Century.

The teaching staff boasted some incredible artists, including Wassily Kandinsky, Anni Albers, Josef Albers, and Paul Klee. The architect and designer Marcel Breuer studied and taught there, during which time he pioneered the use of tubular steel in furniture design, resulting in the iconic Model B3 chair now found in office lobbies the world over.

Wassily Chair, B3, was designed by Marcel Breuer at the Bauhaus School in 1925-26, but is ubiquitous today

The range of designs, art and ideas emanating from the Bauhaus was incredible.

Many were beautiful, such as Joost Schmidt's poster for the 1923 Bauhaus Exhibition, and Marianne Brandt's Coffee and Tea Set (1924).

Almost all were worthy of your time and attention. To see them laid out in an exhibition would be terrific.

Poster of the Bauhaus exhibition in Weimar in 1923 by Joost Schmidt

But you won't be finding any of them in the Nottingham Contemporary exhibition. It's not how they roll in this neck of the woods.

It'd be too obvious.

Instead, the curators have served up a very different but utterly compelling show, which feels a little esoteric at first but reveals itself to be a timely and important provocation.

It focuses on the experimental nature of the Bauhaus and how new philosophies about teaching and technology developed on its campuses in the 1920s and '30s affected post-War culture in Britain.

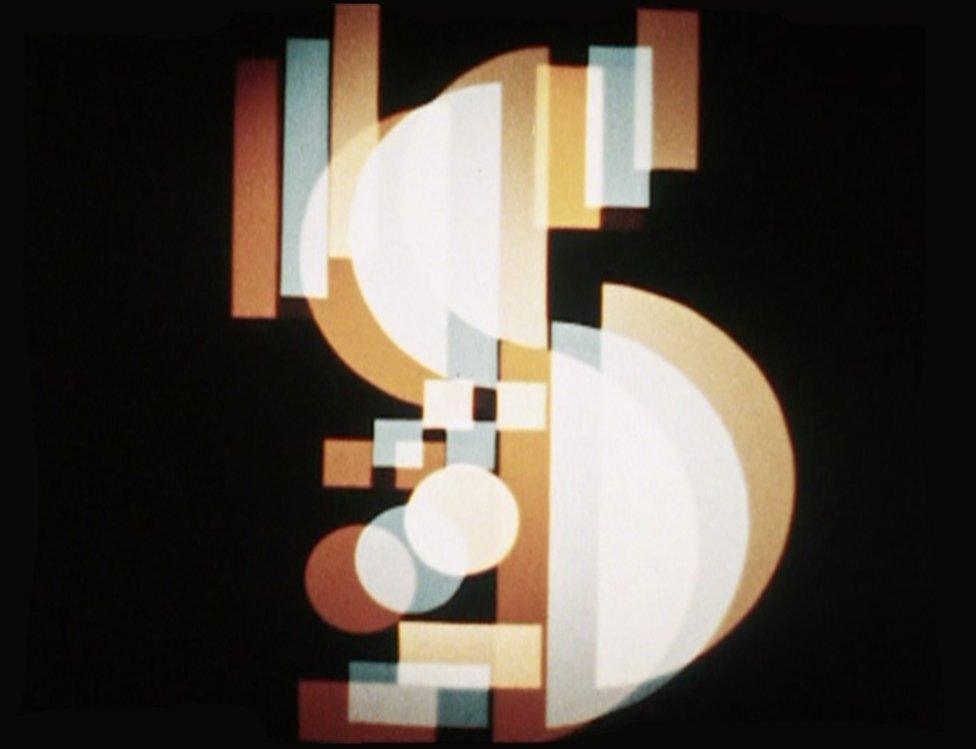

The exhibition starts with a large hanging screen showing a film of Kurt Schwerdtfeger's 1922 Reflektorische Farblichtspiele (Reflecting Colour-Light Games): a play of sorts, with a Heath Robinson-like invention acting as the set.

The contraption was made by Schwerdtfeger when a student at the Bauhaus for its Lantern Festival. It consisted of a large handmade, cube-shaped, apparatus containing lamps, in front of which performers would move cut-out shapes to create interconnecting geometric shadows on the surface of a screen accompanied by music.

Reflektorische Farblichtspiele, 1966, 16mm film transfer to digital, sound, 17 minutes 24 seconds, by Kurt Schwerdtfeger

The images look a bit like a pop video for Kraftwerk directed by a Russian constructivist on acid (it was first performed at a party hosted by Kandinsky).

It's good.

And significant, as a reference point for both the development of avant-garde filmmaking and performance art.

Behind it hangs another screen also presenting a film of a revered experimental work. It is called Light-Play: Black, White, Grey (1933) by the Hungarian artist and Bauhaus master László Moholy-Nagy.

Light-Play: Black, White, Grey (1933) by the Hungarian artist László Moholy-Nagy

It shows the interplay of shapes created by shining light through a rotating (kinetic) metal sculpture he called Light-Prop Lightspace Modulator.

These aren't "easy" works of art.

In fact, they weren't really conceived as works of art at all.

They were artistic investigations into a central idea of the Bauhaus, which founder Walter Gropius referred to as "an alliance of the arts": a desire to unite art, design, technology, and life.

Walter Gropius, regarded as one of the fathers of modern architecture, is standing in front of a house designed by him in 1927

Moholy-Nagy believed such a synthesis was possible, enlightening even, and was searching for a way of articulating the vision. If such a concept appeared vital at the time, it seems even or pressing now.

But which art school or institution is currently investigating such bold and ambitious ideas?

Several were for a while. In Germany and America and Britain.

After the Bauhaus closed, Moholy-Nagy, Gropius and many other students and masters came to the UK to look for work and share their knowledge. There's a slow but captivating film by Moholy-Nagy studying the modernist architecture of Whipsnade and London zoos.

At this point in the exhibition the emphasis shifts from Bauhaus emigres to the influence they had on Britain. Mary Quant ("the Bauhaus ideal is about making modern design accessible"), Terence Conran, and Vidal Sassoon all feature. As does the artist Richard Hamilton who is represented by a handful of works including his excellent painting, Trainsition IIII (1954).

Vidal Sassoon: Bauhaus (Spirals), 1986, by Robyn Beeche (make-up by Phyllis Cohen)

Trainsition IIII (1954) by Richard Hamilton

Hamilton was one of several advocates of a foundation course called Basic Design, based on the Vorkurs preliminary course at the Bauhaus, which encouraged intuition and experimentation. The results of Basic Design course are presented in the final room of the exhibition, which is dedicated to work connected to Leeds Polytechnic in the 1970s and 80s: a place the artist Patrick Heron proclaimed to be "the most influential art school in Europe since the Bauhaus."

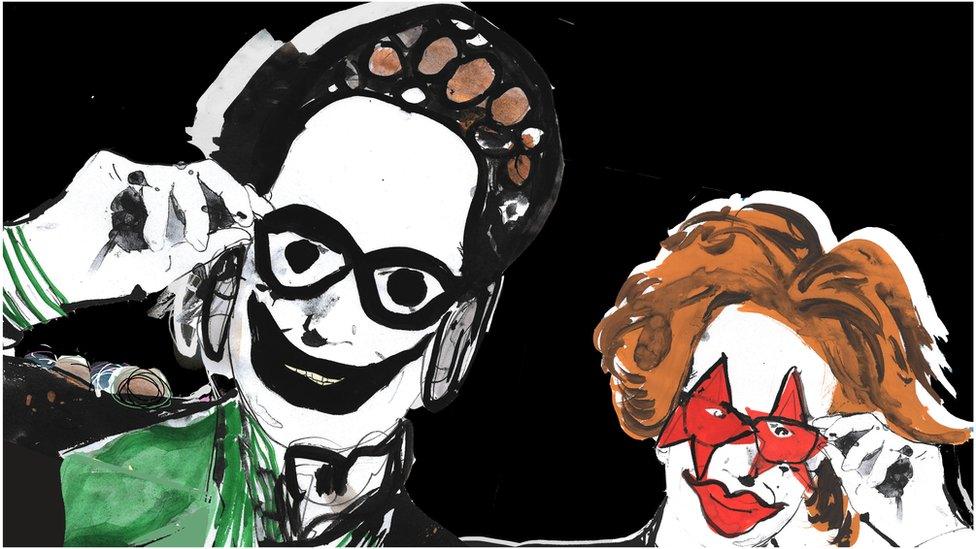

Frankly, I'm not sure time has borne this out, but it still makes for a rousing finale: a black-walled, double-height gallery displaying - among many objects and films - a wonderfully eccentric Charles Atlas video called Mrs. Peanut Visits New York (1992), and an unforgettable series of photographs featuring performance artist Leigh Bowery by Robyn Beeche called 7th Alternative Miss World…(1986-7).

7th Alternative Miss World contestant, 1986. Leigh Bowery and assistant the late Jill; Swimwear, by Robyn Beeche

This is to barely scratch the surface of an encyclopaedic show that has resisted presenting the typical Bauhaus collection and focused more on its spirit: its openness to ideas, its willingness to challenge convention; to seek to unite art, technology, life, and science: to re-think the purpose of education, the contents of the curriculum, and the student experience.

This was an institution that urgently wanted to make a difference; to positively impact on the lives of those on and beyond its campus.

It leaves you thinking that is what we need now: a revolutionary approach to art and education. There's no reason it shouldn't start here in the UK. After all, that's where the seeds of the original Bauhaus were sown.

But that's another story…

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external