Friendship: Will Gompertz reviews the work by US artist Agnes Martin ★★★★★

- Published

I was looking at an online image of an abstract painting called Friendship by the late American artist Agnes Martin (1912 - 2004) when my son lent over my shoulder to take a look.

"What's it made out of? he asked

"Gold leaf" I said.

"When was it painted?"

"1963."

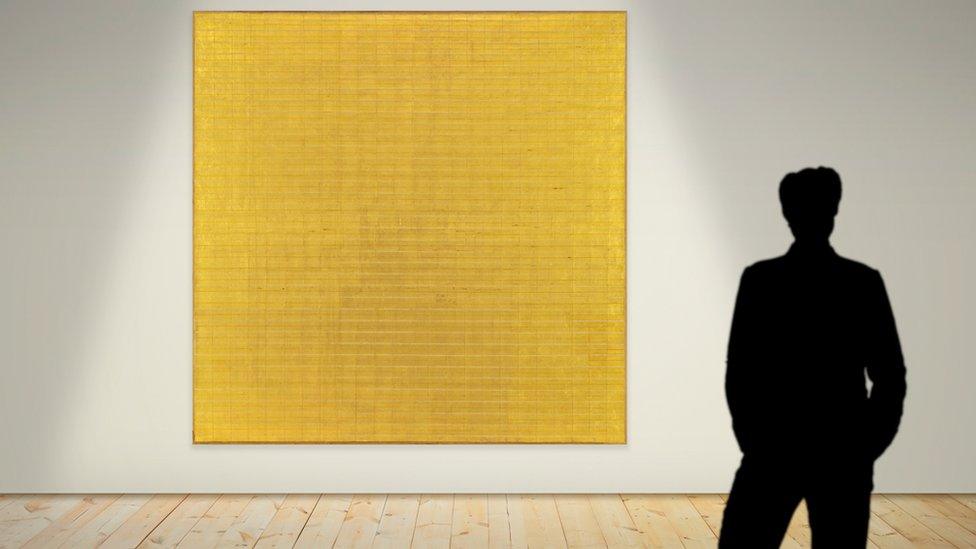

"How big is it?"

"Over six-foot square. Isn't it great!"

"Probably better in the flesh" he said, and wandered off.

He was unimpressed, and I don't blame him.

At first glance, especially on a computer screen where all sense of scale and materiality are lost, the painting looks flat and lifeless. But give it half a chance, zoom in and out a bit, external, and you will discover a modern masterpiece that offers a much-needed balm for our troubled times.

Friendship is the product of decades of trial and error that saw Agnes Martin go from figurative painting to Rothko-like floating colour fields via the biomorphic surrealism of Joan Miró.

In the early years of her career, Martin was influenced by the biomorphic surrealism of Miró (Harlequin's Carnival, 1924-25)

Martin was then drawn to Mark Rothko's style (Red, Orange, Orange on Red, 1962)

Almost all of this early work ended up on a bonfire.

Finally, in her mid-40s, which was in the late '50s, she found a style of painting and a subject - positive feelings - that would sustain her for the rest of her life.

The result was a remarkable, unique body of work that brings our unconscious into plain sight.

We know what companionship is, we know what it feels like, but what does the sensation of mutual affection actually look like? It's not something we spend much time thinking about, unlike Agnes Martin who contemplated the manifestation of our inner sensations for five decades.

Friendship (1963) is an early foray into her quest to make our feelings visible. At the time she was living in the semi-derelict lofts on the Coenties Slip near Wall Street in New York; hanging out with the Abstract Expressionist crowd and thinking about the paintings made by her friend Elsworth Kelly, which consisted of large blocks of colour.

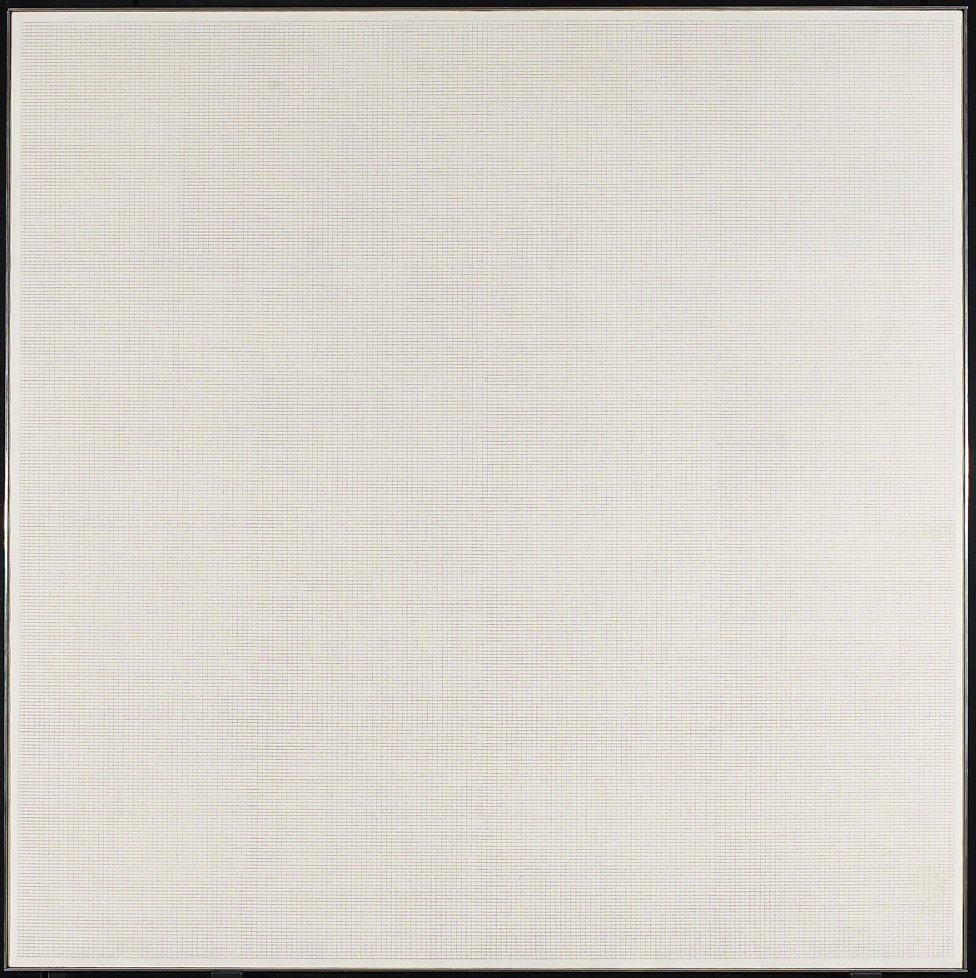

Friendship (Gold leaf and oil on canvas, 6' 3" x 6' 3") was painted in 1963 by Agnes Martin, who once wrote "Without awareness of beauty, innocence and happiness, one cannot make works of art"

But colour alone wasn't enough for her.

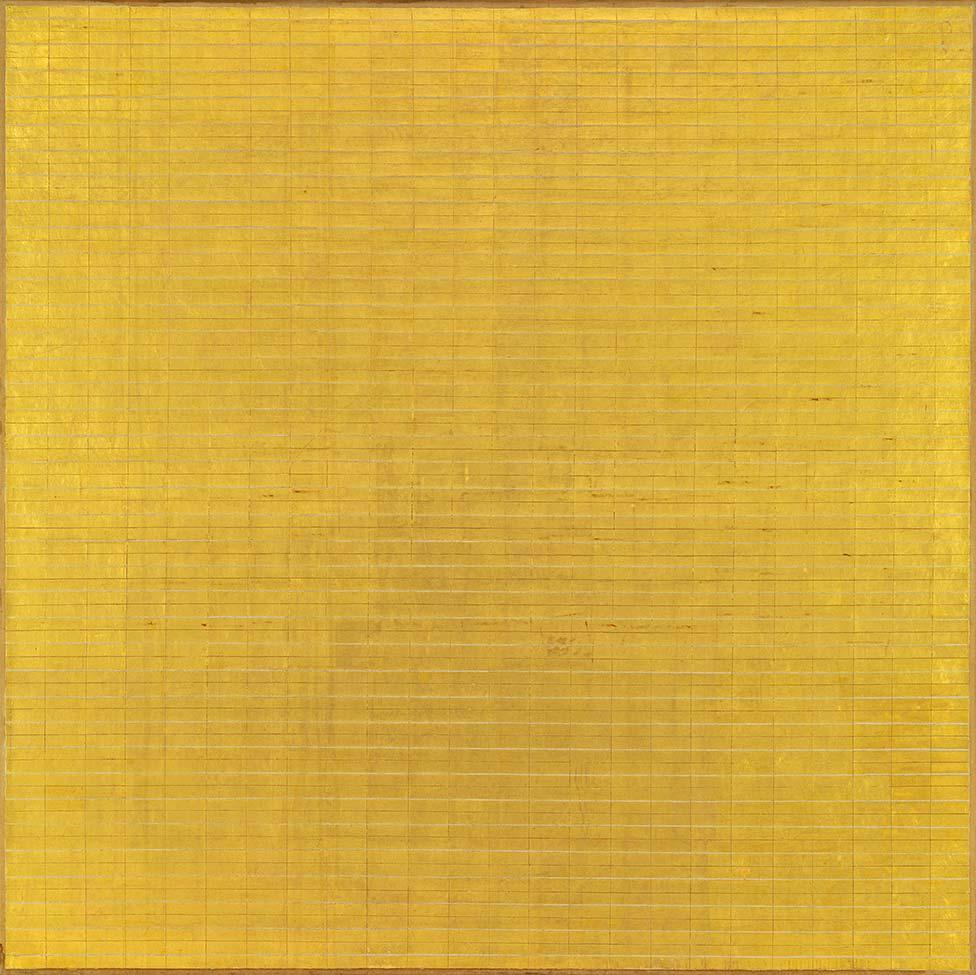

There had to be an order to things, a formal structure through which the expressive nature of paint could be contained and communicated. Her solution to the problem was simple yet brilliant, as you can see with Friendship.

Having applied the gold leaf to the huge canvas she stood back and contemplated her next move. Rothko would probably have left well alone, as would Kelly. But Agnes knew her painting lacked depth. It was superficial.

She had to get under its skin to reveal its soul.

And so, she began to score the surface with a series of horizontal and vertical lines until the entire image appeared to have been made on a piece of giant graph-paper.

The effect was incredible.

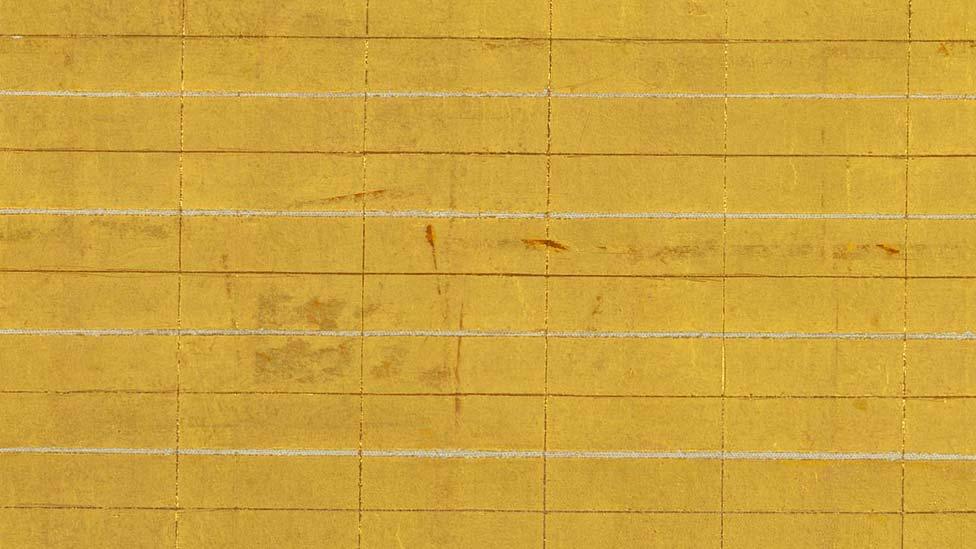

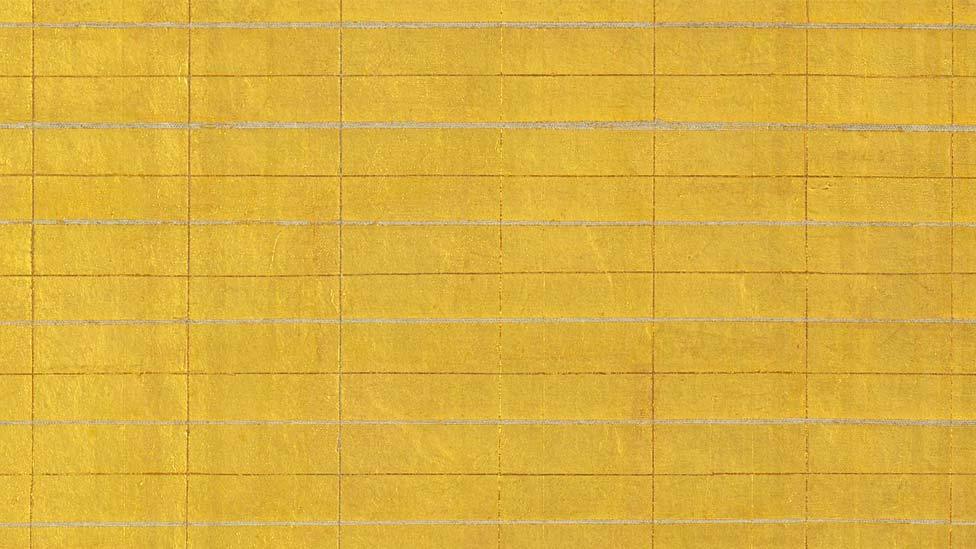

What had been a completely flat image the viewer perceived as a single, static unit, suddenly became a three-dimensional painting full of life and intrigue. Crucially, the geometric lines were hand-drawn by Agnes, not machine-made, which meant they were full of tiny human errors, giving the surface a jittery, vibrating quality that entices you to look closer. And when you do, you realise there's a red undercoat bleeding through the patchy golden surface.

A closer look at the painting reveals extraordinary detail with red coming through the golden work

It turns out Friendship is far from superficial. It has depth and breadth and intelligence. But, most of all, it has feeling.

It is an uplifting painting celebrating affinity, which Martin arouses and exposes with a joyous ebullience. This is what the feeling of friendship looks like: warm, rich, glowing, textured and imperfect.

The gold leaf was an anomaly for Martin who believed in humility and detested pride.

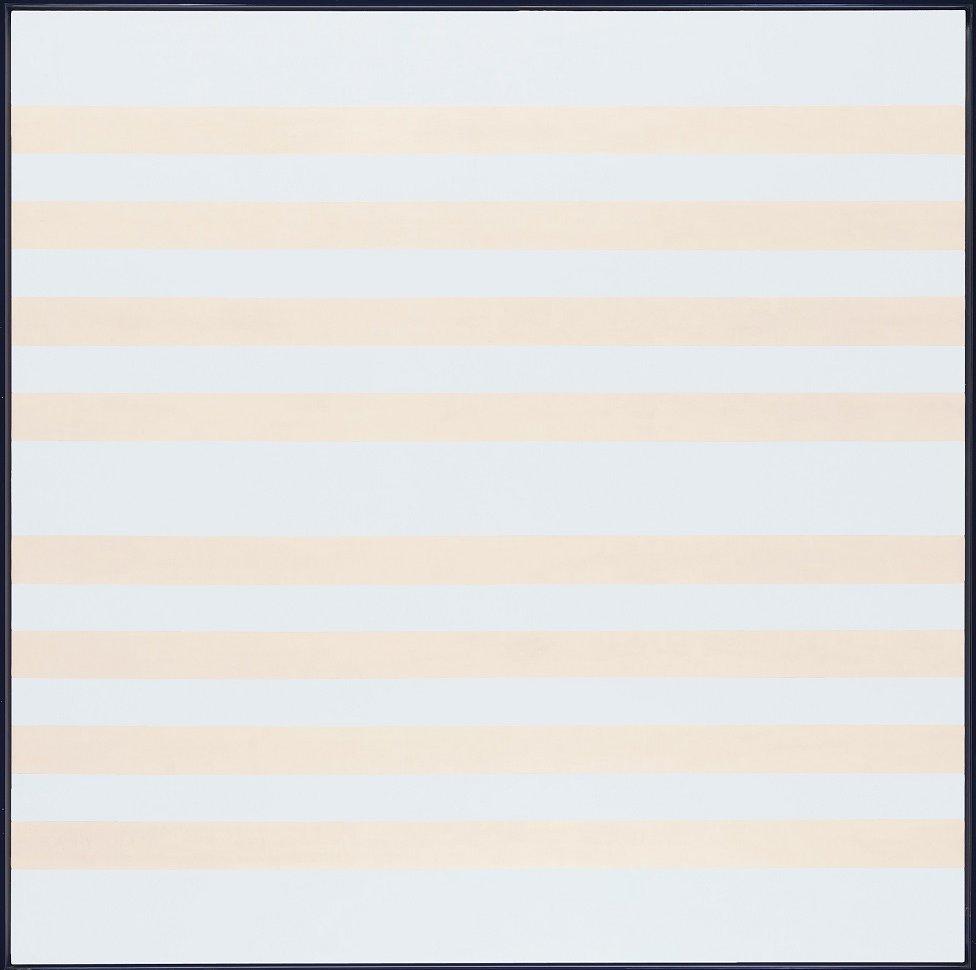

Her palette would quickly evolve into more muted colours - greys, browns and blacks - before settling on pastel shades of blue, pink, and off-white. But her subject remained the same: emotions such as happiness, love, and innocence. As did her dedication to geometric structures and what would come to be known as the Agnes Martin "grid"'.

The Agnes Martin "Grid" became the artist's hallmark

Take any one of her hundreds of pictures and you will see the same effect, the simultaneous play between the faultless and the faulty, certainty and uncertainty. It's there in an early work like The Rose (1964) and in a later piece such as Loving Love (2000). It is what gives her paintings their personality, their appeal. Our eyes and minds are intrigued by the constant play between perception (perfect) and reality (imperfect), one resolving the other like a musical chord.

The Rose (1964) by Martin, who said "the beauty is not in the rose, the beauty is in your mind"

Loving Love was painted by Agnes Martin in 2000, four years before her death

There is little doubt that her fragile mental state informed her paintings. She was seeking tranquillity and order among chaos; to create images of beauty and happiness to dispel dark thoughts. She did so with a form of meditation, the purpose of which was to banish the act of thinking entirely. Her mind, once cleared, waited patiently in a semi-trance for an image to appear in her a head - an "inspiration" - which would show her the next painting to make. This is not as bizarre as it sounds, you hear artists of all types talking about a similar process to overcome "writer's block" or waiting for the "creative spark". Novelists speak of a book "writing itself" with them merely the conduits.

The way she achieved a state in which she could receive an inspiration, was to be completely alone with a giant Do Not Disturb sign hanging above her head for all to see from miles around.

That's perfectly normal. What makes her situation different, is the extremes to which she took the notion of seclusion.

Agnes Martin didn't so much get by without mod cons, but without any cons whatsoever. She lived alone on an isolated mesa in New Mexico with no running water or mains electricity. Admittedly, she did own a bath. Not tucked away in a cosy corner of her adobe shack, mind you, but outside in the yard. She would fill it with buckets of cold water at 10am and hope that by 4pm, shortly before the sun went down, it would be warm enough to bathe in.

It's been said that neighbours who popped round offering cake and cookies were welcomed with the business end of her gun. And paintings she made that failed to live up to her exacting standards were lacerated and destroyed with a knife, accounting for about 95% of her life's work.

If inspiration didn't call she wouldn't paint that day, week, or month. On one occasion, after a very successful show of her geometric abstract art in the 1960s, she downed tools completely. For seven years.

The photographer Michele Mattei captured the essence of Agnes Martin in her studio in Taos, New Mexico a few months before her death, and described the artist as "a woman of few words, focused on her own private thoughts"

The story goes that she once told a man who thought they were pals that she didn't have any friends, and he was one of them (in truth she did have friends, and enjoyed giving public lectures). If you were to form an instant opinion of this reclusive artist who spent forty years of her life drawing grids on 6ft x 6ft canvases, the inclination would be to conclude she was a dyed-in-the-wool oddball.

There are, however, two explanations for her seemingly erratic behaviour. The first being her Zen-like approach to making art, which required long periods alone, and, secondly, she had schizophrenia. Whether they are interconnected matters not, the point is Agnes Martin wasn't an oddball.

She was deeply spiritual, highly intelligent, sensitive, focussed, talented, and dedicated artist.

Solitude was her source material just as a landscape painter draws from nature and a portraitist from a sitter. She might have come across a tad ferocious if caught at the wrong time, but that's not particularly unusual.

The fact is she was devoted to making paintings full of inner love to go out into the world and cheer us up when we really needed it. Like now.

There's a lot to be said for Friendship.

Recent reviews by Will Gompertz

Follow Will Gompertz on Twitter, external